In June 2009, I sat in a press conference and watched Time Warner CEO Jeff Bewkes and Comcast CEO Brian Roberts link arms (figuratively) to launch TV Everywhere and save the pay TV bundle. It failed.

In September, more than 14 years later, Charter and Disney resolved their high-profile carriage dispute with a deal that resurrects the basic premise of TV Everywhere: provide pay TV1 subscribers more value for their dollar. Will it work any better this time? Lately, it’s been hard to find too many bright spots for the big media companies. This could be one. While it’s too late to save the pay TV bundle, there are good reasons to be more optimistic this time.

Tl;dr:

In their push to grow their streaming businesses, the media conglomerates have left linear for dead. The only problem with that plan: linear makes all the money.

The recent Charter-Disney distribution agreement resurrects the idea behind TV Everywhere (TVE): think about linear and streaming holistically, provide pay TV subscribers more value for their dollar and reduce churn.

TVE failed for a few reasons: consumers didn’t understand the value of streaming at the time; it was a crappy consumer experience, including the need to navigate too many apps; and some distributors didn’t really want it to succeed.

Several things are different now.

Pay TV plus streaming is a “good bundle,” in the sense that consumers can clearly see the value of the components; there is clear empirical evidence that “good bundles” reduce churn, as supported by Antenna data on Apple One and the Disney Trio; a combination of linear plus streaming will probably remain the best solution for sports fans for the foreseeable future; the rise of FAST underscores the utility of lean-back linear TV that has been lost in the transition to SVOD; and a growing proportion of consumers think of linear TV and streaming as one holistic experience—it’s all just watching TV on an app.

Another thing that’s different is the degree of urgency and unanimity that something needs to be fixed. The body language from the major participants in the value chain also suggest the rest of the industry may fall in line this time.

As the industry coalesces around the need to “re-bundle,” one of the big questions is: who is the bundler? The existing pay TV distribution system is an obvious candidate and sitting right under the industry’s collective nose. It may not save linear TV, but it should help.

Linear is Worth Protecting

For the last few years, the media conglomerates have been spending heavily on content, technology and marketing for their new streaming services and reallocating resources and attention away from their linear businesses. Figure 1 shows Charter’s summary of this process.

Figure 1. Charter’s History Lesson on the Self-Inflicted Wounds to Linear TV

Source: Charter Communications “The Future of Multichannel Video: Moving Forward, Or Moving On,” September 1, 2023.

The problem with this approach is that linear makes all the money. Over the last few years, I’ve written a lot about why the streaming business is structurally less profitable than linear, starting with One Clear Casualty of the Streaming Wars: Profit and followed by numerous other pieces, like Is Streaming a Good Business?, To Everything, Churn, Churn, Churn and Video’s Fundamental Problem: It Over-Monetizes.

Linear makes all the money.

