Media’s Shift from Growth to Optimization

Why it Was Inevitable and What Happens Next

[Note that this essay was originally published on Medium]

Note: After posting this I got a lot of feedback, including pushback. For a summary and my response, see here.

I ran Investor Relations at TimeWarner from 2008–2013, the period when Netflix emerged as a disruptive force in TV. In investor meetings, our CEO Jeff Bewkes was invariably asked about the threat Netflix posed to the TV ecosystem. He would often respond, sometimes in exasperation, “You can’t jam an $80 thing into an $8 thing!” His point was that Netflix, priced at $7.99 at the time, couldn’t replace the entire pay TV bundle because it could never absorb its costs.

He was right, of course. A decade or so later, Netflix’s Premium tier costs $20 and it has not subsumed the entire pay TV bundle. But it fundamentally changed the economics of the TV business. Netflix was always willing to operate at much lower margins than traditional TV networks. Fearful of watching their traditional businesses eroded away, all of the major TV networks companies reluctantly followed Netflix into streaming. That meant they were constrained by Netflix’s price umbrella and beholden to its consumer value proposition and associated cost structure: massive investments in content, product, streaming infrastructure and analytics. They reasoned, correctly, that they had little choice; if they were inevitably going to be cannibalized, they better cannibalize themselves.

In the last six months, however, the consequences of this transition have become clearer. Increasingly, it looks like Netflix’s cost structure — and therefore the cost structure of the entire streaming business — was predicated on a total addressable market (TAM) that was optimistically high and churn that was optimistically low. Changes in these assumptions will have a material adverse effect on the expected profitability of the business.

I’ve written about these topics before, including One Clear Casualty of the Streaming Wars: Profit and Is Streaming a Good Business?. In this follow up, I address three questions: 1) is the slowdown in streaming subs a temporary lull (spoiler: probably not)?; 2) what are the financial implications?; and 3) if you’re a media conglomerate who’s been betting that streaming is a major growth and profit engine, what do you do now?

Tl;dr:

There is ample evidence that the U.S. streaming market is maturing.

Streaming penetration of broadband homes is approaching saturation; the number of streaming services per streaming home appears to be topping out around 4; churn has picked up, implying consumers are actively managing their monthly spend; and there is growing willingness by consumers to trade off watching ads for lower bills, also suggesting price sensitivity.

The chief financial implication of this slowdown is that aggregate TV industry profits probably peaked a few years ago: 1) overall TV revenue is probably near a peak, since the growth in streaming revenue will probably only roughly offset the declines in traditional TV revenue over the next few years; and 2) even after the media conglomerates work through the current period of high startup investment in their streaming businesses, steady-state streaming margins are likely to be much lower than traditional TV.

This prognosis is even more challenging for most of the media conglomerates. Other than Disney, none are likely to retain the same share of the streaming market that they have in traditional TV.

What’s a media conglomerate to do? The only choice is to transition back to a focus on optimization and away from subscriber growth.

This framing helps explain some of the recent industry news and predict what’s likely to happen next.

Why is Streaming Sub Growth Slowing?

Over the last two quarters, growth in streaming subscribers has fallen markedly in the U.S. As everyone who follows the sector knows, Netflix lost subscribers in 1Q and 2Q 2022 in North America (Figure 1), raising the prospect that these markets (the U.S. and Canada) are now saturated. If there is any doubt that this is disappointing, keep in mind that for years Netflix has spoken of a U.S. TAM of “60–90 million” homes (for instance, here’s a reference from 1Q 2014). Netflix ended 2Q with about 73 million subscribers in “UCAN.” Assuming the U.S. represents ~90% of Netflix’s North American subs (pro rata with the U.S. and Canadian populations), that implies it is peaking at about 65 million subs in the U.S., the low end of the range.

Figure 1. Netflix Subscribers Have Stalled Out in North America

Source: Company reports.

According to Antenna Data, this slowdown is also playing out industry-wide, as gross adds fall and disconnects rise (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Slowdown is Occurring Across the Industry

Source: Antenna Data, Author estimates.

