The Year(s) Ahead in Media - Virtualization

The Hope for New Media Modalities and Tying it All Together

Note: This is the fourth and last post in a four-part series that discusses four tectonic trends (fragmentation, disintermediation, concentration and virtualization) that will determine the flow of value along the media value chain in coming years. Here are part 1, part 2 and part 3.

Tl;dr:

This concluding post discusses the fourth and last trend, virtualization, and ties the four trends together.

Virtualization refers to the steadily blurring lines between the physical and the virtual. This is the most hopeful trend for media overall, but also the most uncertain and furthest out.

As noted at the beginning of this series, value in media is stagnant and zero sum because time spent has plateaued.

The promise of virtualization is that as our lives become more virtual (and more digital), there will be new ways on interacting with media—new modalities—that increase time spent with media and/or the value consumers place on these experiences.

Associated technologies include those that enable new immersive experiences (XR and virtual worlds); more engaging experiences (fan creation and ownership); and new leisure time (AI efficiency gains and autonomous vehicles).

The most tangible of these is the Apple Vision Pro, which could eventually herald a new media software upgrade cycle, and, even further out, Level 4 self-driving, which could free up some commute time. But neither is likely to have a material effect for years.

The goal of this series was to look past the daily headlines and noise and explore the fundamental trends that will dictate how value is created and flows in media over the long term. Synthesizing them, we’re left with an industry in which value is stagnant over at least the near term, but the distribution of that value is not.

These dynamics are good for the most successful creators, who will have more bargaining power than ever, but not creators as a class. Both the good and the bad news is that the continued democratization of the content creation “stack” will make everyone a potential creator. The greatest hope for creators lies in better monetization tools and business models, not more equal popularity distributions.

For traditional intermediaries, all of these trends are just…bad. They will likely continue to lose consumption share, cede bargaining leverage to top talent, contend with stronger competitors and face riskier and less profitable businesses. A few technological lifelines are worth watching, but uncertain. They still have unique assets (audiences, IP, brands and, in some cases, data) and capabilities (like marketing prowess), but while the current is stronger in some media than others, almost all are swimming upstream.

The “new” intermediaries win, barring effective regulatory intervention (less likely) or technological disintermediation (crypto)/intermediation (AI agents). The prize, however, may be relatively small.

Consumers also win, with more choices than ever and, probably, lower prices. But they will pay in the form of potentially less “high quality” content and more decision fatigue, FOMO and dissatisfaction with the choices they make.

This is all fatalistic, but not nihilistic. The challenge for everyone in the value chain is to acknowledge the structural challenges and move ahead with purpose and optimism anyway.

4. Virtualization: The Blurring Distinction Between the Physical and Virtual

Of the four trends, this is the most hopeful for the media industry, but also the most uncertain and speculative.

In part 1, I noted that because time spent with media is already so high—for the average U.S. adult, 40% of the day and more than half of non-sleeping time—economic value in the broader media business will continue to be mostly a zero sum game unless people start to use media in fundamentally different ways. The obvious candidate to catalyze this change is, of course, technology.

Technology can taketh away. It is the engine of Schumpeter’s creative destruction and Christensen’s disruptive innovation. Over the last 20 years, it has upended the media industry for all the reasons I’ve discussed so far: it has lowered barriers to entry, changed consumers’ definition of quality, squeezed the traditional intermediaries and enabled unprecedented concentration of power and popularity.

It has giveth, too. It created new media channels (radio, film, TV, games); new storage and delivery formats (vinyl, cassettes, CDs, VHS, DVD); and new forms of media, like the relatively recent advent of social media and short-form video. All of that has expanded the time and dollar pie. For instance, consider again the chart that I showed in part 1 (re-pasted as Figure 27). While mobile cannibalized other devices, notably PCs, it also clearly increased overall media usage. Similarly, streaming rescued a moribund music industry (Figure 28).

Figure 27. Mobile Expanded the Pie

Source: eMarketer, April 2022.

Figure 28. Streaming Resuscitated the Music Business

Source: IFPI.

For media, the key question is whether there are new technologies that can create new ways of using media—new media modalities—that once again grow the pie? A few hold potential. The string that loosely binds them is that they all result from the further blurring of the distinction between the physical and the virtual/digital. Media, at this point, is almost entirely digital. At least superficially, it follows that the more our lives become digital, the greater the opportunity for media to occupy a larger role. As mentioned though, all of these are speculative in terms of timing, breadth of consumer adoption and the effect on consumer behavior.

The more our lives become digital, the greater the opportunity for media to occupy a larger role.

