Infinite Content: Chapter 12

Where Value Flows Next—and Why Incumbents Aren't Necessarily Toast

This is the draft twelfth chapter of my book, Infinite Content: AI, The Next Great Disruption of Media, and How to Navigate What’s Coming, due to be published by The MIT Press in 2026. The introductory chapter is available for free here. Subsequent draft chapters will be serialized for paid subscribers to The Mediator and can be found here.

In mid-2008, I was working at Time Warner Corporate and was summoned to sit in on a meeting between two Time Warner divisions, Warner Bros. and HBO. Being part of the same company, you might think these sorts of meetings happened all the time, but they did not. (In the case of Time Warner, the word “divisions” had two meanings.) The topic at hand was whether (or not) to pursue an acquisition of Netflix.

The Warners camp, led by future Warner Bros. CEO Kevin Tsujihara, was in favor; the HBO camp, led by future HBO co-CEO Eric Kessler, was opposed. It would be fun to go back in time and be a fly on the wall for this debate, knowing what we know now. It’s also interesting to envision an alternative history in which Time Warner successfully acquired Netflix. Would Time Warner still be around today? Or would we have inadvertently smothered Netflix and another company would have emerged as the global streaming leader, like maybe Amazon or Apple? Who knows?

The reason I bring up this anecdote is not to dabble in counterfactuals, but to relay the one thing I remember clearly about that discussion: Tsujihara thought we could get it for $5 billion. Today, Netflix has a $400 billion market capitalization. That compares to $430 billion for Comcast, Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, Fox, and Paramount, combined. To quote Michael Scott from the U.S. version of The Office, “Well, well, well. How the turntables.”

At the heart of it, disruptive innovation theory describes how disruptive technologies reorder the economics of an ecosystem. Sometimes they create value, but they always redistribute it. GenAI has all the hallmarks of a disruptive innovation, because it will drive down the cost of content creation, which is a critical input in the media value chain, and lower entry barriers. Under any plausible scenario, that will be disruptive—and especially so under the “Infinite Content” scenario we discussed last chapter. Just as the internet did before it, it will reorder the economics of media. Billions, maybe trillions, of dollars are at stake.

Who stands to gain and who stands to lose?

There’s a superficially obvious answer to this question. The incumbents are screwed. Most media incumbents are still reeling from the internet and now another wave is about to hit. Value will continue to flow away from them toward top creatives/creators, disruptors, platforms, and consumers.

We could just end the chapter there, which would be mercifully short but not particularly useful. It may also be wrong. Disruption is a very powerful force, value is already flowing away from the incumbents, and the deck is surely stacked against them. But what happens next is not a fait accompli.

In this chapter, I’ll introduce a framework to help think through how GenAI will redistribute value in media. In disruption, value tends to flow away from incumbent value pools in four directions, what I call the 4Cs: toward Challengers (i.e., disruptors), Consumers, Complements, and Chokepoints. The key is the term “value pools.” Value doesn’t flow away from incumbents per se; it changes where and how value is created. Some complements and chokepoints are accessible for incumbents and, through the right steps, they can mitigate the effects of disruption or perhaps even benefit. It won’t be easy, but it is possible.

If you are trying to figure out the practical implications of GenAI for media and where to place bets, this is the most important chapter in the book.

Value, Value Chains, and Value Pools

Before we discuss how GenAI will redistribute value, we need to define a few things, including value itself.

Value

There is no consensus definition of value, since different stakeholders value different things. Here’s the definition we’ll use: value is the total economic surplus generated by a business activity. This includes both monetized surplus (which shows up as profit) and non-monetized surplus captured by consumers in the form of greater choice, lower prices, and new features. This definition excludes what you might call social welfare, or the externalities that affect the public. I will address that in the next chapter.

If you’re a creative, policymaker, academic, or social/cultural critic, maybe this is not how you think about value. But everyone with even a passing interest in how a business sector evolves should care a lot about changes in economic value creation.

Everyone with even a passing interest in how a business sector evolves should care a lot about changes in economic value creation.

The simple reason is that management decisions are driven by economic incentives. Like it or not, money makes the world go ‘round. In media, those incentives determine what movies, games, and albums get made and what shows get greenlit, renewed, and canceled; which artists get signed and marketed; the way that companies use consumers’ first-party data; employee compensation and benefits; the advertising load on your favorite streaming service, TV network, or social network; and the products that are produced and supported.