A key question is whether the slowdown is a temporary lull or not. If it reflects a reversal of COVID-19-related pull through of demand, growth should rebound once it works through the system. If it reflects market maturation, then it won’t. The data strongly suggest it’s the latter.

Point #1: Streaming Penetration is Near Saturation

The growth in streaming subscriptions is a function of two things: growth in the number of homes that use streaming services (penetration) and the number of services per streaming home.

As shown in Figure 3, the proportion of U.S. homes that use streaming is approaching saturation. According to Census Bureau data, at the end of last year roughly 94% of U.S. households had broadband service. Based on data from Parks Associates, 82% of them had at least one streaming subscription. How much higher this will go is not clear. As a reference point, pay TV peaked at 87% penetration of all TV households in 2011.

Figure 3. U.S. Household Penetration of Broadband and Streaming are Reaching Saturation

Source: U.S. Census, OECD, Parks Associates.

Point #2: Consumers are Hitting the Wall

The number of services per household also seems to be topping out. There are arguably eight “major” general entertainment streaming services: Netflix, Prime Video, Hulu, Disney+, the pending combination of HBO Max and discovery+, Peacock, Paramount+ and Apple TV+ (not to mention ESPN+). Is there room for all of these in the average streaming video household?

Intuitively, the answer is no. Traditional pay TV has been overserving consumers for years. (To put it in the language of Clayton Christensen’s disruption theory, pay TV has been delivering consumers a product that is more than “good enough” — the very circumstance that makes an industry ripe for disruption.)

From the 1980s through the early 2010s, cable programmers and distributors both benefitted from continually adding channels to the bundle. This justified annual price increases that outstripped the rate of inflation and, with few choices, consumers absorbed the higher prices. As shown in Figure 4, according to Nielsen data, the average number of networks available climbed steadily, even as the average number of channels watched did not. Every year, people were paying for more networks they didn’t use.

Figure 4. Consumers Have Historically Paid for A Lot of TV Networks They Don’t Watch

Source: Nielsen.

Streaming offers consumers much more choice. The key question — which has loomed larger as more streaming options have come to market — is how will consumers react when they are empowered to better align consumption and expenditure? It looks like they are hitting the wall at around four services per home.

As shown in Figure 5, based on a bottoms-up tally of all SVOD subscriptions and the estimated number of streaming homes (from Figure 3), at the end of last year, the average streaming household had about 3.7 services. Also note that the growth rate in services per home slowed significantly last year. After a surge of ~35% in 2020, likely spurred on by the COVID-19 pandemic and the launch of several new services (Disney+ in 4Q 2019 and both HBO Max and Peacock in 2Q 2020), services per home grew about 9% in 2021.

Figure 5. Post a Pandemic Surge, Growth in Services per Household is Slowing

Source: Parks Associates, Author estimates.

Point #3: Growth of AVOD and FAST Imply Consumer Price Sensitivity

Reports of the death of TV advertising have proven premature. That’s good news for advertising, but also implies high consumer price sensitivity.

For years, the growth of streaming was equated with the decline of TV advertising simply because there was much less advertising on streaming services. The largest SVOD providers, Netflix and Prime Video (currently) have no ads, and Hulu, the third largest player, carries a lower ad load than traditional TV (roughly 1/2 as many ad minutes per hour). It was assumed that people were adopting streaming in part because they hated ads. As more viewership steadily migrated over to ad-free or ad-light streaming TV, it seemed inevitable that “premium video” advertising (i.e., advertising in professionally produced linear and streaming TV) would decline.

Ironically, it was Hulu’s decision to launch a premium-priced advertising-free tier in 2015 that would prove to be a turning point for streaming advertising. After launching the new tier, Hulu found that the majority of new subscribers still chose the ad-supported option and these subscribers’ satisfaction with the ad-supported service increased. It turns out that consumers don’t hate ads when the value exchange for watching them is explicit.

It turns out that consumers don’t hate ads when the value exchange for watching them is explicit.