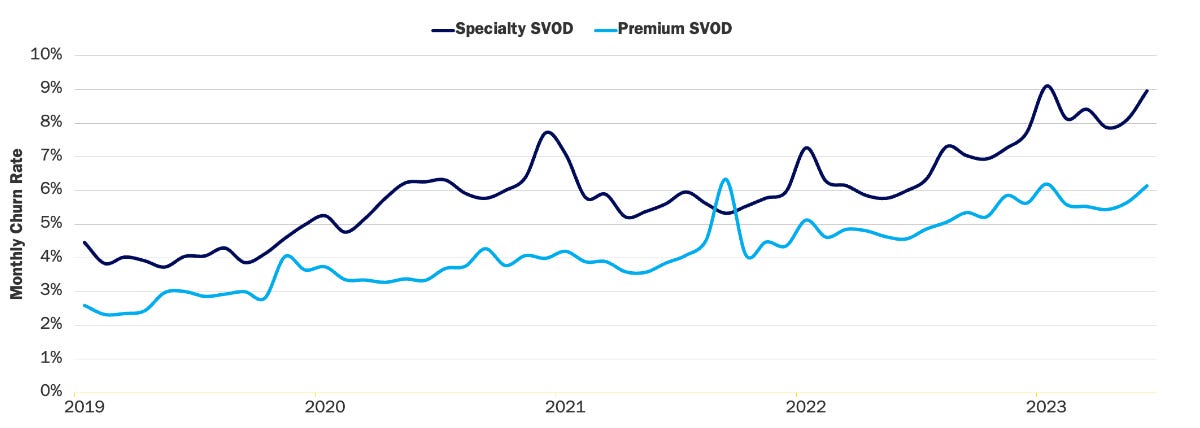

The reasons are pretty straightforward: in streaming, the top line is smaller because consumers spend less than they did on pay TV (since they have more flexibility to pay for what they actually watch) and costs are higher because the business is more competitive and it’s very expensive to run direct-to-consumer businesses with low switching costs (and therefore high churn). These economics are particularly challenging for the sub-scale streamers (and “sub-scale” may ultimately be defined as “everyone other than Netflix”). High churn, in particular, makes for lousy unit economics. And churn is getting worse (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Churn is Getting Worse

Source: Antenna. Note “Premium” is subscriber-weighted average of Apple TV+, Discovery+, Disney+, HBO Max, Hulu (SVOD), Netflix, Paramount+, Peacock, Showtime and Starz. US only; excludes Free Tiers, MVPD & Telco Distribution, and select Bundles.

I won’t belabor the point, but here are two charts that belabor it for me. Figure 3 and 4 show linear and streaming revenue and EBITDA for the media conglomerates (Disney, Fox, NBC Universal, Paramount and WarnerBros. Discovery) in F2022 and the just-reported September 2023 quarter, respectively.

In streaming, not losing money is the new up.

As shown, last year linear generated about $110 billion of revenue and $33 billion of EBITDA, a 31% margin, while streaming generated $36 billion of revenue and $10 billion of losses. This year, all the conglomerates have made progress improving streaming profitability, by raising prices, introducing ad tiers, slowing the pace of content spend (aided in part by the strikes) and cutting marketing costs. Still, in the just-reported September quarter, linear revenue remains more than double streaming and continues to generate roughly 30% margins. Streaming is less of a drag than it was, but still hasn’t reached breakeven.

The commentary around streaming profitability is also telling. In prior years, several of the conglomerates forecasted that their streaming businesses would eventually reach 20% margins. No one has made that claim recently. Not losing money is the new up.

Figure 3. Last Year, Linear Ran 30% Margins and Streaming Lost $10 billion

Note: Reflects aggregate revenue for Disney, Fox, NBCUniversal, Paramount and WarnerBros. Discovery for fiscal 2022 (Disney is September, Fox is June), before intercompany eliminations. Source: Company reports, Author estimates.

Figure 4. Streaming Has Improved, But is Still in the Red

Note: Reflects aggregate revenue for Disney, Fox, NBCUniversal, Paramount and WarnerBros. Discovery for the three months ended September 2023, before intercompany eliminations. Source: Company reports, Author estimates.

If linear is so profitable, why did the conglomerates put all their eggs in the streaming basket? There were a few reasons that seemed reasonable at the time:

Fear of Netflix’s ascendancy and that if it grew unabated it would ultimately be able to price everyone else out of the content market;

Wall Street’s (ultimately-broken) promise that Netflix-like sub growth would be rewarded with Netflix-ish multiples; and

Resignation that the linear pay TV business was in free fall anyway, so why bother trying to save it?

The first one was valid then and is valid now (although it’s very hard to corner the market on $200 billion of global content spend). The second one was pretty enticing at the time, but we know how that worked out. But let’s focus on the last one: what if there is a way to save linear, or at least slow its decline?

Why TV Everywhere Failed

In June 2009, Time Warner Jeff Bewkes and Comcast CEO Brian Roberts jointly announced “TV Everywhere” (TVE), an effort to enable pay TV subscribers to access on demand content at no extra charge. The idea was that programmers would make this content available through their branded websites, mobile and connected TV apps and distributors’ on demand services. Technically, the way this worked was that when, say, a DirecTV customer opened a TVE app or website to watch the TNT app, in the background Turner would communicate with DirecTV to “authenticate” that the subscriber was in good standing. With their announcement, Time Warner and Comcast hoped to establish a template that the rest of the industry would follow.