I don’t want this section to read like I prompted ChatGPT to write a few pages using as many technology buzzwords as possible. So, I’ll discuss the conceptual reasons for this technological evolution and why there is at least a glimmer of hope.

The Inevitable Blurring

The idea that our lives are becoming more virtual is very disquieting for a lot of people. At the beginning of the film version of Ready Player One, the camera pans across “The Stacks,” the trailer homes precariously stacked on top of each other where the protagonist lives, peering in as people wearing headsets prance around while jacked into a virtual world, escaping the dreariness of their real lives. Like Neuromancer, The Matrix, WALL-E, Snow Crash and a whole lot of other fictional depictions that merge the physical and the virtual, it’s meant to be dystopian.

In The Nature of Technology, Brian Arthur explains our unease:

“Our deepest hope as humans lies in technology; but our deepest trust lies in nature. These forces are like tectonic plates grinding inexorably into each other in one long, slow collision….We are moving from an era where machines enhanced the natural—speeded our movements, saved our sweat, stitched our clothing—to one that brings in technologies that resemble or replace the natural—genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, medical devices implanted in our bodies. As we learn to use these technologies, we are moving from using nature to intervening directly within nature. And so the story of this century will be about the clash between what technology offers and what we feel comfortable with.”

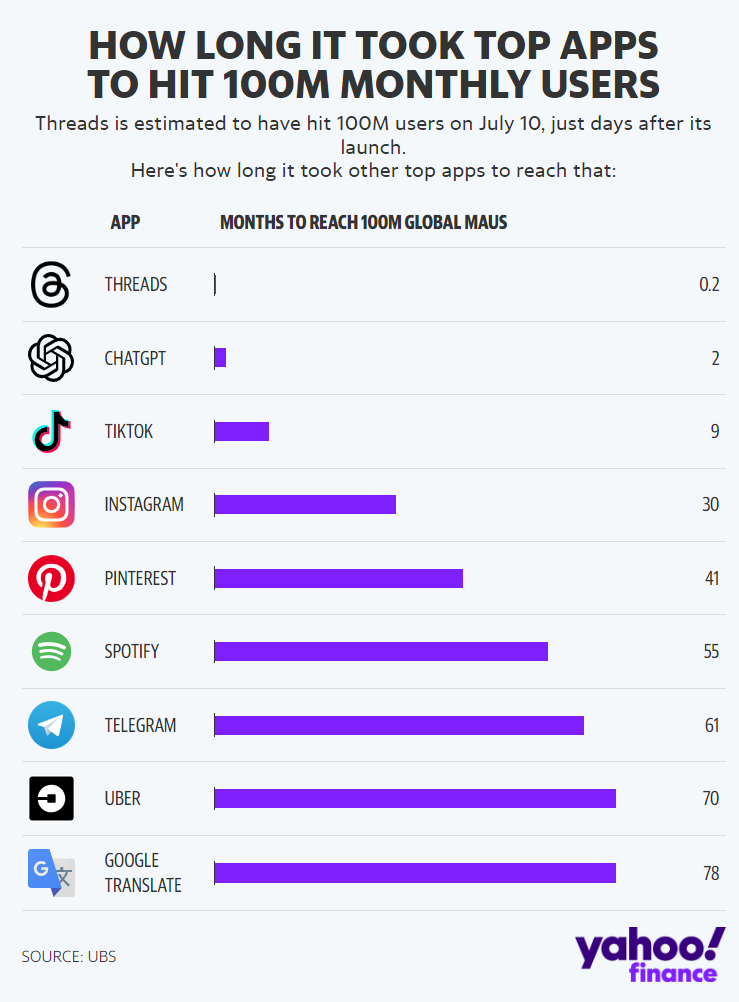

Misgivings aside, it’s hard to argue that anything stops the onward progression of technology. People may be leery of AI, but they also adopted ChatGPT faster than any other technology in history (Figure 29 — and Threads doesn’t count, since every Instagram account was signed up automatically).

Figure 29. ChatGPT Hit 100MM MAUs in Two Months

Plus, recent history shows that even deeply engrained social norms can change quickly when something more convenient comes around. It wasn’t so long ago that there was a stigma against working from home and online dating, you wouldn’t enter your credit card online and you’d never even think of getting in a stranger’s car (Figure 30). Those norms fell fast.

