I often write that the last 10-15 years in video1 have been defined by the disruption of content distribution and the next 10 years are poised to be defined by the disruption of content creation.

Here’s the argument: The internet unbundled information from infrastructure and, with the help of a host of related technologies and massive infrastructure investment, caused the cost to move bits around to functionally head toward zero. We know what happened next.2 Now, there is another emerging general purpose technology, GenAI, that may send the cost to make bits to head toward zero, too.

This symmetry of falling costs to move bits and make bits sounds good. It’s pithy and memorable. It seems plausible. But still: it is admittedly very high level and hand wavy.

What will GenAI really mean in practice for the video business? Will the cost to make TV and movies truly “fall to zero?” Will two kids in a dorm room one day make the “next Avatar?” Or, is GenAI another flavor of Silicon Valley’s naïve technological determinism, a blind belief that technology always marches forward and anything that’s technically possible is inevitable, without regard to pesky inconveniences like law, regulations, ethics and consumer demand? And what does disruption mean, anyway? Are we talking about complete devastation, the Kodak-disrupted-by-digital-cameras kind of disruption, or the far more benign Marriot-disrupted-by-Airbnb kind of disruption?

Figure 1. Two “Victims” of Disruption

The only credible answer to these questions is: no one knows. That doesn’t mean we’re completely flying blind though. We can frame out a range of possible outcomes by using scenarios.

Tl;dr:

Scenario planning is a useful tool for navigating uncertainty. It can help identify the range of possible outcomes, the key milestones to watch, and the potential implications.

A key step is identifying the two critical variables that will determine possible future states and the extreme potential outcomes for each. Below, I use technology development and consumer acceptance to construct a scenario matrix and analyze the possible state and implications of AI video in 2030.

The possible outcomes for technology development range, at one extreme, from AI video models stalling out at their current capabilities to, at the other, completely resolving their current limitations in realism (especially the “uncanny valley”), audio-visual sync (especially lips), understanding real-world physics, and fine-grained creative control.

The possible outcomes for consumer acceptance range from skepticism and sometimes outright hostility to fully embracing AI (and actually preferring it for some use cases). Steps along the way include consumers accepting it for certain content genres and use cases, especially those that don’t rely on emotive humans.

Varying each of these variables between their extremes produces a 2 x 2 with four scenarios: low tech development, low consumer acceptance (“Novelty and Niche”); high tech development, low consumer acceptance (“The Wary Consumer”); low tech development, high consumer acceptance (“Stuck in the Valley”); and high tech development, high consumer acceptance (“Hollywood Horror Show”).

Writing out narratives for each scenario is the most instructive part, because it helps make the abstract more concrete.

Reality will probably fall somewhere in between, but this shows why it won’t require the most radical scenarios for the video business to change radically.

How Scenarios Work

One of the most useful tools for operating in an uncertain environment is a scenario planning matrix. This entails identifying the two most important variables, determining the polar extreme outcomes for these variables over a given time period, and constructing a 2 x 2 matrix that produces four potential future state scenarios. The most instructive part is writing a narrative describing each of these scenarios. Think of these narratives like news articles from alternate futures, explaining how we got to that (possible) future state.

The scenarios are extreme, so reality will probably fall somewhere between them. But the exercise helps define the bounds of what will probably unfold; the signposts that would indicate we are heading in one direction or another; and the potential implications of different outcomes. It also helps make abstract problems feel a bit more concrete, especially when the scenarios are specific.

A Brief Digression: What I Mean by “GenAI Video”

Before getting into the scenarios, it would probably be a good idea to explain what I mean by “GenAI video” (or “AI video,” which I use interchangeably). I am referring to AI video tools that augment and streamline human creativity, NOT fully-autonomous AI-generated video.

Sometimes, “AI video” is considered synonymous with “zero-shot AI video,” namely that you put in a prompt and a fully-realized movie comes out. Other times, it even means “fully autonomous storytelling,” where an AI writes, directs and produces film completely independently. I think both are unlikely to produce anything watchable anytime soon, if ever. But more to the point, this capability depends more on the evolution of LLMs and multimodal AI than on AI video models.

By “AI video,” I mean tools that augment, enhance and streamline human creativity, not replace it.

