[Note that this essay was originally published on Medium]

Source: Getty Images

Tl;dr:

Is all the web3 hype warranted? In a word, yes. Web3 will trigger a shift in cost structures, business models and the distribution of bargaining power (and value) across a very broad proportion of the economy. It could prove as disruptive as the Internet itself.

To show why requires a little theory and a little history.

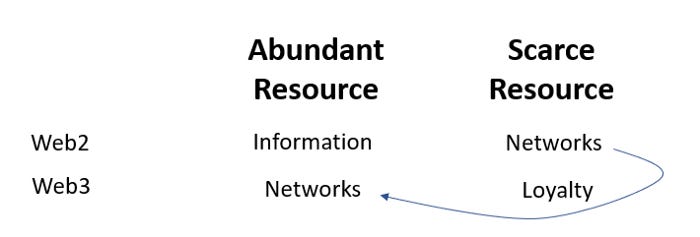

The most disruptive technologies are those that invalidate incumbents’ fundamental assumptions about which resources are scarce and which are abundant. When these disruptions occur across a sufficiently large cross section of the economy, they are considered technological revolutions.

The Internet has been so disruptive, across so many industries, because it unbundled information from costly infrastructure and changed it from scarce to abundant. The companies built on the assumption of scarce, expensive information were disrupted. The most successful web2 companies, by contrast, gave away information to obtain the new scarce resource, networks.

Web3 promises to upend critical assumptions again by making networks fluid and abundant. This is a profound shift.

It is hard to comprehend all the implications, but this framing helps explain some of the most important trends in web3, each of which probably deserve a separate essay:

* Loyalty will become the new scarce resource and business imperative — just as successful web2 companies gave away information to build networks, the most successful web3 companies will give away networks to engender loyalty;

* At the application layer, entry barriers will be even lower than in web2, which is good for the pace of innovation but will also make it harder to create defensible moats;

* Value pools will shift: to consumers; from the application layer to the protocols below; and from gatekeepers to those who create information;

* The advertising economy will be radically altered;

* The opening up of proprietary siloed databases will present almost unimaginable opportunities.

A lot has to go right for web3 to reach its potential and it will take time. But there’s good reason for the hype.

Crypto Has a PR problem

According to a recent study by the Pew Research Center, in the U.S. only 16% of people have ever used or traded cryptocurrencies, 62% have heard about them “a little” and 13% have never heard of them at all. Smart people, like Warren Buffett, Jamie Dimon, Nouriel Roubini and Paul Krugman, have called Bitcoin worthless. The mainstream press perpetuates an equivalency between crypto and meme stocks. It’s hard to explain what crypto is. It’s intimidating to get involved. You need to set up a non-custodial wallet to use DApps or buy NFTs, which is confusing and a little scary. Plenty of stories are floating around about people losing their private keys or getting hacked.

The crypto community isn’t helping. The vocal “number go up” crowd is off-putting, giving the impression everyone is in it for a fast buck. So are the various dogmatic maxi tribes. Even the well-intentioned inadvertently hurt their own cause. Spend even a short time in #cryptotwitter and you will be inundated by technical esoterica and slang (NGMI, apeing, degens, paper hands, looks rare, frens, FUD, (3,3), etc.). There’s constant OG flexing (as in “I’ve been in crypto longer than you”). Calling the uninitiated “normies” only reinforces the impression there’s a cool kids club that they’ll never be asked to join.

But the biggest PR issue for crypto is this: it isn’t clear why you need it.

This PR Problem is Obscuring the Importance of Web3

In the midst of all this, suddenly the term “web3” is everywhere. It promises real applications with real utility that will attract regular people. As boldly implied by the term, web3 proponents believe not only that it will be the gateway to crypto for millions or billions of the uninitiated, but it will usher in a new era for the Internet.

Chris Dixon, partner at a16z and one of the most eloquent advocates of crypto and web3 specifically, succinctly puts it this way:

Web3: Read / Write / Control

So, what is web3 and what’s so great about it?

Web1 is widely regarded as the period of static, read-only webpages built on top of open protocols.