In the years following, most of the other programmers and distributors eventually fell in line, launching (and authenticating) new apps for CNN, MTV, ESPN, HBO, USA, AMC, etc.

Figure 5. CTV Penetration Was Basically Nil in 2009

Source: Statista.

The goal of TVE was to increase the price-value equation of pay TV and persuade subscribers to “keep the cord,” not cut it. Ultimately, it failed, for a few main reasons:

Consumers didn’t understand the value of what they were getting. When Time Warner and Comcast first laid out the template for TVE deals, no one understood the value of TVE apps. At that time, few even knew what streaming was. Netflix had about 11 million customers in the U.S. (and none internationally), or roughly 10% household penetration. Netflix streaming had no discrete price; it was a free add-on to the DVD-by-mail subscription service. Connected TV penetration was somewhere close to zero in the U.S. (Figure 5), so consumers weren’t accustomed to watching streaming on televisions. There were also no originals on streaming, it just offered old series and movies. TVE apps also had no a la carte price and therefore no marker of value.

In 2009, most consumers had no idea what streaming was, what it was worth or why they should care.

Navigating multiple apps was a poor customer experience. It turns out that no one wanted to navigate to a separate app for each network. Who da thunk it?

Authentication was often a clumsy and frustrating process, sometimes by design. Initially, the authentication process was subject to high failure rates and often required subscribers to log back in. Eventually the technology improved (such as the advent of auto-authentication, which used the customer’s IP address to verify eligibility rather than require the customer to log in), but some cable operators declined to adopt these improvements. They also sometimes refused to authenticate on certain platforms for apparently arbitrary reasons (for instance, at one point Comcast authenticated HBO Go on Apple TV but refused to do so on Roku). The reality is that despite the apparent unanimous support for TVE within the industry, not everyone really wanted it to succeed. Some cable operators were ambivalent about supporting programmers’ apps and third-party platforms because they preferred to control the customer relationship themselves.

In Theory, This Time Should Work Better

On September 11, Charter and Disney announced a resolution to their high-profile carriage dispute. The agreement had several key components:

Charter will make the ad-supported versions of Disney+ and ESPN+ available to certain tiers of customers at no extra charge. Once Disney launches its flagship ESPN network over-the-top (which it has recently said it intends to do in 2025), it will also be made available to certain Charter subscribers at no extra charge.

Charter will market Disney direct-to-consumer products, such as Disney+, to its broadband-only customers (through a wholesale relationship).

Charter is also dropping some of Disney’s less-popular networks, namely Baby TV, Disney Junior, Disney XD, Freeform, FXM, FXX, Nat Geo Wild, and Nat Geo Mundo.

The first component is clearly a resurrection of the idea behind TV Everywhere: think about linear and streaming more holistically, give pay TV subscribers more value for their money and therefore make it less likely they will cut the cord. Will it work this time?

At this point, it is probably too late to “save the bundle,” which I define as stabilizing or even reversing pay TV sub losses. As I’ve written elsewhere (Video’s Fundamental Problem: It Over-Monetizes), pay TV’s chief problem is that it requires consumers to pay too much for networks they don’t watch. The “great unbundling” of TV has enabled consumers to better align consumption with expenditure. It will be hard to put that genie back in the bottle. But to the extent the Charter-Disney model is replicated across the industry—among both other programmers and other distributors—there are a lot of reasons to be optimistic that it should help slow the pace of pay TV subscriber attrition.

TVE Was a “Bad Bundle” and Pay TV Plus Streaming is a “Good Bundle”

I recommend an article called Four Myths of Bundling, by Shishir Mehrotra, which provides a great general framework for thinking about bundles. Of his four “myths,” Mehrotra’s third myth is that, contrary to the perception that consumers always think bundles are a rip-off, consumers like bundles when there is a “…transparent (and reasonable) a-la-carte price for each of the products in the bundle” and they can therefore easily see the discount.