Throughout this analysis, I assume that GenAI video will require significant human oversight and judgment for the foreseeable future. So, I am referring to tools, like AI video models (and AI audio models, workflow tools, etc.), that empower people to make high-quality video faster and cheaper. This might involve delegating some creative decisions to AI, but by no means all or even most of them.

With that out of the way, let’s get to the scenarios.

Identifying the Two Key Variables

There are a lot of unknowns about how GenAI video will evolve. Here’s a partial list:

How will regulators, the courts or the market resolve issues around copyright infringement and IP rights? Will regulators or consumers require AI content labeling?

Will there emerge even more performant architectures, beyond transformers and diffusion models?

Is there room for so many competing proprietary GenAI models (Sora, Veo, Kling, Minimax, Runway, Pika, Krea, Luma, etc.)? Will they carve out niches, in which some are better for certain applications? How big is the TAM? Will they solely appeal to enterprise and prosumer or are they mass consumer products? What is the competitive advantage in these models? Data? Compute? Architecture? Will proprietary or open-source models prevail?

What is the true cost of operating these models? Will they need to be run in expensive data centers or will local devices suffice?

How much will GenAI really reduce costs for traditional video production workflows? Will it replace jobs? Which ones?

Will consumers accept GenAI and for which use cases? For which content genres?

Will GenAI ever cross the “uncanny valley” and produce synthetic people that are indistinguishable from live footage?

Will Hollywood studios adopt it? Creatives? Creators? Will an AI-enabled film ever win critical praise or even an industry award?

How will fine-grained control evolve? Will models eventually replicate (or surpass) anything that can be done with a camera and professional lighting? Or will using AI always necessitate a tradeoff with creative control?

Will “world models” enable GenAI to simulate complex real-world physics?

And you could tack on another question at the end of each of these:

If so, when?

That’s a lot of things we don’t know. For our exercise, we need to distill them into two critical variables and determine the range of potential outcomes for each. (In our case, our time frame is in 2030, out five years.)

Looking at this list, we can group most of these unknowns into four categories: technology development, consumer acceptance, legal/regulatory and economics/business models. The latter two are clearly important. Hollywood won’t adopt GenAI without legal clarity. Economics will determine the size and distribution of profit pools.

But since we can only choose two, let’s go with what I think are the biggest unknowns: technology development and consumer adoption.

Technology Development

AI video models have improved tremendously in the last two years. Below is the iconic and disturbing Will Smith-eating-spaghetti video, made with Stable Diffusion in April 2023. Compare it to the Veo2 compilation demo from Google or a recent video made using Sora by Chad Nelson from OpenAI.

This pace of improvement in less than two years is startling. But they aren’t perfect yet.

AI video models don’t pass the “video Turing Test,” at least not yet.

In 1950, Alan Turing introduced the so-called Turing Test (originally called “the imitation game”), meant to test whether a machine could fool a human into believing it is communicating with another human. Turing didn’t conceive of different tests for different modalities, but let’s propose a “video Turing test,” to test whether a human would believe AI video was generated or live action. AI video models don’t currently pass the video Turing Test.

There are a few areas they can still improve:

Realism (especially the “uncanny valley”). If you look again at the Veo2 demo, it’s hard to tell that both of the women (the DJ and the doctor) aren’t real. We’re getting very close to passing the so-called “uncanny valley,” but it’s a high bar. Humans are highly sensitized to the most subtle changes in human faces even before we can speak (think of an infant staring at her mother’s face). Note that the Veo and Sora demos feature relatively quick cuts, so the people don’t convey much change in emotion.

Audio-visual sync. Also notice that no one is talking in either demo. Runway now offers Lip Sync and the open-source tool Live Portrait makes it possible to sync facial movements between a reference video and a generated video, including lip sync. However, in both cases it is clearly noticeable. It isn’t there yet.

Resolution and clip length. These are almost solved. Veo2 is in closed beta, but it claims to enable up to 4K resolution and clips as long as 1 minute. There has also been rapid development in upscaling technologies that can increase resolution (such as from Topaz and Nvidia). 4K is suitable for all but the largest format screens, like Imax, or very VFX-heavy films. And most shots in TV shows and films are just a few seconds, other than an occasional long take, so 1 minute is more than enough.

