Fan Surplus, HYBE, and the Science of Fandom

Why the Future of Media is Selling More to Fewer

The subtitle of this post is a nod to The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More, by Chris Anderson. Written more than 20 years ago, it was ahead of its time. A lot of consumption has shifted into the tail. But for media companies that want to grow, the future of media is selling more to fewer.

I recently wrote a post called What if All Media is Marketing? The idea is that if GenAI collapses the cost to make content, content pricing and profits will also collapse, so the only way to make money will be to sell complements—products and services adjacent to the content itself. Content goes from primary profit center to top-of-funnel.1

After that post, the question I got back most often was: “OK, but how do you develop successful complements?” As I explain in this follow up, the critical lens to use, and the question that every media company should be asking, is: what would my most dedicated fans pay more for? Said differently, the bottom of a funnel is smaller than the top. Traditional media companies need to shift their focus from reaching the many to superserving the few(er).

Tl;dr:

Let’s coin the term fan surplus. If consumer surplus is the difference between consumers’ willingness-to-pay and the market price, then fan surplus is fans’ excess willingness to engage more deeply, more frequently, and across more dimensions with the objects of their fandom.

The media industry’s biggest necessity and opportunity is to capture fan surplus.

Media derives revenue by monetizing consumer attention and engagement. The bad news is that attention is finite and no longer growing. As GenAI advances, increasing time spent becomes a zero-sum game that traditional media companies can’t win. The good news is that engagement is unbounded—especially from the most ardent fans.

Historically, media companies had limited tools to capture fan surplus. Pre-internet, distribution was one-to-many, with no way to tailor products or accurately measure consumption and no knowledge of its consumers. An artifact is that most media products are still one-size-fits-all, regardless of degree of engagement: one CPM, one price for an album or game, one price for a movie ticket. Many media companies also still cling to a reach mentality.

Today, media companies have the tools. They can create effectively infinite versions of media products; gather granular user data; and monetize through built-in payment rails. GenAI will enhance this toolset.

To understand what it means to systematize fandom in practice, look to South Korean music label HYBE. It builds groups from the ground up to maximize fandom; owns its own fan communications, commerce, and concert platform (Weverse); and uses the associated data to inform product development, marketing, release schedules, etc. As a result, it derives a much higher proportion of its revenue from “fandom” than peers.

Today, most media companies manage fandom, but they don’t foster it, cultivate it, or, for the most part, monetize it. In the future, they’ll have to.

What is Fan Surplus?

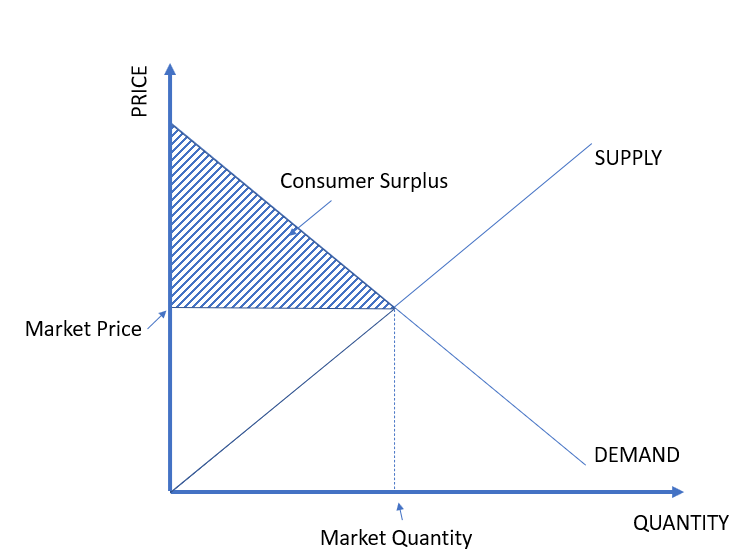

Consumer surplus is the term economists use to describe the excess value that accrues to the consumers that are willing to pay more than the market price. Consider Figure 1. Other than edge cases where demand is entirely inelastic, demand curves slope down, like this one. The market-clearing price occurs where supply meets demand. Since the demand curve slopes down, that means all the demand to the left of the market price represents consumers whose willingness-to-pay (WTP) was higher.

Let’s take demand for lattes and assume that the market clearing price is $5. There may be some who would pay $12, some $10, some $7, and so on. The difference between their WTP and what they actually pay is consumer surplus.