Since then, there has been a resurgence of advertising on streaming. Today, there are numerous scaled FAST/AVOD services from which to choose (Pluto, Tubi, Roku Channel, Xumo, the Peacock free service) and most of the major SVOD services offer or plan a less expensive, ad-supported option. Discovery+, Hulu, HBO Max and Paramount+ all offer an ad-supported tier and Disney+ and Netflix both plan to launch ad-supported options. According to Magna Global, this year FAST and AVOD will generate close to $15B in advertising revenue (this excludes YouTube, TikTok, Twitch and other short form or user-generated video advertising).

Based on Antenna data, for those services that offer an ad-supported tier, in 1Q 2022 about half of new signups took the tradeoff of a lower price in exchange for watching ads (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Around Half of Consumers Opt for Ad-Supported Tiers When Given a Choice

Source: Antenna Data.

This is all good news for the broader advertising ecosystem. However, consumers’ willingness to trade off their time and attention for lower subscription fees also provides evidence of their rising price sensitivity as the number of services per home, and the monthly bill, rises.

Point #4: High Churn Also Suggests Consumers are Actively Managing Spending

Relative to traditional pay TV, consumer switching costs for streaming are far lower, for two reasons: it’s possible to cancel with just a few clicks and the opportunity costs to cancel any individual service are lower when all networks aren’t bundled together.

Churn for streaming services is surprisingly high, particularly for what could be called non-core services (i.e., not Netflix or Disney+), as shown in Figure 7. The inference is that consumers are keeping a few core services, but actively churning out the rest depending on what content is available. This behavioral change — toward active management of subscriptions — is another reason to believe that consumers are reaching their saturation point.

Figure 7. Churn for “Non-Core” Streaming Services is Much Higher

Source: Antenna Data.

What Are the Financial Implications of Slowing Streaming Subscriber Growth?

The key financial implication of this market maturation is that on current course, aggregate TV industry profits (by which I mean traditional TV plus streaming) probably peaked a few years ago. There are two reasons: 1) the growth in streaming revenue will probably only roughly offset the declines in traditional TV revenue, resulting in flattish overall revenues; and 2) even after the media conglomerates work through the current period of high startup investment, steady-state streaming margins are likely to be much lower than traditional TV. This prognosis is even more challenging for most of the media conglomerates. Other than Disney, none are likely to retain the same share of the streaming market that they have in traditional TV.

Total TV Revenue Probably Stays About Flat

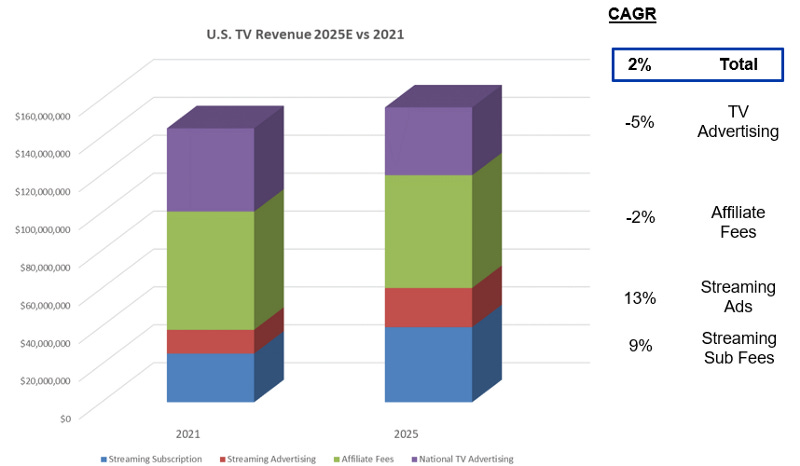

As shown in Figure 8, I estimate that in 2021, the U.S. market for streaming was about $38 billion, compared to roughly $106 billion for traditional TV affiliate fees and advertising. (Note that the traditional TV figures reflect wholesale revenues that accrue to the TV networks, not retail fees paid by consumers to Comcast, DirecTV, etc.) The point is that, given the size differential, streaming must grow much faster to offset declines in linear TV revenue.