Physics/temporal coherence. Despite the impressive realism in the demos above, these models still struggle with complex dynamics, especially involving multiple objects or actors. They have been trained on video, which is an abstraction of the real world, so they do not yet understand the real world. Despite occasional breathless claims to the contrary, they don’t contain sophisticated “world models” or physics engines. (There are early efforts underway to fix that, such as Runway’s research on general world models or World Labs, co-founded by Fei Fei Li.) My “model buster” prompt is “A man in a smoky pool hall, breaking a rack of balls.” No model has figured it out yet.

Fine-grained control. Initially, GenAI video models were like slot machines—you put in a prompt and held your breath. Over time, they have been progressively adding finer-grained control (something I discussed in detail in Is GenAI a Sustaining or Disruptive Innovation in Hollywood?). Last week, Hailuo, creator of Minimax, introduced the T2V-01-Director Model, which enables more sophisticated camera controls, as shown in the embedded video below. At around the 0:30 mark, see how the shot faithfully follows the complex set of instructions “first, truck left, tracking shot, then pull out, and end on a vehicle POV.” Models are learning better controls through a combination of pre-labeling video clips (e.g., including metadata about the camera motion, like “shake camera slightly”, “tilt up,” “truck left,” in the training data) and “manipulation in the latent space.” The latter means that the model learns which parameters correspond to different visual outcomes, so that it is possible to influence the generation process during inference. In theory, with enough training data and metadata, it will be possible to offer ever-finer grained control.

Recall that our goal is to identify the continuum of possibilities for how GenAI technology will develop by 2030. At one extreme is the current state, which assumes that the technology won’t improve from here. The other extreme is the idealized future state for each of the features described above, meaning that each of these limitations is eventually solved. This continuum is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Continuum of Potential Technology Development

Source: Author.

Consumer Adoption

The other critical variable is the degree to which consumers will accept AI. So far, the jury is out.

There has been some backlash to the use of AI, especially when not disclosed beforehand, such as Disney’s use of AI to generate the opening credits of Secret Invasion; the use of AI for a few still images in Late Night with the Devil; or, most recently, the use of AI for voice enhancement in The Brutalist and Emilia Perez. However, it isn’t that simple. The issue here seems to be whether or not filmmakers were upfront about it; no one seemed to care when AI was used for de-aging in The Irishman, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny or Here. Also, it isn’t clear that the public cares as much as the industry.

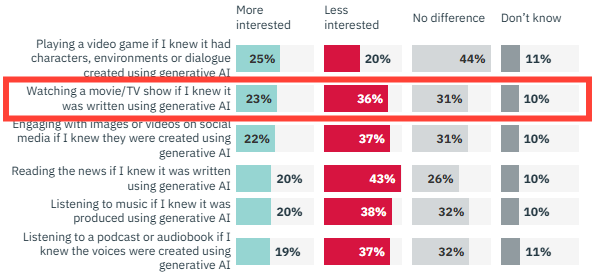

A recent survey from HarrisX and Variety VIP+ found that consumers’ willingness to engage with AI-enabled content varies (Figure 3). As shown, when asked about their interest in watching a movie or TV show written using GenAI, 10% said they didn’t have an opinion, and, of the remaining 90%, 54% were indifferent or more interested in GenAI content. Plus, receptivity seems correlated with familiarity. Variety noted that those who “report regularly using gen AI tools are also more likely to feel positively toward the use of AI-generated material in varied types of media content, according to recent FTI Delta survey data shared with VIP+.”