Figure 30. Social Norms Around Work From Home, Online Dating, eCommerce and Ridesharing All Changed Quickly

Sources: Becker Friedman Institute; Rosenfeld, Michael J., Reuben J. Thomas, and Sonia Hausen. 2023. How Couples Meet and Stay Together 2017-2020-2022. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Libraries; U.S. Census Bureau; FHV Base Aggregate Report and NYC Taxi & Limousine Commission, via Chartr.

New Media Modalities

I see three broad categories of potential new media “modalities:” more immersive experiences (extended reality and virtual worlds); more active forms of engagement with media (namely fan creation and ownership); and new pools of time that become accessible to media (AI generally and autonomous vehicles).

More Immersion

This includes both more immersive interfaces and more immersive online environments, or virtual worlds.

Extended Reality (XR). People have been talking about virtual reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR) and Mixed Reality (MR)—collectively, extended reality (XR)—as the “next big thing” for over a decade. It hasn’t happened yet for a whole bunch of reasons: headsets are expensive, lack of interoperability, lack of “killer apps” (other than gaming), uncomfortable headsets, motion sickness and so on. The big question this year is whether the Apple Vision Pro, which began shipping this month, will change that. At $3,500, it won’t be a mainstream product and Apple reportedly only expects to sell 400,000 in its first year. But, by all accounts, it’s a monumental achievement that exceeds the performance of any XR headset in the market. Plus, it’s Apple, which has a long history of being late to a category (music players, smartphones, tablets, smartwatches) and yet completely defining it.

Several have observed that the Vision Pro is primarily a media device. In the worst case, it’s just a new way to watch movies. In the best, it may become a new modality for consumption of entertainment in new ways, for which media owners could charge a premium. This may include content specifically made for these devices, like what Disney demo-ed at the Apple WWDC last year. It could also involve re-purposing existing content. Eventually it may be possible to use technologies like NeRF and Gaussian Splatting (and a whole lot of compute) to convert 2D film stock to 3D. This would enable viewers to “watch” a movie from any vantage point they want, even within the action itself. If successful, it could represent a new software upgrade cycle, like the CD or the DVD before it.

Virtual worlds. The “metaverse” has also been talked about as the next big thing for awhile, but still seems far off. Here’s Matthew Ball’s definition:

“The Metaverse is a massively scaled and interoperable network of real-time rendered 3D virtual worlds and environments which can be experienced synchronously and persistently by an effectively unlimited number of users with an individual sense of presence, and with continuity of data, such as identity, history, entitlements, objects, communications, and payments.”

Note this definition doesn’t specify the need for fancy headsets (or any interface, for that matter), but it’s still a high bar. In particular, interoperability, continuity and unlimited concurrent users are years away. The good news is that predecessors to the metaverse are already here: virtual worlds, like Roblox, Fortnite, Minecraft and even MMOGs like World of Warcraft. These have real usage: Roblox, the largest by usage, has 70 million daily active users (DAUs), engaging more than 2 1/2 hours per day. Average time spent on Fortnite is reportedly about 1 hour per day. These are primarily gaming platforms, but are also being used for other forms of communication, shopping, education and entertainment.

There’s not much evidence so far that virtual worlds, the predecessor to the “metaverse,” a big market for media outside of gaming.

The less good news is that it’s not obvious that these will become significant platforms for media consumption beyond gaming (other than an occasional big event, like the Fortnite Travis Scott concert more than three years ago). There’s also little evidence that virtual worlds represent large new markets for traditional media and entertainment brands. In Ready Player One, the OASIS metaverse included a lot of popular IP. In the real world, not so much. Roblox is almost entirely a UGC platform, where creators make the games. Fortnite maker Epic is also working hard to make Fortnite a creator-driven platform. Traditional media properties have a limited presence, other than some licensed music on Roblox or Marvel-branded skins on Fortnite. Disney’s recent investment in Epic is clearly aimed at established a beachhead in virtual worlds. Barring these kinds of concerted efforts, however, the jury’s out whether the “metaverse,” or any diminished version of it, is a large new opportunity for media consumption.

More Active Engagement

Technology may also enable more engaging and active ways of interacting with media, namely fan creation and ownership.

Fan creation. As I wrote in a post last year (IP as Platform), it’s clear that fans want to create using their favorite IP. Across media, the volume of fan creation is gated not by the desire to create, but by the accessibility of the medium. Written fanfic is the most accessible and is massive (with millions of fan fiction stories on sites like Archive of Our Own and Wattpad). Music is a little less accessible because it requires some musical ability, but TikTok and YouTube are full of song covers. Some types of game modding require coding ability, but even so it has become a cornerstone of the gaming business. Today most video game publishers enable it and some of the most popular games originated as mods (like PUBG, Dota and Counter-Strike).