This enables us to draw a distinction between bad bundles and good bundles. From To Everything, Churn, Churn, Churn:

So, we can define two kinds of bundles: “bad” (or forced) bundles, in which it isn’t possible to buy the components individually (like cable TV or the newspaper) and “good” (or voluntary) bundles, in which it is.

TV Everywhere was a “bad bundle” for the reason cited above: consumers couldn’t buy the components a la carte and therefore couldn’t see the value. Pay TV plus streaming is a “good bundle” because it is possible to buy the components separately and the value of buying them together is therefore very clear. By contrast to 15 years ago, today everyone knows what streaming is and people are well aware of the price (so much so that many subscribers use churn as a tool to manage their monthly streaming subscription spend). Charter doesn’t seem to be doing so yet, but eventually pay TV distributors will probably emphasize in their marketing all the additional value that people get with their subscriptions.

Good Bundles Work

The reason why good bundles work is intuitive. They attract, upsell and retain customers they otherwise wouldn’t have: those whose willingness-to-pay (WTP) is lower than the a la carte price of one or more components of the bundle, but whose aggregate WTP for the components is higher than the cost of the bundle.

Let’s look at the math of this, starting with the attract/upsell part first (Figure 6). Consider two streaming services, Plus and Extra, each of which cost $8 per month a la carte, but are bundled together for $12 per month, for a 25% discount. Now, consider customers X, Y and Z. Customer X has a WTP of $10 for each service. He would buy both products a la carte and will happily buy the bundle and get the discount. Customer Y has a WTP of $7 for each. She wouldn’t buy either of them a la carte, but would buy them both at the bundled price. Customer Z has a WTP of $9 for Plus and $5 for Extra. He would buy Plus a la carte and not Extra, but instead purchases the full bundle.

If only sold a la carte, collectively Plus and Extra would generate $24 of revenue (X buys both, Y buys neither and Z buys only Plus). Since each customer buys the Plus/Extra bundle, the bundle generates $36 of revenue.

Figure 6. Good Bundles Provide Consumer Surplus

Source: Author analysis.

Now, let’s do the math on retention. All of them should be reluctant to churn and lose some consumer surplus, which is the difference between WTP and price. Customer X is extracting a consumer surplus of ~$8 for the bundle, compared to $4 if he bought the services separately. Customer Y would not buy either service a la carte, so she loses $2 of consumer surplus if she churns. Customer Z has a consumer surplus of $2 and he loses $1 of this if he downgrades to just purchase Plus.

Aside from the theory, there is ample evidence that good bundles lower churn. The Apple One bundle is a good bundle. The “Premier” plan offers Apple Music ($16.99 for family plan), TV+ ($9.99), Arcade ($6.99), iCloud (2 TB) ($9.99), News ($9.99) and Fitness+ ($9.99), a $~64 “value,” for $37.99. The Disney Trio (Disney+, Hulu and ESPN+) is also a good bundle. The Premium plan (which has no ads on Disney+ and Hulu, but ads on ESPN+, since there is no ad-free version) is $24.99, compared to ~$42 for the three services individually. (Interestingly, both bundles offer a roughly 40% discount.) As shown in Figure 7, according to Antenna data, not surprisingly the churn on the bundled offering is much lower on both Apple One and Disney Trio than either Apple TV+ or Disney+ alone, respectively.

Figure 7. Good Bundles Work

Source: Antenna.

Linear Plus Streaming Will Probably Remain the Best Sports Solution

Currently, being a sports fan—particularly major sports like the NFL or NBA—requires subscribing to linear and, in many cases, at least one streaming service.

Take the NFL. Thursday night games are on Amazon Prime. Both NBCU and Paramount simulcast games on both their respective broadcast networks (NBC and CBS) and streaming services (Peacock and Paramount+). Every Monday Night Football game is available on ESPN, with some simulcast on ABC and streaming service ESPN+. Fox, which doesn’t have a streaming service, makes its games available exclusively on the Fox Network. NBA rights are currently split between ESPN and TNT. For some events, like tennis tournaments, it isn’t unusual for them to be split between linear and streaming.