Figure 1. Consumer Surplus is What Accrues to All the People Who Would’ve Spent More

Source: Every microeconomics textbook ever.

“Fan surplus” is excess willingness of fans to engage more deeply, more frequently, and across more dimensions with their favorite characters, artists, teams, or stories.

Strictly speaking, consumer surplus arises because some people would pay more than others for the same thing. I’ll coin a related concept, which I’ll call fan surplus: excess willingness (or eagerness) of fans to engage more deeply, more frequently, and across more dimensions with their favorite characters, artists, creators, teams, or stories.

Extracting fan surplus is the industry’s biggest necessity and opportunity.

The media industry’s greatest necessity and opportunity is to capture this surplus by giving the most ardent fans more of what they want. It’s a necessity because media attention is no longer growing; it’s an opportunity because fans are willing to engage, and pay, more.

Let’s discuss each.

The Attention Problem

Every time I give a presentation, I make the point that ultimately the media business is about monetizing consumer attention and engagement. When you think about it, this is not true for most businesses. The price you pay for a steak doesn’t reflect how many times you chew it and the cost of your car is not based on the length of your commute. In the case of media, however, the revenue a business generates is directly or indirectly correlated with the amount of time consumers spend (especially for advertising-supported businesses). So, the amount of available attention is a structural constraint on the size of the business. And the problem is that there isn’t a lot more attention to go around.

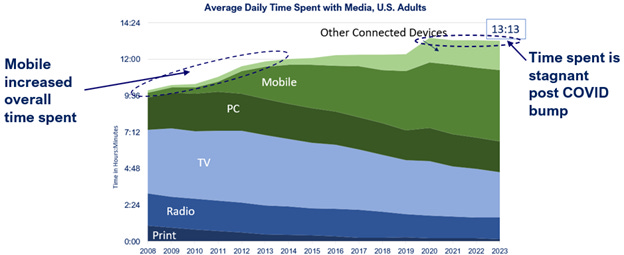

As shown in Figure 2, in the U.S., the average adult spends more than 75% of waking hours with media, which is probably pretty consistent with other advanced economies. Figure 3 shows a time series of time spent with media (albeit from a different source). Time spent grew with the advent of a major new form factor—mobile—then leveled off. Then it got a bump around COVID, but it has been stagnant since.

Figure 2. The Average U.S. Adult Spends 13 Hours Per Day With Media, >75% of Waking Time

Note: * Social video is included in Messaging and Social. Source: Activate.

Figure 3. Time Spent with Media is No Longer Growing in the U.S.

Source: eMarketer.

Is there a reason to be hopeful that time spent with media ever climbs meaningfully again? Perhaps. Maybe self-driving cars proliferate and free up commuting time for media consumption. Or maybe AI is so good at automating tasks that it increases leisure time. But both are a tough bet. It seems just as likely that new competitors for content consumption time arise, too. For instance, as the barriers to content creation fall, it’s possible that the biggest competitor for time spent consuming content will be time spent creating it.

It’s tough to bet that time spent with media will grow materially. As GenAI advances, increasing time spent becomes a zero-sum game that traditional media companies can’t win.

As GenAI continues to lower the barriers to entry, the competition for time will get ever more intense. Call it AI slop or brain rot or whatever pejorative you want. It will, almost undoubtedly, draw away some of consumers’ attention.

So, for traditional media companies, increasing time spent is a zero-sum game that they can’t win.

The Engagement Opportunity

If attention is no longer growing, what about engagement? There isn’t a consensus definition of engagement, but here’s a simple one: engagement is the depth, quality, and intensity of attention. And here’s the good news. While attention is finite and, as far as we know today, tapped out, engagement is unbounded.

The other good news is that consumers can have extraordinarily strong feelings for media products and artists, so engagement can be very deep, very high quality, and very intense.

The bad news: attention is finite. The good news: engagement is unbounded.

Fans Have a Very High Willingness to Pay

It is self-evident that people can get very fanatical about their favorite musical acts, movies, books, actors, or TV shows. We’ve all seen the iconic footage of hysterical screaming girls when The Beatles landed at JFK or appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show. If you’ve been to a Harry Styles concert or ComicCon or seen what happens when you cross Zack Snyder fans, you’ve experienced it personally. People go into debt to see Taylor Swift. They get tattoos of their favorite media properties. (And I won’t even bring up sports, which is on another level.) But it’s worth spending a moment to understand why this happens and why it matters.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Mediator to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.