Figure 8. Traditional TV Networks Revenue is About 3X Streaming

Note: Advertising is national TV advertising, less syndication. Streaming advertising includes AVOD/FAST, but excludes short form (YouTube, TikTok, etc.). Source: Magna Global, Author estimates.

The good, and somewhat surprising, news, is that traditional TV has continued to grow low single digits over the last few years despite the rise of streaming (Figure 9). That’s been driven by continued growth in affiliate revenue, as affiliate fee pricing has offset pressure on both advertising revenue and pay TV subscribers.

Figure 9. Linear TV Has Continued to Grow Despite Streaming Competition…

Note: National TV Advertising excludes syndication. Source: Magna Global, Author estimates.

Figure 10. …But That Seems Likely to End

Note: National TV Advertising excludes syndication. Source: Magna Global, Author estimates.

As shown in Figure 10, however, I expect that period of growth to end. Considering likely recessionary pressures in 2023 and continued declines in linear TV delivery, I expect TV advertising declines to accelerate over the next several years. I also expect affiliate revenue to decline modestly over the period. As shown in Figure 11, based on MoffettNathanson data, even inclusive of virtual MVPDs, as of 2Q 2022 pay TV subscribers were declining at 6% annually and tracking to be down even more by yearend. The question is whether affiliate fee pricing will be enough to offset the unit declines. Probably not. Affiliate fee pricing is highly opaque, but anecdotally rates are growing about 5–6% per year. An important indicator is the buyers themselves. As shown in Figure 12, total video programming spending started to decline on a year-over-year basis for both Comcast and Charter in 4Q 2021, suggesting that affiliate fee increases are no longer sufficient to make up for the decline in subs.

Figure 11. Pay TV Subs are Declining 5% Y/Y

Source: MoffettNathanson.

Figure 12. Declining Programming Costs for Comcast and Charter Foreshadow Declining Affiliate Revenue for Programmers

*Normalized for sports programming rebates in 1Q-3Q 2020 due to COVID-related cancellations. Source: Company reports, Author estimates.

Conversely, streaming should keep growing at a rapid clip. I estimate that streaming revenue will grow about 12% annually between 2021–2025. This estimate is driven by a few variables: I assume streaming households grow slightly faster than household formation (as penetration continues to climb slowly); services per streaming household grows mid single-digits each year (to reach about 4.5); service providers do not see much growth in effective subscription prices (as a mix shift toward lower-priced advertising supported tiers offset price increases); and streaming advertising grows mid-teens.

Overshadowing the specific assumptions underlying these forecasts, however, is the simple math: as mentioned before, given the relative sizes of the traditional pay TV and streaming revenue pools, streaming has to grow almost 3X as fast as pay TV declines for aggregate TV revenues to stay flat. As shown in Figure 13, I expect that will be the outcome: total TV revenues remain relatively stagnant over the next few years as growth in streaming offsets pay TV revenue declines.

Figure 13. Aggregate TV Industry Revenues Will Likely Stay About Flat

Note: National TV Advertising excludes syndication. Streaming advertising includes AVOD/FAST, but excludes short form (YouTube, TikTok, etc.). Source: Magna Global, Author estimates.

Streaming Margins Will be Substantially Lower

All of the media conglomerates are currently incurring heavy investment spending to support their streaming businesses. But even once they work through this period, steady-state streaming margins will likely be much lower than traditional TV.

Figure 14: Historically, TV Networks Margins are in the Mid-High 30%-Range

Note: Disney is on a September fiscal year and Fox is on a June fiscal year. 2019 precedes push into streaming. Source: Company reports.

I wrote about streaming margins in detail in a recent essay (Is Streaming a Good Business?), but here’s the basic idea. Historically, TV networks margins were 20–40%, among the highest in the broader economy (Figure 14). Streaming margins are unlikely to reach the low end of this range.

Now that Netflix has stopped growing in North America, it is finally possible to determine the steady-state unit economics of a Netflix sub.