Web2, the world in which we live today, is no longer open. While open protocols are the foundation of the Internet — TCP/IP, HTML, HTTP, SMTP, etc. — there aren’t open Internet protocols for things like identity, commerce, payments, indexing information and many other things. In this vacuum, a handful of massive companies emerged, like Amazon, Google and Facebook, that dominate the Internet today. Thanks to network effects and closed systems, these platforms have built up unassailable networks and vast proprietary deterministic databases. They offer us incredible amounts of information, for free. But, in a Faustian bargain, we have traded our time (their algorithms are engineered to keep us engaged as long as possible to optimize ad revenue); our privacy; our creativity and labor (they own and monetize the content we produce); our freedom (they lock us into their ecosystems); and the competitive vibrancy of our markets (they use their vast resources to outspend or buy emerging competitors). Some argue that because they control our media diet, particularly Facebook, they threaten democracy itself.

What’s so different about web3 is that it is distributed, decentralized and open.

The promise of Web3 is a return to the egalitarian ethos of web1. The root of this promise is that data will not be stored in proprietary servers controlled by a handful of companies, but rather it will be distributed, decentralized and open. It will sit in public blockchains, databases that are replicated and reconciled across hundreds or thousands of computers (distributed). All of these computers, or nodes, will have an equal opportunity (but not right) to make changes to this database (decentralized). And all this “on chain” data, including code (or “smart contracts”), will be publicly accessible (open).

This combination has two critical implications:

Users own their own data. Today, most data are siloed and owned by applications providers. Facebook owns every photo you upload and every record of a “like”; Google owns your search history, the log of every video you watch or upload on YouTube and your driving history on Waze; Amazon owns your purchase and browsing history and every review you ever wrote; Twitter owns your tweets; you don’t own the skins and emotes you bought on Fortnite, Epic is just renting them to you.

In web3, all of this data will be recorded on distributed blockchains, much of which will be represented as NFTs (non-fungible tokens) that you own and control. NFTs are simply a standardized way of digitally representing ownership of unique items. The most visible application of NFTs so far is “JPEGs that you own,” but that obscures the almost limitless possible applications. In our own lives, almost everything we own — houses, cars, pets, clothing, furniture, appliances, favorite frying pans — is non-fungible. The only fungible things you own are probably financial instruments, like cash, stocks or cryptocurrencies. NFTs can verify ownership of anything you can imagine: digital items you buy or earn, like digital collectibles and in-game virtual goods (land, clothing, vehicles, weapons, etc.); elements of your identity; achievements and certifications; health information; memberships; content you create (tweets, blogs, posts, photos, songs, videos); your preferences (music and video playlists and bookmarks); and your online activity (purchase data, search history and browsing, viewing and listening behavior). Over time, NFTs will increasingly extend to offline assets, acting as the title to physical goods you own.

Just like ownership in the real world, ownership in the digital world means you have property rights. You determine what to keep private and what to expose publicly. Where applicable, you can sell. rent, lend or borrow against these assets. You can also take these things with you as you move between digital environments.

Applications are composable and forkable. On smart contract blockchains, like Ethereum, code is also open and publicly accessible, which enables composability. Composable means that DApps can be built on top of other DApps, without permission. This is very different than an API, under which a software application closely controls what data it exchanges. Composability is common in the world of DeFi (decentralized finance), as developers continuously launch new projects that utilize other applications to offer better yield (it is referred to as “money legos”). A related (but more draconian) concept is the idea of forkability. A fork occurs when a developer replicates the code of another application, usually adding improved functionality or governance, and seeks to attract the other application’s users. One high-profile example is the development of decentralized exchange SushiSwap, which was created as a fork of Uniswap and (somewhat successfully) sought to divert Uniswap’s liquidity to its own platform.

Web3 Could be as Disruptive as the Internet Itself

These two implications are important. If we own our own data, we will be able to share in the economic value of what we create; we’ll regain control over our privacy; and, coupled with composability/forkability, we’ll be able to vote with our feet, moving to new platforms that offer better functionality. Web3 promises to shift value, control and bargaining power back to users.