Value Chains

The effects of disruption are usually observed and analyzed at the level of the firm or value chain. As a reminder of the definition I provided in Chapter 1, a value chain (which I use interchangeably with ecosystem) is the sequence of activities across multiple firms that delivers a product or service to the end user, spanning suppliers, complementors, intermediaries, distributors, and even consumers. Note that the conventional definition of a value chain doesn’t include consumers. But since our definition of value includes consumer surplus, consumers should be considered part of the value chain too. As we’ll discuss later, this is particularly important for our purposes, because value usually flows to consumers in a disruption.

Value Pools

The last piece of the puzzle is the value pool. If value is total economic surplus, then a value pool is the smallest practically useful unit of that surplus—the atomic unit—a discrete activity where a measurable amount of value is created, captured, or both.

A value pool can be:

A monetized pool. In media, that includes different revenue streams, like subscriptions, advertising, purchases, licensing, ticket sales, and merchandise.

A non-monetized pool that is still measurable or can be approximated. This might be a feature or capability that increases willingness to pay, engagement, retention, conversion, or bargaining power. For example: recommendation engines, identity/status features, community tools, or creator monetization infrastructure.

Consumer surplus. That’s the excess value that accrues to users, in the form of more choice, lower prices, time saved, or better experiences.

The concept of the value pool is important for a couple of reasons. First, even though disruption is often analyzed at the level of the firm or ecosystem, it actually occurs at the level of the value pool—a revenue stream or feature. New entrants target value pools, not companies. Second, the value pool is also the level at which managers can respond, because they must allocate resources against discrete activities.

With that out of the way, we’ll explore the effects of GenAI on value in media.

Sometimes, Disruption Grows Value—But Probably Not This Time

In Christensen’s language, disruption grows the value of an ecosystem when new entrants compete effectively with “non-consumption.” They bring new customers into the market, either because those customers were previously priced out or because they’re attracted to new features the upstarts introduce.

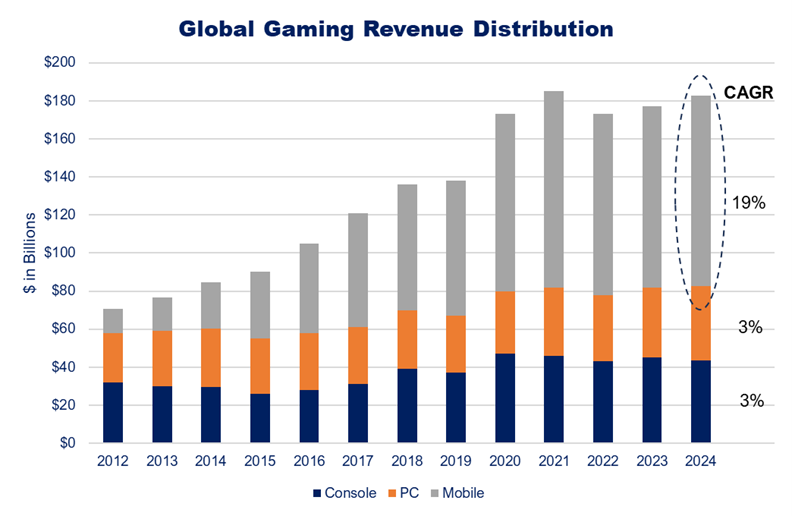

Within media, the best recent example is the way that mobile gaming grew the whole market, as we discussed in Chapter 8. Mobile gaming, especially casual games, appeal to a very different customer base than hardcore console games. They tend to skew older and more female. A lot of the people who play Candy Crush or Bejeweled would probably not call themselves “gamers.” You can see this in Figure 118, which I reprinted from Chapter 8: while mobile grew from a small proportion to over half of global gaming industry revenue over the past decade or so, PC and console games also grew over that period. Mobile expanded the market.

Figure 118. Mobile Grew the Market

Source: Newzoo, Author analysis.

Unfortunately, it is hard to bet today that GenAI will grow the total media pie. As I mentioned in Chapter 4, the media business is about monetizing attention (the amount of time spent) and engagement (the quality of time spent). Could AI increase one or both? Perhaps. But a slight perhaps.