It’s possible to see why by examining Netflix’s financials. Now that Netflix has stopped growing in North America, it is finally possible to determine with some degree of confidence the steady-state unit economics of a Netflix sub. Those economics are daunting for almost every other streamers. As shown in Figure 15, despite its massive scale, I estimate that Netflix spends about $10–11 in monthly operating costs per subscriber. Importantly, ~$5 of this is non-programming spending.

Figure 15. Netflix Spends About $11 per Sub per Month in North America

Source: Company reports, Author estimates. Note: Reflects content amortization, not cash costs.

As I explained in more detail in that essay, the media companies are likely incurring at least as large, if not larger, non-programming unit operating costs as Netflix. One reason is the higher churn mentioned above; for a given level of subscriber acquisition cost (SAC), higher churn means a shorter customer life and, therefore, a higher monthly amortization of SAC (or phrased differently, higher ongoing marketing costs). This implies that the media conglomerates are spending $6–8 monthly per subscriber even before any content costs. For many of them, that alone approaches or exceeds their ARPU (Figure 16). Assuming comparable spending on content as Netflix, on the current trajectory it will be hard for most of the media companies to turn a profit, even at scale.

Figure 16. Most Streamers’ Costs > ARPU

Source: Company reports, author estimates. Note: All as reported as of most recently-reported quarter, with the following exceptions: HBO Max from 1Q22 AT&T earnings report; Peacock based on commentary in Comcast 4Q21 earnings that service had 24.5MM monthly active accounts (MAA) and 9MM paying subs, with ARPU for paying subs “approaching $10” — as of 2Q22, it had 27MM MAA and 13MM paying subs; Discovery+ based on guidance last provided December 2020, assuming mix of 50/50 ad-free and ad-lite plans.

Other Than Disney, No One Media Company is Holding Share

So, on current course, the aggregate TV profit pool will likely be smaller in five years than it was a few years ago (before the current period of heavy investment spending). But not everyone will fare equally. As shown in Figure 17, Disney is the only conglomerate that is retaining share in the transition to streaming.

Figure 17. Traditional and Streaming TV Revenue Share, 2021

Note: Traditional revenue includes network affiliate and advertising revenue. Streaming includes SVOD and AVOD/FAST revenue, but excludes short form (YouTube, TikTok, etc.). Assumes no directly attributable revenue for Amazon Prime Video. Represents Fiscal 2021 for Disney (September FY) and Fox (June FY). Source: Company reports, Author estimates.

What Now? The Transition to Optimization from Growth

Above, I used the phrase “on current course” a few times. How can the industry change course? Well, to state the obvious, it needs to raise revenue, lower costs, reduce churn, extend the tail on linear TV and figure out how to extract the most value possible from each content asset.

In other words, it needs to shift its focus back to optimization and away from streaming subscriber growth. That has long been the essence of the entertainment business. This framing helps explain some of the recent industry news and predict what’s likely to happen next.

What Do I Mean by Optimization?

Every business is a multivariate optimization problem. But media businesses inherently have more variables than most (Figure 18).

Content is an information good, which means it has very high fixed costs and low marginal costs. Since pricing is therefore not constrained by marginal cost, it has wide pricing flexibility. Its value is primarily emotional, not functional, so there is a wide variation in consumer willingness-to-pay. Like other information goods, it is extremely flexible, in the sense that many price discrimination or “versioning” models are possible (bundled/unbundled; windowed/”day-and-date;” rent/sell; one-time transaction/ongoing subscription; ad-free/ad-supported/ad-light; full-featured/no frills, etc.). Successful IP is evergreen and extensible, creating opportunities for sequels, spinoffs and reboots and multi-channel, multi-modal exploitation (such as into other forms of media, games, merchandise or events). Many providers are vertically integrated and global, so they must choose whether to sell wholesale or D2C, whether to retain or license rights, which markets to enter, and so on. Digitization enhances all of these elements, enabling an almost infinite combination of price and features.

Figure 18. The Media Business Has a Lot of Levers

Source: Author.