Technology, including GenAI, should make more media more accessible. People with limited musical ability will be able to make remixes, collabs, mashups or videos of their favorite songs or artists. Complex types of modding will be more accessible to those with limited or no coding skills. And while video fan fiction has traditionally been extremely difficult and costly, it will become far more accessible too. A lot of the output from AI video generators, like Runway or Pika, are homages to established IP, like re-imaginings of movie trailers or animation styled after, say, Pixar or Studio Ghibli.

Traditionally, entertainment companies have vigorously protected their copyrights and prevented any commercialization of fan interpretations. Progressive media companies have an opportunity to make money from it.

Ownership. There’s still a lot of skepticism about anything crypto and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are often dismissively referred to as “pictures of monkeys.” Back before crypto winter set in, I wrote an essay called Every Media Company Needs an NFT Strategy-Now. (I was a little off about the “now” part.) In it, I argued why NFTs should not be thought of as digital art, but more broadly as digital property rights. The ability to confer provable ownership of unique digital assets could have two big benefits for media companies: 1) scarce digital collectibles would create another way to engage and monetize the biggest fans; and 2) because NFTs are saleable, they would provide fans a financial stake in their favorite IP, making them even more fanatical and more ardent evangelizers.

More Time

Perhaps the most promising outgrowth of new technologies is the opportunity to increase the available time spent for media.

AI. In 1930, John Maynard Keynes wrote an essay hypothesizing that “a hundred years hence” we would be working 15 hour work weeks. There is no consensus whether AI will destroy humanity, so, not surprisingly, there is also no consensus whether it will boost labor productivity. But there are good reasons to think it will (such as articulated in this article in Foreign Affairs and this Goldman Sachs report). In theory, at least, higher productivity could produce more leisure time. In practice, it will probably take well into the next decade (and past Keynes’ 100-year mark) to really understand the effects.

Even Level 4 self-driving could free up a big slug of time.

Autonomous vehicles. A more tangible, albeit not immediate, opportunity is the advent of autonomous vehicles. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the average round trip daily commute is now close to 1 hour. If freed up, that would represent a lot of time for media consumption. The consensus seems to be that true, “Level 5” (full self-driving under all conditions) commercially-available vehicles are at least a decade away, if not longer. But Level 4 self-driving in certain geographies and good weather conditions may be “doable” by 2030, potentially opening up a big chunk of time.

A (Faint) Glimmer

The arrow of technology points in a hopeful direction: toward more immersive (and potentially valuable) experiences, deeper engagement and perhaps even more leisure time. But what also jumps out from this discussion is that all of these potential benefits are years away and highly uncertain.

Tying it All Together

The goal of this series was to lay out the fundamental trends that will dictate how value is created and flows in media over the next several years. Let’s take stock.

Attention will continue to fragment as growth in the supply of content accelerates far faster than our ability to consume it and consumers’ definition of what warrants attention keeps evolving. As content approaches “infinite,” a few things will become relatively scarcer: attention, first-party data, curation, hits, fandom and community, brands and IP, marketing prowess and IRL experiences.

Technology will make it ever easier for creators to produce, market, distribute and monetize their work by themselves, reducing the bargaining power of traditional intermediaries.

As more consumption occurs on networks, the powerful positive feedback loops on these networks will continue to concentrate more power in the hands of a few platforms. This changes the competitive dynamic, both redefining the scale necessary to be relevant in media and entrenching recent entrants that have different profit motives. It also empowers new gatekeepers that are even more powerful than traditional intermediaries, but wield their power in different ways. Positive feedback loops will also continue to concentrate attention in a few hits, resulting in an increasingly skewed distribution of popularity. This will shift relative value to the head of the curve, hollow out the middle and increase the risk of making content.

Technologies that makes our lives more virtual (and therefore more digital) offer the distant and vague promise of increasing the amount of time consumers spend with media and the value they place on those experiences.

Synthesizing them, we’re left with an industry in which value is stagnant over at least the near term, but the distribution of that value is not.

Creators: Great for the few, not for the many

These trends are positive for a tiny proportion of individual creators, but not creators as a class. Owing to power law-like popularity distributions, the most successful (“A-list”) creators will be relatively more successful than ever. Well aware of their outsized importance, they (whether Taylor Swift or Taylor Sheridan) will also be able to extract an ever larger proportion of the economics. Journeyman creatives who subsisted on the middle of the content curve will come under pressure.

For creators, the hope is better monetization of the small audiences they can attract.