Figure 3. Consumer Receptivity to AI-Generated Content Varies

Source: HarrisX, Variety VIP+, May 2024, N=1,001 U.S. Adults

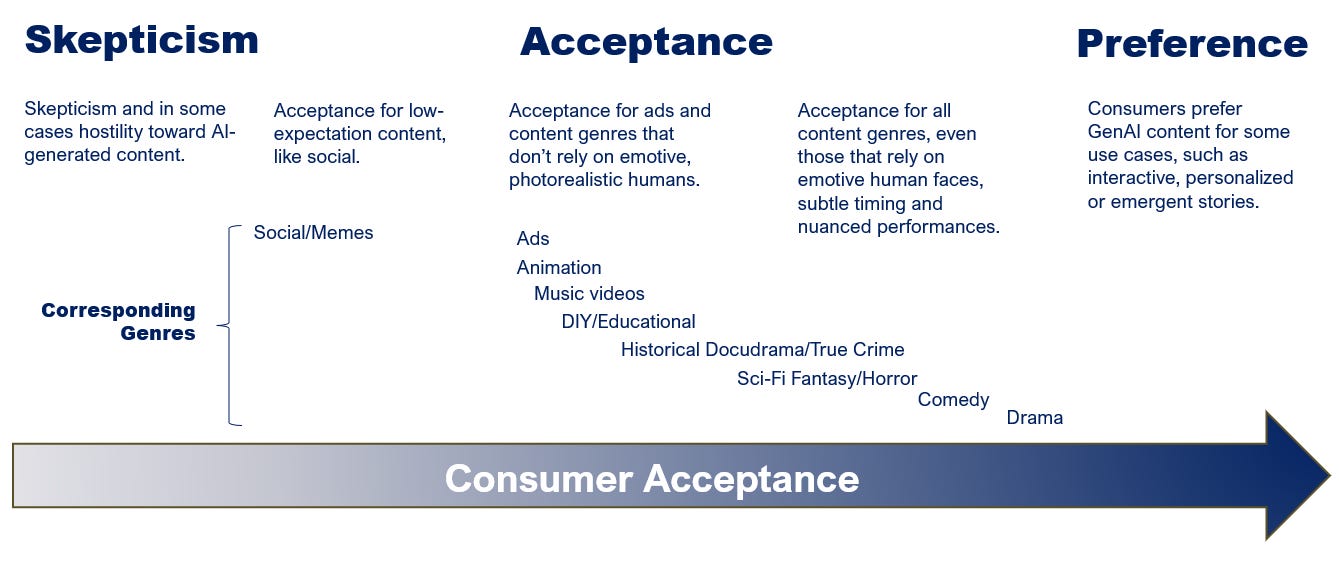

For our purposes, it is possible to imagine a continuum of consumer acceptance that looks like Figure 4.

This continuum progresses from the current high-degree of skepticism and sometimes hostility; to acceptance in low-stakes, low-expectation content, like social video, memes, etc.; to progressively accepting AI in different genres, depending on that genre’s reliance on emotive human faces, starting with ads and animation, then music videos, educational, historic re-enactment/true crime/docudrama, then maybe sci-fi and horror (especially in which humans are heavily doctored), and, the final frontier would be comedies and dramas that require subtle timing, nuanced performances and a wide emotional range; and the most extreme outcome would be that consumers come to prefer AI-generated content for certain use cases, especially those that GenAI is uniquely suited to do, like personalized, interactive and emergent stories.

Figure 4. The Continuum of Potential Consumer Acceptance

Source: Author.

The Scenarios

Having defined our ranges for the two key variables, the next step is to construct the potential future states in 2030. For now, let’s not judge the likelihood of each. We’ll get to that in a moment.

Figure 5. The Four Scenarios

Source: Author.

The four scenarios are shown in Figure 5. Starting from the lower left and moving clockwise, we have low technology development and low consumer acceptance, or what I named Novelty and Niche; high tech development and low consumer acceptance, or The Wary Consumer; high tech development and high consumer acceptance, or Hollywood Horror Show; and low tech development and high consumer acceptance, or Stuck in the Valley.

Below, I write out a narrative for each.

“Novelty and Niche” (low tech development, low consumer acceptance)

This is more or less the status quo. The technology doesn’t evolve a lot from here and consumers view AI video as a novelty good for a limited range of use cases, like memes, social video, simple animation and maybe music videos.

The tech stalls out and consumers aren’t interested anyway.

In Hollywood, by 2030 AI still isn’t used much in final frame, other than for some environments, establishing shots and digital re-shoots. It is mostly used in pre-production—for previsualization, script writing assistance, script coverage, and concept art—and in post production—like localization services in smaller markets, some VFX automation, first pass edit, de-aging and voice synthesis. Studios have used these technologies to marginally reduce production costs, say 15-25%.

AI is regarded largely as a novelty and a sustaining innovation, but hasn’t changed the business much. Current trends (cord cutting, growth in streaming, shift of time and attention to creator content, etc.) have continued at a steady, linear pace.

“The Wary Consumer” (high tech development, low consumer acceptance)

Here, AI can produce visuals that are nearly indistinguishable from live action and has leapt over the uncanny valley. Blockbuster-quality films could theoretically be made entirely synthetically, using synthetic actors and sets. But consumers aren’t having it.