That is a big deal and alone warrants all the excitement. But web3 has the potential to be even more important than this.

Web3 could prove as disruptive, to as many businesses, and across as broad a cross section of the economy, as the Internet itself.

To put the significance of web3 in perspective requires us to zoom out a bit. That’s a euphemism for “I will digress into some theory and history before coming back to the practical implications.”

What is Disruption and How Does it Happen?

The word “disruption” gets thrown around a lot, but according to the late great Clayton Christensen, the father of disruption theory, it has a specific meaning. It is a process by which a new entrant emerges with a less expensive, lower-quality product that attracts price-sensitive low-end or new customers; the incumbents ignore it; and the product gets progressively better until it eats enough of the incumbents’ share that they are toast (see here for a more in depth discussion).

This process has played out umpteen times, such as the way mini-mills disrupted integrated steel mills (Christensen’s canonical example in his first book, The Innovator’s Dilemma); digital photography disrupted film photography; angioplasty disrupted cardiac bypass surgery; PCs disrupted mainframes; mobile disrupted PCs; low-cost airlines disrupted traditional air travel; AirBNB disrupted hotels; Uber and Lyft disrupted the limousine business, and so on. Sometimes it happens slowly, sometimes fast; sometimes it eviscerates an industry and other times it “just” severely pressures profits. But each time, it completely upends industries and radically changes how value is distributed.

Fast or slow, disruption upends industries and changes how value is distributed.

Disruption Happens Because Incumbents are Hamstrung

That’s the how. What about the why? The subtitle of The Innovator’s Dilemma is When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Christensen’s thesis was that “great firms fail” “by doing everything right,” namely listening to their best customers and not allocating resources to the low end of the market.

That’s not why firms get disrupted. That was a plausible explanation for “why” when the book came out in 1997 and no one had heard of disruption theory. Over 20 years later, everyone has heard of it, but companies are still being disrupted.

They get disrupted, even when they can see disruption coming, because incumbents are unwilling or unable to take the radical steps necessary to head off the threat. They have too much vested interest in existing business models, practices and organizational structures. Maybe the necessary changes would pressure profits (and executive compensation); maybe the benefits of the changes would only be realized after the CEO’s expected retirement; maybe public investors wouldn’t support the plan and a flagging share price would attract activists or hostile bidders; or maybe the changes would just be too wrenching for employees.

20+ years after the theory was unveiled, we now know that disruption happens not because incumbents “do everything right,” but because they are unwilling or unable to take the radical steps required to head off the threat.

Companies are Built on Assumptions About Scarcity and Abundance

All business decisions are tradeoffs between scarce and abundant resources. Typically, businesses waste the abundant resource to optimize the scarce one. If labor is scarce, you might outsource or invest in automation; if land is scarce, it will determine where you locate distribution centers, retail stores or manufacturing facilities; if capital is scarce, it will determine how you fund your business or how fast you grow.

Managers know that the relative scarcity or abundance of some inputs move in cycles, like capital, labor or certain commodities. Accordingly, they make tradeoffs that are short or medium term and can be easily (or relatively easily) reversed. But companies are also built on assumptions about which resources are scarce and abundant that they do not anticipate will change. These assumptions and corresponding tradeoffs are at the very heart of companies’ business models: how they are organized; how they are capitalized; which functions they perform in house and which they outsource; their prevailing practices and processes; and even which businesses they are in.

Assumptions about which resources are scare and abundant are at the heart of all companies’ business models.

Truly Disruptive Technologies Change What’s Scarce and What’s Abundant

It follows that one of the major sources of disruption is when a company’s most important assumptions about which resources are scarce and abundant — the assumptions that underlie its business model — prove to be wrong. Truly novel technologies do just that.

As an example, think about the tango between processing power and bandwidth that’s played out over the last 60 or 70 years.

In the first enterprise computing systems, local bandwidth was cheap and processing power was expensive. Dumb terminals were connected over a local area network to a centralized mainframe, which performed the processing.

