Infinite Content: Chapter 4

Stagnation, Fragmentation and Deflation: The Cost of Free Distribution

This is the draft fourth chapter of my book, Infinite Content: AI, The Next Great Disruption of Media, and How to Navigate What’s Coming, due to be published by The MIT Press in 2026. The introductory chapter is available for free here. Subsequent draft chapters will be serialized for paid subscribers to The Mediator and can be found here.

It is perhaps cliched, but no less striking, how different were the early media experiences of the people reading this book. I will date myself with the following, but so be it. For some it may inspire nostalgia, for others it will be utterly unrecognizable.

When I grew up, there were three big TV networks, ABC, CBS and NBC, and a handful of local stations. We had a Zenith TV with a remote that would trigger a motor in the TV that physically moved the dial. The remote was heavy and made a satisfying ka-chunk sound when you changed it, although it could only go up or down one channel at a time. I remember how exciting it was when cable came to our neighborhood and the first set top we got. It had white push buttons on it, but otherwise looked a little like this:

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

I also recall huge cultural events, even if I didn’t understand them at the time. I had an original Woodstock poster on my wall (sadly, I have no idea where it went). That was a little before my time, but I still knew it meant something important. I remember being shooed off to sleep so my parents could watch the finale of the miniseries Roots (which still holds the record as the second highest-rated series finale in TV history). I also remember my mom watching David Frost interview Richard Nixon and not having the foggiest why anyone would find that interesting. I was wistful while watching the last episode of M*A*S*H in 1983, but CBS probably was not. It attracted 122 million viewers, the single highest-rated TV episode ever, and commanded ad rates higher than the Super Bowl that year.

It was around this time when Star Wars came out, in 1977. It’s hard to capture just how popular it was. People waited in line for hours to see it. It was #1 at the box office for 27 weeks. It played so long that some theaters needed replacement prints because they were wearing out. It was still playing in some theaters when the sequel, The Empire Strikes Back, came out in 1980.

When I was in 6th grade, one day my social studies teacher, Ms. Maldonado, informed the class that we would be required to memorize the 50 state capitals, news that sent the class into an apoplexy. She deftly changed the topic, then toward the end of class started to pepper us with questions about what was on TV that night, then the next, then the next, all of which we dutifully and accurately answered, shouting out answers in a competition to show who knew the schedule better. Then she went for the kill. “Well, since all of you seem to have no problem memorizing the entire TV schedule, you should have no problem with the 50 state capitals.”

Today, massive shared cultural experiences like Woodstock, Roots, M*A*S*H and Star Wars are vanishingly rare. Movies are in and out of theaters in weeks. And there is no TV schedule to speak of, certainly none that any 6th grader could cite.

Last chapter, I described how digitization and the internet fundamentally changed the substrate and architecture of media; how this resulted in changes at the systemic level; and how those systemic changes manifest themselves in the business today—or what I refer to as the tectonic trends in media.

The transition of media distribution from very costly to functionally free led directly to three tectonic trends in media today: stagnation of time spent, fragmentation of attention, and price deflation.

As I also described, the most important systemic change was that media distribution went from very costly to functionally free. The resulting lower barriers to entry enabled an explosion of content supply, leading directly to the three interrelated tectonic trends I discuss in this chapter: stagnation, fragmentation, and deflation. Each are a likely a harbinger of what’s to come as GenAI lowers the barriers to content creation too.

Stagnation

The concept of stagnation is straightforward. The business of media is monetizing attention and engagement. Attention is synonymous with time. As the volume of content increased over the last 10-15 years, time spent with media also increased. But there’s no longer much time to go around.

Stagnation of time spent with media imposes a structural constraint on growth.

As I described in Chapter 2, owing to the prevalence of advertising-supported models, the value of media is correlated with the amount of time consumers spend with it. The challenge for media is that there are only so many hours in the day and people already spend an awful lot of them using media products.