Right now, time spent with media is no longer growing, as I showed in Chapter 4. Maybe AI changes that. Perhaps self-driving cars free up commuting time (which averages 54 minutes per day in the U.S.), clearing the way for more media consumption. Or maybe AI is so effective at replacing knowledge work that governments introduce universal basic income (UBI) and people can stay at home and watch short-form dramas all day. (I think that is a dystopian outcome, but it’s a possibility.)

Alternatively, maybe GenAI enables new experiences that boost engagement and encourage people to spend more on media than they do today. For instance, maybe consumers would pay more for personalized media or the ability to create their own versions of Star Wars or Harry Potter.

So, GenAI could boost time spent and engagement. But if you’re allocating resources or making big career decisions, it’s hard to bet on “could.”

Figure 119. The 4Cs of Value Redistribution

Source: Author.

How Value Gets Redistributed: The 4Cs

While we can’t be confident that GenAI will meaningfully increase value in media, we can be sure it will redistribute it.

At the heart of this redistribution is a simple question: What will become more valuable when content is functionally free? That might evoke some simple answers too. A few things might easily come to mind, like curation, distribution, proof of human creation, live events, etc. But we need a rigorous way to think through this question. We need a framework!

As I mentioned briefly at the beginning of the chapter, in a disruption, value tends to shift away from incumbent value pools in four directions, or what we can call the 4Cs: Challengers, Consumers, Complements, and Chokepoints (Figure 119). For media companies, the last two are the most important and where we’ll focus the rest of this chapter.1

Challengers. This just means disruptors, renamed for alliterative purposes. As underscored by Netflix’s market capitalization, successful disruptors siphon off value.

Consumers. As mentioned before, in our definition, consumers are part of the value chain. They typically benefit from disruption, too. This also follows from the definition of disruption: disruptors enter a market with lower prices and introduce new features. Incumbents often eventually follow suit. So, it shouldn’t be surprising that disruption reduces consumer prices and increases consumer choice. Obviously, in media, the internet ushered in both lower prices and much more consumer choice, as we explored in Chapters 4, 5, and 6.

Complements. This describes a demand-side consequence of disruption. Complements are products and services used together. When a key input becomes cheap and abundant, demand and willingness to pay often shift toward complementary goods and services that become relatively scarce in comparison. Or, entirely new complements can emerge as the abundance makes new things possible or creates new frictions. In this chapter, I use “complements” as shorthand for “complementary value pools that get bigger when content becomes cheap and abundant.”

Chokepoints. This describes a supply-side phenomenon. A chokepoint is a structural position of control, a limiting factor or bottleneck in the value chain that mediates the flow of value after an input becomes abundant. A chokepoint is typically a scarce asset, capability, or market position that others must navigate or access to reach customers, monetize, or scale. Whoever controls a chokepoint gains bargaining power and can extract what economists call economic rent. The chokepoint itself is a position and the rent it produces is a value pool.

Complements describe where value is created; chokepoints describe where value is captured.

To understand the relationship between complements and chokepoints, think of it like a freeway. When cars become more abundant, freeways are a complement that become more valuable. (So are gas, repair services, etc.) If there are toll booths, these become the chokepoints in the system that extract economic rents. Complements describe where value is created and chokepoints describe where it is captured. But the “if” two sentences back is important. Most complements don’t become chokepoints.

Take the canonical example from the internet era, the rise of search. As the volume of information online exploded, the ability to navigate all this content—to search it—became a new, valuable complement. Initially, search was not a chokepoint, because no one controlled it. (Search providers included Altavista, Lycos, Ask Jeeves, Go, Yahoo, and others.) But with better algorithms, network effects, and eventually scale advantages, Google consolidated control over search and extracted almost all the economic rent.

Among these four categories of value shift, the first two are straightforward. If you are a disruptor using GenAI to successfully compete with incumbents, good for you. Value will shift your way. If you are a consumer, the emergence of GenAI will also benefit you, in the form of more content at lower prices and new GenAI-enabled experiences. (There may be costs too, which we’ll discuss in the next chapter.)

If you are a media incumbent, supplier, partner, or technology vendor, that’s where it gets a bit more complicated. The bad news is that value will shift away from some of your current value pools. The good news is that if you position yourself correctly—if you can develop complementary value pools that users value and control chokepoints that govern how value flows—you can mitigate the adverse effects or even benefit from disruption.

Let’s dig deeper into both complements and chokepoints, including which ones stand to benefit.