In 1971, Intel invented the microprocessor, got the yet-to-be named Moore’s Law rolling, and flipped the script. Processing power became abundant. That change birthed the modern computer industry and everything related to it — the PC, peripherals, consumer software, enterprise software, video games and mobile phones, etc., etc.

With all that distributed (and commoditized) processing power in place, capital flowed toward the new scarce resource, bandwidth. In 1970, Corning patented the first fiber optic cable and during the ’90s and ’00s billions were spent laying fiber and putting up cell towers which, along with improved multiplexing technologies, compression algorithms and network architectures, flipped the script again, making bandwidth relatively inexpensive and processing power again relatively scarce. In turn, from cheap bandwidth emerged the cloud, the SaaS business model, streaming media and mobile gaming, among many other things.

The cycle will probably keep going. Applications that require more processing, lower latency or real-time analytics are starting to shift more processing capability back to the edge of the network.

The Most Disruptive Technologies Trigger Revolutions

When these shifts between abundance and scarcity play out across a sufficiently wide cross section of the economy they are called technological revolutions.

Figure 1. Five Technological Revolutions in 250 Years

Source: Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital.

In Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital, Carlota Perez delineated five technological revolutions that have occurred roughly every 50 years since 1771 (Figure 1). The primary message of the book, which is excellent (if dry), is that each of these revolutions follow a similar pattern: technological revolution — financial bubble — collapse — golden age — political unrest. She defined a technological revolution as “a powerful…cluster of new and dynamic technologies, products and industries…generally including an important all-pervasive low-cost input (emphasis added).”

In other words, technological revolutions are marked by a change in which resources are scarce and which are abundant on a grand scale.

As she discussed in an earlier paper, this “pervasive low-cost input” is a key driver of each revolution.

“This quantum jump in productivity can be seen as a technological revolution, which is made possible by the appearance in the general cost structure of a particular input that we could call the ‘key factor’…”

In The Beginning of Infinity, David Deutsch wrote that progress is “…a continual transition from problems to better problems…” In other words, every time you resolve one scarcity, a new scarcity is created.

In this way, each technological revolution is not the result of some random assemblage of technologies, but is propelled in part by the need to alleviate one of the key scarcities of the prior period. I try to illustrate this in Figure 2 (note that this assignment of illustrative key abundant and scarce resources is my estimation, it is not from Perez).

Figure 2. Each Technological Revolution is Defined by a New Abundant Resource

Source: Author.

For instance, during the Agricultural Age, land was plentiful but physical force (i.e., human labor and horsepower) was scarce. That led to the Industrial Revolution and the invention of mechanized tools to resolve this scarcity. During the Industrial Age, physical force was now abundant, but it was difficult and costly to move goods. In turn, that led to the commercialization of the steam engine and development of railroads, which made distance “abundant.” And so on.

Each time, the emergence of a new low-cost input — this shift from scarcity to abundance — has extraordinarily far-reaching effects. It triggers Christensen’s disruption process across multiple industries. As explained by Perez, it also rips apart the social fabric and reshapes the socio-political infrastructure. It’s a big deal.

The Internet Was Disruptive Because it Made Information Abundant

The Internet (which I’m using as shorthand for a suite of technologies: digitization, broadband fixed and wireless networks and inexpensive devices, among many others) has been the mother of all disruptive technologies. Media, retail, financial services, travel, healthcare, telecommunications, technology, consumer products, even manufacturing, have all been affected.

If asked to describe the disruption process for each of these sectors, you might provide a different answer for each. But the common thread is that the Internet made information abundant. Every company needs information to function. Prior to the Information Age, information was scarce and expensive to acquire. It often required large outlays for manufacturing facilities and distribution infrastructure, complex supply chains, retail outlets, and expensive sales forces. It was locked in proprietary R&D reports, product documentation, EDI systems, manifests, customer databases and pricing sheets. Many businesses’ competitive advantage and profits — particularly middlemen of any kind — was based entirely on information asymmetry.

The Internet changed information from scarce to abundant.