Unions and regulators have pushed for strict controls and disclosure of any AI usage. Consumers view AI as fake, cheap, and ethically dubious. Again, it is considered suitable only for a narrow range of use cases, this time constrained by public opinion, not technology. It is used in the same kinds of applications as in the “Novelty and Niche” scenario: memes, social video, music videos, perhaps some educational or factual content where there is no perceived need for human authorship or authenticity. Even animated programming that uses AI is considered creepy and parents shun it.

AI can create high fidelity visuals that are indistinguishable from live action, but the public won’t have it.

Hollywood could do more, but is constrained by public pressure and the stance of talent. In the production process, AI is again relegated to behind-the-scenes, mostly pre- and post-production. For well-known creatives, the prospect of making projects at a fraction of the cost of traditional production and ending their reliance on big studios is appealing. But they steer clear of AI, fearful of both public backlash and being ostracized by the rest of the creative community. Emerging creators try to leverage AI to break into the industry, but most of the public rejects these efforts.

The current dynamics in media continue, including consumers continuing to shift their time and attention to creator media. But they still spend a lot of time and money on the biggest blockbusters and premium TV shows. Hollywood retains its lock on high-production value content and the relatively small oligopoly among the biggest media conglomerates and a few big tech companies stays intact, other than perhaps some consolidation here and there.

“Stuck in the Valley” (low tech development, high consumer acceptance)

In this scenario, consumers embrace AI, but the technology doesn’t keep pace.

Consumers think GenAI is cool, especially some of its unique attributes, like being able to generate personalized, interactive and emergent stories in real time. They also like using GenAI for fan creation, making memes, parodies and fan films about their favorite IP.

Consumers want it, but the technology can’t deliver.

The technology hasn’t improved much from the current state, never achieving realistic humans and still struggling with complex physics. However, GenAI is used extensively in advertising, animated content, DIY/educational, historical/docudrama/true crime and even some sci-fi, fantasy and horror movies and shows.

Creators also work within its constraints to create a tsunami of new content, most unwatchable, but some intriguing and some compelling. To cite a statistic I use all the time: by my estimate, Hollywood put out about 15,000 hours of film and TV shows in 2024 (a generous estimate, by the way) vs. about the 300,000,000 hours of creator content uploaded to YouTube. At the same time, consumers’ definition of quality continues to shift away from high production values. By 2030, very little of this new content is considered good, but only an tiny proportion needs to be competitive with Hollywood to upend the supply/demand balance. Keep in mind that 0.01% (1/100 of a percent) of 300,000,000 hours is 30,000 hours—twice what Hollywood produces per year.

By 2030, YouTube’s share of TV viewing surpasses 20%, up from 11% today. Consumers have enough “good enough” content available for free on YouTube and other online platforms that in recent years they have started to cancel streaming services; by the end of this decade, the average number of streaming services per streaming home has slipped, falling from 4 to 3. The have/have not divide in Hollywood widens, as subscale monoline video companies are consolidated into larger multi-line business as it becomes clearer that corporate video is no longer a profit center for most.

“Hollywood Horror Show” (high tech development, high consumer acceptance)

In this scenario, both technological development and consumer acceptance continue to increase. GenAI video is virtually indistinguishable from anything shot with a camera. Consumers aren’t phased by dramas starring synthetic people and are embracing some of the unique capabilities of GenAI video described before.

The cost to produce video converges with the cost of compute; the below-the-line cost (i.e., non-talent production costs) of a blockbuster-quality film falls from $1-2 million per minute today to $10-20 per minute. There is a near infinite supply of high production value content. Just as there are one-author books and one-artist albums, we have one-artist feature length movies and shows. There are virtually no barriers to high-quality content creation—competition comes from everywhere, including the near infinite pool of independent creators, and is global. Demand for U.S. content falls internationally as the production values and volume of local content increases.

Infinite content meets finite demand, completely altering the economics of video creation.

Content and culture atomize further along a continuum of experiences, reflecting the tension between the need for individual and shared experiences. These range from personalized content to micro-communities, subcultures, sub-mass and mass cultural experiences, but the last category are few and far between.

Infinite supply meets finite demand. The economic model of content creation shifts radically, as video becomes a loss leader to drive value elsewhere—whether data capture, hardware purchases, live events, merchandise, fan creation or who knows what else. The value of curation, distribution chokepoints, brands, recognizable IP, community building, 360-degree monetization, marketing muscle and know-how all go up.