More sports will make their way to streaming. As noted above, Disney has committed to launching the flagship ESPN network as a streaming service in 2025. WarnerBros. Discovery recently announced the Bleacher Report Sports tier as an add-on for its Max streaming service. The NBA’s current rights deal with Disney (ABC/ESPN) and WBD (TNT) expires after the ‘24/’25 season and there is a lot of speculation that a new deal will carve out a third package for a streaming distributor, such as Amazon or Apple.

Nevertheless, a combination of linear and streaming will probably remain the best option for the foreseeable future. The biggest leagues generally have an interest in the widest distribution possible and may be leery of permitting their licensees to move to a streaming-only model. The biggest events, like the SuperBowl, World Series, NBA Finals, The Masters, The Stanley Cup, will probably remain available exclusively on linear services. And, for consumers, getting an almost-full complement of sports only on streaming will be expensive. An ESPN streaming service is expected to run ~$30 per month. The Bleacher add on is $9.99. Tack on a few more streaming services and the cumulative cost will quickly rival the cost of a basic cable subscription, but with a lot less content.

The Rise of FAST Reinforces the Value of “Lean Back” Linear TV

Putting aside the exclusive programming available on linear—not just a lot of sports, but news, awards shows and other live programming—linear TV has some advantages over SVOD, for some use cases, in some contexts. A holistic bundle of linear and streaming would provide more utility than streaming alone.

In the language of jobs to be done theory, all products and services do one or more “jobs” for consumers. Historically, linear TV has done some jobs that are not filled by SVOD services: keep the viewer “company” with background noise/visuals; spoon feed content with minimal friction; and pleasantly “surprise” the viewer with content he likes but didn’t actively select (or what you could also call “serendipity”). (We all have shows or movies that we would never actively select, but will get sucked into if they appear before us—for me, I can blow a few hours on a Sunday afternoon if I stumble onto The Godfather.) When I was at Turner, it was an open secret that a lot of our viewership during the day was people who left the TV on for background noise as they puttered around or did housework.

The rise of FAST shows that one of SVOD’s greatest strengths is also a weakness.

SVOD’s greatest strength—vast choice—prevents it from filling these jobs expressly because it requires consumers to actively choose a specific show. It takes work to choose. According to a 2019 study by Nielsen, the average U.S. adult spends more than 7 minutes deciding to choose the next show on streaming and often gives up if she can’t find something in time.

The rise of FAST illustrates the demand for passive viewing, especially among those who have cut the cord. Aggregate FAST viewership is tough to find, but it’s growing. Every month Nielsen publishes The Gauge, which shows the viewing share of the largest streaming platforms. In recent months, more FAST platforms have surpassed the ~1% viewing share threshold necessary to be included in the chart (Figure 8).

Figure 8. More FAST Platforms are Appearing in Nielsen’s The Gauge

Source: Nielsen.

The Distinction Between the Linear and Streaming Consumer Experiences is Blurring

Another reason why a holistic approach to linear pay TV and streaming services makes sense is that for many consumers, it has become a holistic experience. It is all just watching TV on an app.

Historically, the pay TV and streaming consumer experiences were very different:

Pay TV was bundled and sold by a facilities-based provider, say Comcast or Verizon, which also often offered Internet and voice. Consumers accessed the programming through a dedicated set-top box, which had its own remote, its own custom UI and usually required changing the input on the TV. The programming itself was primarily scheduled shows and included ads. You paid for it separately, sometimes notified by a bill that came in the mail.

By contrast, streaming was generally sold as many, discrete apps, by many providers. All of these apps were accessible through a connected TV, such as a Roku or Apple TV. The programming was primarily on demand and ad-free. Usually, each charge showed up as a monthly line item on subscribers’ credit card statements.

Figure 9. Almost 1/4 of U.S. Pay TV Subs Get Service from vMVPDs

Source: MoffettNathanson.