The Internet unbundled information from all this costly infrastructure and lowered the barriers to acquire it. There are countless examples, which have been pointed out before. The biggest media company in the world, Facebook, owns almost no content. The biggest lodging company in the world, AirBNB, owns no hotels. Some of the largest transportation companies, Uber and Lyft, own no cars. The biggest news company, Twitter, employs no journalists and owns no printing presses. The biggest cable company, Netflix, owns no cables and does no truck rolls. The biggest car company, Tesla, has no dealers. As famously noted in this article, every piece of hardware advertised in a 1991 Radio Shack ad has been replaced by an app on your iPhone. Use AWS and you can run a successful SaaS business without owning any data centers. Use Shopify and drop shipping and you can run a successful retail operation with no stores or inventory.

As predicted by Christensen, the incumbents who has invested so heavily to acquire information — in R&D, manufacturing facilities, supply chain logistics, distribution infrastructure and sales forces — were hamstrung by enormous sunk costs, established business practices and entrenched vested interests and were unable or unwilling to respond. They got disrupted.

The new entrants, however, recognized that information was now the abundant resource and networks were the scare resource. They gave away information for free to establish and build networks. Network effects and closed systems created high switching costs and strong competitive moats. They are the bedrock of web2.

Figure 3. Web3 Will Make Networks Abundant

Source: Author.

Why Web3 Will Disrupt: Abundant Networks

I will not go so far as to argue that crypto represents the 6th technological revolution. As Ben Thompson pointed out in a recent Stratechery article, Perez herself thinks that we are only at a turning point in the 5th technological revolution, not at the beginning of a new one.

Whatever we call it, web3 promises to once again change which resources are scarce and which are abundant across a very broad cross section of the economy. By enabling users to control their data, networks will become much more fluid and, as a result, abundant. This would be a massive shift.

What will this world look like? Of course no one knows. This is such a profound change, and it’s still so early, that it’s impossible to comprehend all the potential implications and cascading effects. But this framing — of web3 as a shift toward fluid, abundant networks — helps explain and possibly predict some of the most important trends in web3, many of which are inter-related:

Loyalty becomes the new scarce resource. When networks become abundant, what becomes scarce? With much lower switching costs, consumers will theoretically be able to move from application to application, bringing their data, preferences, lists, content and relationships with them. We have already seen the fluidity of users in DeFi yield farming, in which capital flows freely looking for the best yield. If a web3 application is failing users, it is vulnerable to the next best thing — we could call it “experience farming” — or even a fork.

I don’t want to overstate how easy it will be to jump from application to application. If someone shows up with a better version of crypto-Facebook, for instance, it will be non-trivial to coordinate a mass migration to the new platform. There will still be some switching costs. But the key point is that they will likely be far lower than they are now. In this environment, the only way for applications to retain users is to engender loyalty. That won’t mean just having a great UX or being responsive to customer complaints.

In web2, the most successful companies gave away information to build networks. In web3, the most successful will give away networks to build loyalty.

As mentioned above, in web2 the most successful companies gave away information to acquire networks. In the web3, the most successful projects will give away networks to obtain loyalty. What the heck does that mean?

It will mean literally giving networks away by ultimately providing the bulk of equity value to users (in the form of tokens) so they have a vested interest in the application’s success.

They won’t put up gates to switching. There are basically two kinds of switching costs. Positive switching costs are the opportunity costs of leaving (the benefits of the relationship that you will miss). Negative switching costs are the procedural (“pain-in-the-ass” costs) or financial costs you must incur to leave. Successful web3 firms will try to maximize the former and minimize the later. They will try to create a culture, not a prison. They won’t purposely throw up barriers to make it really hard for you to leave.

Web3 applications will need to be “minimally extractive,” i.e., have a much lower take rate than has been commonplace in web2. Facebook retains 100% of ad revenue; Epic keeps 100% of revenue spent on Fortnite in-game items; YouTube retains 45% of ad revenue; Ebay charges up to 15% on the first $2,000 of a sale (depending on the category). By contrast, Axie Infinity keeps a 4.25% fee on all in-game transactions; Opensea charges a flat 2.5%; and the Brave browser pays out 70% of ad revenue to users. Lower “rakes” will likely be a structural component of web3.