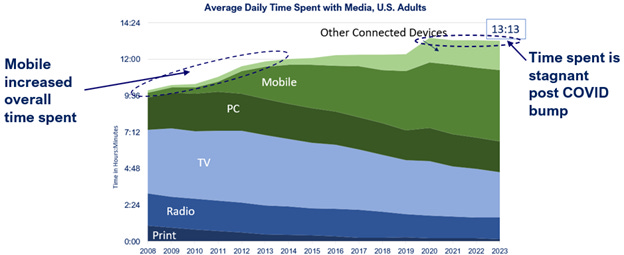

In Chapter 2, I showed that the average U.S. adult spends more than 75% of waking hours with media (Figure 5). It will be tough to grow much from this level. As shown in Figure 16, in the U.S., time spent with media grew around the advent of the smartphone, circa 2008, and experienced a COVID-related bump in 2020, but it has been stagnant since. Media usage is probably higher in the U.S. than many markets, owing to long commutes, but in light of high levels of mobile penetration globally, it’s probably not far off.

Figure 16. Time Spent with Media is No Longer Growing in the U.S.

Source: eMarketer.

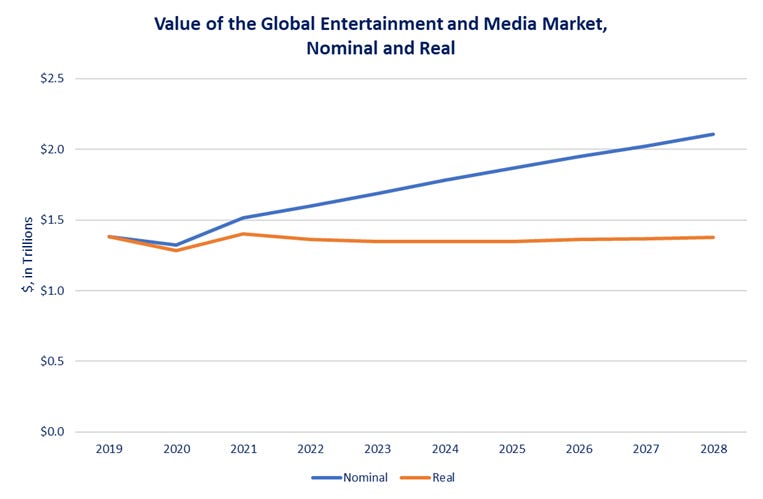

In general, this dependence on time and the difficulty increasing time spent from such high levels are likely to be a structural constraint on growth for the broader media and entertainment (M&E) sector. As shown in Figure 17, consulting firm PwC doesn’t expect M&E to grow on an inflation adjusted basis. And this includes all media—not just traditional media, like print, linear TV, and theatrical films, but also faster growing “new” media, like streaming, gaming, search, and social.

Figure 17. Globally, M&E Isn’t Growing on an Inflation Adjusted Basis

Note: Includes what PwC calls “Advertising” and “Consumer,” but excludes “Connectivity.” Source: PwC, Omdia, The Mediator analysis.

Fragmentation

The concept of media fragmentation is also straightforward enough. It refers to the dispersion of a finite amount of attention across an increasing number of media sources. It also isn’t new. Figure 18 charts the evolution of media technologies, starting with the Gutenberg printing press around 1440, and then on to newspapers, radio, film, TV, video games, the internet and so on. Each has redistributed the time people spend with media.

Today, it is palpably obvious in our daily lives that we get information and entertainment from a bewildering number of places, particularly when everyone seems so attached to their phones and it is often hard to remember where one saw or heard something. But like a lot of things that are obvious, it is possible to draw important insights by probing a little.

Two Types of Fragmentation

There are two main types of fragmentation:

Fragmentation between formats. Figure 18 shows something else too. As noted by the color coding, each of these technologies operates primarily within one of several formats: text, audio, video, interactive, and spatial. Occasionally, a new distribution technology introduces a new format. Recorded music was the first audio format; film was the first video format; video games introduced interactivity; VR devices pioneered spatial as a new format. The internet is the first truly format-agnostic distribution technology, because it can be used to deliver all other formats. (At some point, we will run out of senses, but perhaps there will eventually be olfactory, haptic, and even neural formats too.) To some degree, each format competes for time with other formats. (Emphasis on some, as I’ll explain below.)

Fragmentation within format. This occurs when the barriers to entry within a format fall, enabling new competitors for time within that format (more articles, songs, videos, games, etc.).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Mediator to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.