For creators overall, the good news is that everyone can now be a creator. Creators will have new ways to reach and monetize their audiences. And there is always a chance, however small, that some of this content might hit it big. The bad news is that everyone can now be a creator. The democratization of increasingly sophisticated tools along every part of the content “stack”—production, marketing, distribution and monetization—means that everyone will be empowered to create, re-create, remix and parody almost any type of content. The hope for creators is that these new tools and new business models will enable them to better monetize the audiences they attract—the realization of Kevin Kelly’s 1,000 True Fans. But power laws are merciless and the vast majority of creators will be relegated to obscurity.

Traditional intermediaries: Not much good news

Most of these trends are unequivocally negative for anything that could be called “traditional media.” Fragmentation of attention means a perennial shift of consumer attention to the “tail” of independent content and away from traditional channels and outlets. The waning bargaining power of traditional intermediaries translates to lost revenue and/or lower returns as creators circumvent them altogether or demand a larger share of the pie. The advent of GenAI may blur the quality and cost distinctions between creator and professionally-produced content, exacerbating both of these trends.

The concentration of market power in the hands of a few platforms means vastly bigger competitors who have very different profit motives. Power law-like popularity distributions means contending with superstar creators who have more leverage than ever; the death of the lucrative “middle,” which was a significant source of profits; and more variance of outcomes and therefore more risk. There is the potential of new media modalities that provide new ways to attract attention and monetize their IP, but it’s early days. So, the challenges are evident and immediate, the opportunities are unclear and further out.

For traditional intermediaries, the challenges are immediate and the opportunities distant.

All is not lost. The traditional intermediaries still control some of the most popular IP, they have recognizable consumer brands, sometimes they have valuable first party data, they are marketing/promotion machines and many creators will seek out the validation of working with the “establishment.” But they will likely need to adjust to smaller and less profitable businesses, a humbling and very difficult transition.

The “new” intermediaries: Winners of a skirmish

For the new intermediaries, barring regulatory intervention with real teeth (which seems unlikely), crypto riding in on a white horse or intermediation by AI agents, the trends are their friends. Falling entry barriers to creation means that more content will shift away from traditional distribution channels to their platforms and continued fragmentation of attention means consumption will follow. As they get bigger, network effects will make their competitive positions even more unassailable.

They also have massive advantages that position them to dominate media markets:

Control of unequaled troves of first party data will advantage their ad monetization, recommendation algorithms and ability to personalize experiences.

Huge R&D budgets and technological expertise (including, in some cases, their own proprietary foundational AI models and applications) will enable them to innovate new tools and products that attract a larger share of ad budgets and empower yet more creators.

Their massive financial capacity positions them to pick off traditional media assets, if they want them, should their owners come under duress.

In other words, they are positioned to win. But, relative to the size of their other businesses, the prize may be relatively small. As I noted in part 3, the market cap of the smallest of the platforms, Meta, is as big as the entire global media industry.

Consumers: More value, more fatigue, more distraction and more FOMO

As the amount of content keeps growing, value will flow to consumers in the form of more choice at low prices. Most of this “new” content will either be ad-supported, freemium or rolled into existing subscription platforms at no extra charge.

There will be cognitive and emotional costs, though. As consumers face ever more choice, they will also face more decision fatigue, their attention will be ever more divided and compromised and they will suffer the paradox of choice, namely less satisfaction with the choices they make. There is also a risk that the pressure on traditional media results in less “high quality”1 content.

Fatalistic, Not Nihilistic

If this all seems a little fatalistic, it is. The point was to lay out the trends that aren’t likely to change.

But fatalistic and nihilistic are different. Like death, taxes and life’s other inevitabilities, it kind of “is what it is.” For everyone operating in the media business today, the challenge is to acknowledge these trends and move forward with purpose and optimism anyway.

Here, I mean “high quality” as gauged by traditional measures of quality, namely big budgets and high production values.

Engrossing. A couple of thoughts (1) rates of consumers' tech adaptation. You observe past adaptation to major digital products, e.g. online dating, online credit card purchases. But as digital consumption products grow almost exponentially, this adaptation curve could change back earthwards or otherwise moderate (said as a boomer uninterested in digital saturation). Unplugging from the Matrix, in other words. (2) One of the impacts on the consumer is the availability of premium content at a reasonable price as the attention universe fragments. Your virtual reality future could accelerate this, meaning there will no longer be any reasonable price for those that want premium content, and we will pay unreasonable prices (or content piracy will skyrocket). We are already seeing this of course.