DAOs are not some hippie-dippy/quasi-socialist/idealistic BS. In web3, they are an important source of competitive advantage.

Decision making and governance will need to be transparent, if not entirely democratic — enter the DAO. Many companies make decisions that appear to be (and often are) at odds with their customers’ interests and their decision making process is opaque. To engender loyalty, web3 companies will need to be transparent, (at least partially) democratic and make decisions that weigh the effects on all stakeholders. To achieve these goals, many web3 companies are structuring themselves as DAOs (decentralized autonomous organizations) or, as laid out in this post by VC Jesse Walden, going through a process of progressive decentralization. As implied by the name, DAOs are collective organizations in which work, value and governance are shared, all facilitated by tokens, and decision making is transparent. In most DAOs any member may make proposals for organizational actions. The proposals are debated, refined, voted upon and, if successful, enacted. And the DAO’s wallet is publicly auditable, which means anyone can see how it allocates funds. This is a level of transparency that is unheard of in corporate America. It is way beyond the scope of this essay to dig in too deeply into DAOs. They are a fundamentally new form of organization and, if they proliferate, they will have profound effects on how we think about work. For (much, much) more, see this excellent deep dive by The Generalist. The point is this. It is easy to dismiss DAOs as a fringe phenomenon, or — as I did when I first heard about them several years ago — as a hippie dippy/quasi socialist folly that is driven by idealism, not strategy. They are neither. For all the reasons described above, in web3 transparent decision making and inclusive governance could prove a critical source of competitive advantage.

Engendering loyalty will also probably mean spending a lot less on traditional marketing and a lot more effort, if not money, building community on a grass roots basis. More influencers, more “community managers,” fewer Superbowl ads.

Entry barriers and costs are de minimus at the application layer, but how do you build a moat? Relatively recent innovations, like open source code and cloud services, have lowered the entry barriers to launch a business. With web3, these entry barriers are likely to fall even further due to composability. As we are already seeing in DeFi, new applications will be able to easily leverage and/or aggregate existing applications. Even slight enhancements to existing code could prove a viable business. (The trope of two guys disrupting an industry from a suburban garage will be outdated; it’ll be one guy at an Internet café in Bangalore.) As alluded to above, marketing and sales costs may also be far lower because the most successful projects will rely heavily on the grassroots efforts of the community. While all of this is good news for the pace of innovation and new business formation, the obvious flip side is that it may be very difficult to create a defensible moat.

If a market is growing fast enough, moats may not matter for a long time. Also, lower switching costs don’t mean there will be no moats. As discussed in this thread, they will still arguably exist. But when code can be forked, liquidity can be drained and communities can easily grow disenchanted, switching costs are likely to be much lower and moats much harder to establish.

Value pools shift to consumers... This follows from the discussion above, but it is worth making the point explicit. If bargaining power is flowing away from the application layer, value has to be flowing somewhere else. Clearly, consumers are beneficiaries. When we think about the ways profit is divvied up in an industry, we often think about how profit flows along the supply chain (i.e., who has bargaining power over whom) or the relative competitive position of the companies within each segment of the supply chain. But consumers are also “competing” for these profits, in the sense that value shift to consumers is often value shift away from the rest of the value chain. With greater competition at the application layer, it is inevitable that more value will shift to users, whether in the form of direct equity/token participation, lower prices/margins/take rates or better experiences.