The Media Business Has Always Been About Optimization — Until Recently

The history of the media business is about finding new ways to squeeze more value out of a given content asset. A good example is the windowing of a film. Traditionally, films cycled through several windows in the 8–10 years after premiering: theatrical, then home entertainment (rental and sell through), then premium TV (HBO, Netflix, Showtime, etc.), then free broadcast TV or basic cable networks, then back to premium TV, then finally bundled and licensed as “library” content to free TV, premium TV, SVOD or AVOD yet again. Each window offered consumers different tradeoffs, such as between time delay, rent or purchase, subscription or one-time, bundled or unbundled, uncensored or censored, paid or “free” (advertising-supported).

In recent years, media companies have moved away from optimization as they focused foremost on the growth of their streaming services.

In recent years, media companies have moved away from this practice of optimization as they prioritized the growth of their streaming services. To drive subscribers, they offered their streaming services at low prices (often, substantially lower than they generate in wholesale affiliate fees for the same content packaged into traditional linear networks); collapsed or shrunk theatrical windows; aggressively ramped up content spend; reallocated content budgets away from high-margin linear networks to low-margin streaming services; and curtailed or stopped licensing content to third-parties.

With growing evidence that the streaming business will be neither as large nor as profitable as many hoped, the needle is swinging back. This is the point that WarnerBros Discovery (WBD) executive JB Perrette was making when he presented the slides below (Figure 19) on the company’s recent 2Q 2022 earnings webcast. Seduced by the promise of streaming, the industry had strayed from its roots. Now, it has no choice but to go back.

Figure 19. Optimization vs Streaming Growth-at-all-Costs

Source: WarnerBros. Discovery.

What Does Optimization Mean in Practice?

In recent months, there have been numerous examples of this shift back to optimization and away from streaming subscriber growth-at-all-costs. Here’s a non-exhaustive list:

Netflix’s announced move into the advertising business

Netflix’s efforts to monetize password sharing

Netflix cutting back on comedy special payouts

Speculation that Netflix will move away from its binge model

WBD’s statement that it will “fully embrace theatrical”

Disney reportedly exploring an Amazon-Prime like service (or what Matthew Ball years ago referred to as Disney-as-a-Service).

Reports that WBD will repurpose HBO originals on TNT and tbs.

Reports that NBCU is seeking to cut $1 billion from its networks budgets and is contemplating giving back the 10PM hour on NBC to its affiliates.

I expect we’ll see a lot more of these kinds of announcements and speculation, categorized in four areas: monetization, retention, cost and portfolio. In addition to the examples above, here’s a quick sketch of what each may mean in practice.

Monetization

Aside from Netflix and Disney, it is a matter of debate to what degree the other streamers have much pricing power. But there are other ways to boost revenue besides price hikes:

Advertising-supported tiers open up a large number of ways to drive revenue, including ad loads, advertiser mix, sponsorships, new advertising formats and data-driven targeting and attribution products;

Offering premium tiers, which might include enhanced features like early access to content, access to talent or adjacent products and services, like merchandise, membership clubs or events;

Launching family sharing plans, as Netflix has started outside the U.S.;

Solidifying theatrical windows;

Selective content licensing to third parties, especially in non-core jurisdictions or downstream windows;

Acquisition and Retention

A slowdown in subscriber net additions will increase the importance of retaining existing subscribers and a more granular understanding of LTV/CAC (customer lifetime value/cost of subscriber acquisition). This will require service providers to better understand why subscribers initially join, why they churn and LTV/CAC within different acquisition channels. Are certain cohorts more likely to churn? Are there different churn profiles depending on acquisition channel? Do promotions work? Do fans of certain content genres have different propensities to churn? How does the scheduling of content affect churn? Depending on the answers to these kinds of questions, possible actions may include:

Tailoring acquisition campaigns to different subscriber cohorts;

A more purposeful approach to the timing of tentpole content releases and movement away from binge models;

Creating adjunct products, services or content around consumers’ favorite IP to keep them engaged year-round;

More concerted bundling efforts between affiliated services (like Disney’s bundle of Disney+, Hulu and ESPN+);

Bundling partnerships between unaffiliated streaming services (Peacock and Paramount+?) or with distributors (such as bundling with wireless or broadband service or enabling connected TV providers to sell service bundles);

Making it easier for “serial churners” to cycle off and on;

And offering incentives for subscribers to enter longer-term relationships, like this HBO Max promotion.