Hollywood looks nothing like it does today.

Placing Some Bets

These scenarios range from incremental change to radical transformation. Before, I wrote that we should hold off judging their likelihood. Let’s now turn to that.

The most conservative scenario, namely that the current state persists, seems highly unlikely. The question is where we settle out among the others.

Technology Will Surely Advance, But How Much?

The concept that GenAI technology will stall out here defies all logic and recent experience—especially in light of the amazing advances in just the past two years, the resources being thrown at it, and the practice in the AI community of sharing many breakthroughs.

So, we know it will keep getting better, but how much and how fast? I’m not sure anyone knows and I certainly don’t. Here are a few things we do know:

Training Data Will Likely Grow

Unlike LLMs, which have apparently scraped nearly all the text on the internet, a lot of video footage is still inaccessible to AI video models. With more data, they will get better.

So far, Hollywood studios have been reluctant to license their libraries for training. However, the models need a large volume of hours more than they need specific libraries or IP. My guess is that owners of smaller libraries, who are less worried about the blowback from talent, public relations or (perhaps) the long-term strategic implications, will be more willing to license training rights. If large studios see that the window is closing to license their rights, some may follow suit. This could prove enough.

Fine-Grained Control Will Improve

There is a lot of effort underway here currently. These include fine-tuning models to enable very specific camera controls (using more efficient, LoRA-based approaches), more research into manipulating parameters in the inference process and creating larger labeled datasets in pre-training.

AI Will Probably Achieve a Better Understanding of Physics, Not Only for Video

Most GenAI models are trained on abstractions of reality, as I alluded to above. LLMs are trained on text (which is an abstraction of an abstraction; it is an abstraction of language, which is an abstraction of thought); video models are trained on pixels; audio models are trained on digitally-sampled notes, etc. They are not trained on the real world.

The next frontier of AI will require a better understanding of real-world physics and video models would benefit.

As also mentioned above, there are currently efforts underway to address this deficiency by creating “world models,” some of which rely on some sort of physical embodiment. These kinds of models are needed for more than just more lifelike video. The next frontier in AI is real-world applications: autonomous vehicles and robots. For these to succeed, it will be necessary for AI to develop a better understanding of the physical world, including all its many edge cases. So, these efforts are pursuing a much bigger prize than the payoff of achieving temporal coherence in a video model, but video models should be among the beneficiaries.

Brains Want to Interpolate

The bar for realistic video may be lower than commonly believed.

Human brains are very good at interpolating. Vision in particular is heavily constructed, not just perceived. Many studies (like this one) have shown that most of the input to the visual cortex comes from our own internal models of the world, not sensory input from our eyes. (We also have a blind spot where our optic nerves connect to our retinas, but we don’t see it because our brain fills in the gap.) We actively seek to create cohesive images from limited information. That’s why minimalist and abstract art can be highly evocative even with a few brushstrokes or lines.

AI models don’t need to be perfect.

The implication is that AI video models don’t need to have perfect, frame-by-frame photorealism. They only to need to provide the right cues for the brain to fill in the rest. Where they currently fall short is when those cues are confusing or discordant.

There is No Technical Reason the Uncanny Valley Can’t be Vaulted

While our biology is cooperative in some areas, in others it is not. As mentioned before, the uncanny valley is a very high bar, because we’re so attuned to nuanced facial expressions. Nevertheless, there is no technical reason AI can’t overcome this challenge.

Following on the prior points, all video is an abstraction of reality. It comprises frames moving past at the rate of 24 or 30 per second. These frames comprise pixels. And what are pixels? They are just a color value that is captured by a lens, converted to numbers, converted to bits, and then converted back to a color value.3

So, when you watch iShowSpeed or Stranger Things or Downton Abbey or The Kardashians or NBC Nightly News with Lester Holt or any other real people, doing real-people things, everything you are watching is just pixels, no different than the pixels produced by an AI model. Technically, video of synthetic people can be literally indistinguishable from video of real people.

There is no technical reason that synthetic people can’t be literally indistinguishable from real people.

And we’re getting closer. As mentioned above, it is already hard to tell that the people in the Veo demo aren’t real. This mirrors the amazing improvement in image generation models over the last couple of years; Figure 6 shows the same prompt used in each generation of Midjourney, up through the most recent.