These distinctions are now blurring. According to data from MoffettNathanson, almost 25% of pay TV subs purchase service from virtual MVPDs (vMVPDs), like YouTube TV, Hulu Live, etc., which are just apps on a connected TV (Figure 9). When you factor in the streaming apps offered by facilities-based providers (like Comcast’s Xfinity Stream or the DIRECTV app), perhaps as many as 1/3 of pay TV subscribers are accessing their pay TV service through an app. Also, a lot of the content offered by so-called linear networks is now on demand. At the same time, much of streaming is now ad-supported and, with the rising popularity of FAST, a growing proportion of it is linear, scheduled programming too.

Put differently, while the industry and investors draw a distinction between linear pay TV and streaming, many consumers no longer do.

For a lot of consumers, a bundle of pay TV and streaming services is a natural extension of how they watch TV.

Will Everyone Else Fall in Line Fast Enough?

So, there are reasons to think that a holistic bundling of pay TV and streaming could help improve the attractiveness and longevity of the lucrative pay TV business. The question is whether enough of the industry will co-operate.

As described above, one of the key reasons that TVE failed was lack of alignment within the industry. But things were different then. Most industry participants didn’t realize what was at stake. Today, the situation is far more acute. There are positive signs that (most of) the rest of the industry will fall in line:

Not surprisingly, since it drove the structure of its deal with Disney, Charter has been very clear that it intends to replicate this template with other programmers.

Disney probably has no choice but to offer other distributors similar terms owing to the MFN (most favored nation) clauses in many of its affiliate contracts.

WarnerBros. Discovery seems positively inclined. On its 3Q23 conference call, CEO David Zaslav said that the Disney-Charter deal “…created a, potentially, a very interesting bridge to more scale, lower churn and more stability to linear. We’ll have to see.” (WBD already provides Max to any pay TV subscriber who pays a distributor for HBO. It could effectively make Discovery+ the companion service for pay TV subscribers who don’t take HBO by adding more Turner content and bundle it with its basic cable nets in future affiliate negotiations.) And John Malone, who sits on the WBD board, was recently quoted as saying that he expects to see similar deals to the Charter-Disney structure because it reduced “the risk that everything gets blown up all at once.” “All media better figure out how to get together with old distribution and save each other’s ass or they’re all going to be in the frying pan.”

Paramount is a little more circumspect, but on the 3Q23 call CEO Bob Bakish noted that “if we go this direction with some partners…we think it could be an accretive development.”

AMC already includes AMC+ in its Charter deal and would presumably be open to doing so with other distributors.

Comcast is the biggest wild card. It formerly offered Peacock Premium for free to Xfinity customers, but started charging in June. A key part of its effort to reduce the losses at Peacock is converting those subscribers to paying. It will probably be reluctant to reverse course again, but if it pursues a similar deal to Charter and starts to bundle in third-party streaming services to its video subscribers, it may be hard not to follow suit with Peacock.

A Rare Ray of Hope

There has been growing acknowledgment in the industry that the TV business needs to “rebundle.” Six, seven or eight separate general entertainment streaming services simply isn’t economically sustainable.

The question is: who will be the bundler?

The media conglomerates are all leery of empowering Amazon, Apple or YouTube to rebundle TV for the obvious reasons.

To a lesser degree, subscale streamers may also be reluctant to license their streaming services to a larger competitor, like Disney.

Creating a consortium of media companies—Hulu v2.0—would also be challenging for all the reasons it was the first time, namely complex governance.

While not mutually exclusive with any of these options, enlisting the long-time cable, satellite and telco distributors to rebundle TV is an obvious solution. And it’s sitting right under the industry’s collective nose.

The most obvious candidates to “rebundle” TV are the current distributors.

It’s been hard to find much good news for big media companies lately. If the industry can coalesce around the Charter-Disney approach—admittedly, a big

”if”—there’s reason for optimism that it could help.

Throughout, I use the terms “linear” and “pay TV” interchangeably, although technically pay TV is a subset of linear, which also includes broadcast networks that are available for free over the air.

This is a great read

Thanks, very interesting. I think there is another reason for all those companies to put "all their eggs in the streaming basket", and it was the hope of finding more value in the "big data" than they finally seem to have been able to obtain, so far. I think it was a promise that has not been fulfilled.