Cost, Including Content Optimization

Any business reducing its growth forecasts will naturally turn its attention to its cost structure. Beyond typical “cost out” programs, we expect media companies to re-evaluate their largest discretionary expenditure: content. Not just tightening up content budgets or shifting toward lower-cost programming (e.g., more unscripted), but also approaching content optimization more analytically.

Content optimization consists of determining the optimal window, channel and business model for each content asset along an array of parameters, such as subscriber acquisition and retention, aggregate revenue (including subscription, advertising, licensing, box office and adjacent revenue streams like merchandise) and production and marketing costs. That may mean repurposing streaming content on linear (as WBD is speculated to be considering). It may also mean less absolutism about third-party licensing. Until recently, if a big media company licensed content to a third party it was interpreted as a lack of confidence or commitment to their own streaming service. True content optimization will dictate that sometimes the profit-maximizing decision will be to license a given show or movie.

It’s potentially a rich vein, but it will be hard to mine. Most media companies will need to invest in data management, analytics and business intelligence tools and the data scientists who will make this all work. Besides the heavy technical lift of aggregating data and making it accessible and useful to decision makers, media companies will need to change longstanding practices. Many media companies are organized in silos, each with its own GMs, development executives, budgets and financial targets. Different executives often run different cable networks; linear networks and streaming services may have different management; and movie studios are often run separately from TV. Objectively evaluating the best window or channel for a content asset will require both a holistic view across distribution outlets and the authority to decide.

It will also require a much heavier reliance on data. Historically, most media companies were wholesalers, so they didn’t have much 1st party data, and many functional areas aren’t accustomed to using it. It also poses a cultural challenge. Hollywood is self-selecting for executives who have high regard for their own intuition. Many will resist the idea of augmenting that intuition with data.

Portfolio

As mentioned above, over the last decade the TV business has transitioned from one of limited consumer choice to almost unlimited choice. This necessitates a change in strategy. When consumers had little choice but to take the pay TV bundle and distributors were willing to keep adding networks to the bundle, it made sense for media companies to keep launching new networks.

Today, when consumers can choose which services they subscribe to, it makes sense to have the fewest number of high-quality, logically distinct networks/brands as possible. A streaming service has to have enough brand recognition and content heft that consumers consider it indispensable. Also, as the traditional pay TV business continues to decline in both subscriptions and viewership, many existing networks will become less viable. The logical outcome is that secondary and tertiary brands will be re-branded to create a more obvious linkage with the primary streaming brand, divested or even shut down.

Optimization is the Only Choice

On WBD’s recent 2Q 2022 earnings call, management laid out its intention to prioritize profits over streaming sub growth. A lot of the subsequent commentary was critical, arguing that WBD was acting out of weakness, hampered by its debt load and HBO Max’s relatively sub-scale competitive position. In my opinion, however, it is not only the right strategy, it is the only viable one.

TV is a textbook example of what Christensen called low-end disruption: an industry overserves its customers with a product that is more than “good enough” at too-high a price; a new entrant comes in with an “inferior” product that nevertheless attracts substantial demand; the new entrant systematically moves up-market to offer successively higher quality (first library content, then kids, then first run syndication and finally original TV and movies), siphoning off more demand in the process; and then the incumbents eventually succumb to the innovator’s dilemma, launching their own competing offerings and cannibalizing themselves.

Like any other industry subject to low-end disruption, it has been inevitable for years that the profit pool of TV would decline. Now it’s becoming clear and the industry is adjusting accordingly. Optimization isn’t sexy; unlike blowing out sub estimates, the Street won’t pay for it until it shows up in the financials. It’s also not the most consumer-friendly approach. Content will be available in different places, in different windows, with different features and at different prices. But for an industry grappling with a structurally-smaller profit pool, it’s the only choice.