…They shift back down the stack... If there aren’t the same moats at the application layer in a web3 world, where are they? Lower in the stack. In 2016, former Union Square Ventures partner Joel Monegro wrote an incisive post titled Fat Protocols, which made the case that while most value accrued to the application layer in web2, in crypto most of the value will accrue to the protocol. (Hope he bought some ETH!) The logic is essentially that, if value is created on top of the protocol, there will always be substantial demand for the native token to extract this value. This is already evident in current trading prices, with much higher market capitalization for Ethereum and other smart contract layer 1/layer 2 protocols (Solana, Polkadot, Avalanche, Terra, Polygon, etc.) than for the applications that sit on top. This idea raises some interesting questions that will probably take years to play out. For instance, will there ever be true interoperability among blockchains and, if so, how will this affect the switching costs (and value extraction) at L1/L2? Also, what value will accrue to the protocols that sit on top of the base protocol (layer 3 protocols), for things like payment processing, custodial services, data management, file storage, DAO tooling, game development, identity, etc.?

…And back up the value chain to information creators. One of the most widely discussed and exciting implications of web3 is that independent creators will be able to retain a direct stake in their product. They can bypass the largest platforms and sell NFTs directly to their most ardent fans — and, in some cases, get royalties on future sales — rather than be at the mercy of YouTube, Instagram or Spotify to pay out a meager revenue share.

There is also a more nuanced reason that value should flow back up the value chain toward content in a web3 world: the declining bargaining power of gatekeepers. Prior to the advent of the Internet, content was scarce and curation was abundant (i.e., “curators” like Reader’s Digest and TV Guide generated little value). The Internet collapsed the barriers to entry to create and distribute content, making content abundant and curation scarce and far more valuable. Facebook (including Instagram), Google (including YouTube), Twitter, Spotify, Pinterest and countless others are essentially curation companies. One could argue that their entire market capitalizations represent a value shift from those who make the content they curate. One of the implications of distributed, open (on-chain) data in web3 is that curation will be democratized. In that environment, curators would have far less bargaining power to extract quasi-monopolistic rents.

The ad economy will change radically. There are two reasons for this, both mentioned above. First, consumers are likely to be far less tolerant of intrusive advertising models. Second, web3 companies are likely to spend a lot less on traditional advertising, funneling these resources toward more grass roots efforts. While there are exceptions, such as the massive marketing outlays of Crypto.com, this seems to be the exception, not the rule. Most web3 companies are spending far less on marketing than their web2 counterparts.

What happens when data is no longer locked in siloes? It’s mind boggling to consider what happens when users control their own data and it’s no longer locked into proprietary networks. In theory, we will be able to rent out, sell or grant our data to anyone. What kind of applications can be spun up at minimal cost when it’s no longer necessary to build up a massive network of users to obtain a suitably large proprietary database? What will happen when it is possible to access and analyze data across multiple open databases? What will it mean for the social sciences, healthcare, cross application gaming (yes, the “metaverse”), cross-modality content recommendation engines or target marketing? Google, Facebook and Amazon have been able to create trillions of dollars of value using this kind of data in siloed systems. What kind of value could be generated if all that data was universally accessible?

Do Believe the Hype

Crypto-utopianism is infectious and sometimes it can be hard to separate what you think should happen from what is likely to happen.

Many things have to go right for web3 to reach its potential. It has to get a lot more user friendly. DApps will need to “abstract away the crypto,” so that people can participate without needing to manage their own wallets. UX will also have to improve to match web2 applications today. There also probably needs to be more seamless interoperability between blockchains. The dominant web2 platforms have to fail in an effort to create a closed proprietary metaverse that renders web3 obsolete. And there likely needs to be some sort of regulatory clarity of crypto, whatever that may mean, to foster continued investment and innovation.

All of this will also take time, measured in years, if not decades. Google and Facebook are indisputably two of the most dominant companies on the Internet today. It’s hard to remember life without them and easy to forget that they went public in 2004 and 2012, respectively, or 9 years and 17 years after Netscape’s IPO marked the coming of age party for the World Wide Web. The shift to web3 will likely be faster, because the technological infrastructure (broadband and smartphones) is in place and consumers are already accustomed to spending hours per day online (almost 7 hours per day, according to this). But it will still take time.

Nevertheless, the hype is warranted. When your friend can’t shut up about web3, she is not talking about mutant apes or building a dream house on Nifty Island. She is talking about a fundamental shift in the cost structure, distribution of bargaining power and business model for anyone who conducts business online. It could have tremendously far reaching effects.