Will AI ever surpass the uncanny valley? Right now, it’s impossible to know, but it will likely keep improving. The ability to capture more nuanced emotions and lip syncing will almost certainly get better, owing to larger datasets, better markerless motion capture (when using reference video) and multi-modal model architectures that are better able to handle multiple data streams (like transformers that have both visual and audio attention mechanisms).

Figure 6. Progression in Midjourney

Source: Rinko Kawauchi, prompt “high quality photograph of a young Japanese woman smiling, backlighting, natural pale light, film camera.”

Consumers Will Probably Warm to AI—To a Degree

I think that the trajectory of consumer acceptance of AI is a bigger wildcard than the technology.

AI is unsettling. Here’s a quote from Brian Arthur in The Nature of Technology that I’ve cited before, which I think captures it:

Our deepest hope as humans lies in technology; but our deepest trust lies in nature. These forces are like tectonic plates grinding inexorably into each other in one long, slow collision....We are moving from an era where machines enhanced the natural—speeded our movements, saved our sweat, stitched our clothing—to one that brings in technologies that resemble or replace the natural—genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, medical devices implanted in our bodies. As we learn to use these technologies, we are moving from using nature to intervening directly within nature. And so the story of this century will be about the clash between what technology offers and what we feel comfortable with.

Most depictions of AI in popular culture reflect this unease. From HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey, to Skynet in Terminator, to M3GAN, AI is usually something to be feared or distrusted. It’s not surprising that people would be disconcerted by content created with AI. Will they get over this hump? Here’s how I think about it:

TV and Film Keeps Getting More Synthetic and Consumers Haven’t Revolted Yet

Filmmaking has always involved a social contract between viewer and filmmaker: “I will suspend my disbelief that this is fake as long as it’s sufficiently believable. But I know it’s fake.” From AI Use Cases in Hollywood:

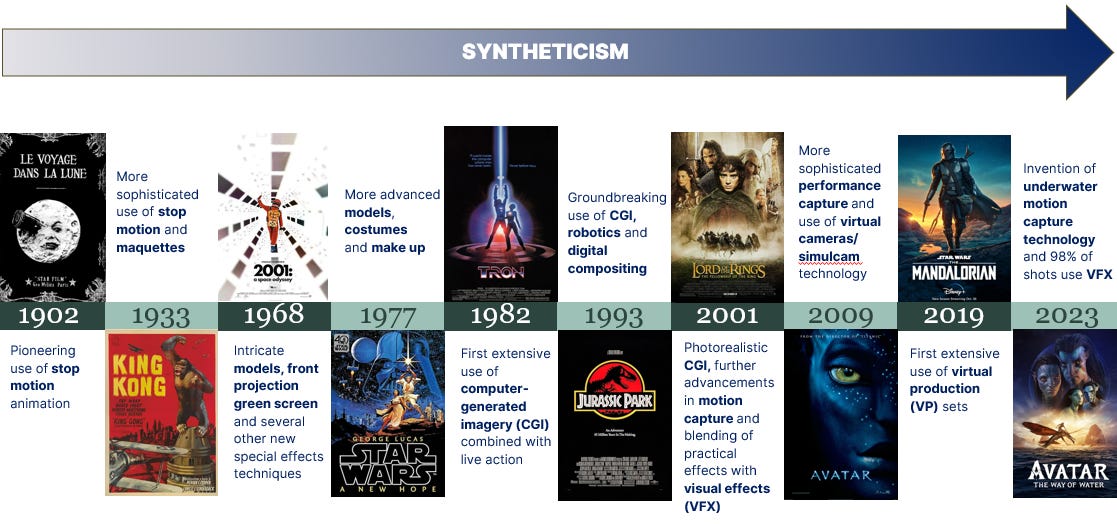

You can draw a line from George Méliès using stop motion animation in A Trip to the Moon (1902) to the intricate sets in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) to the maquettes in King Kong (1933) to the even more sophisticated models, costumes and make up in Star Wars (1977) to the first CGI in TRON (1982) and the continuing evolution of computer graphics and VFX in Jurassic Park (1993), the Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001) and Avatar (2009), to where we are today. Every step has become more divorced from reality…[T]oday almost every mainstream film has some VFX and, in a film like Avatar 2: Way of Water, almost every frame has been heavily altered and manipulated digitally.

This history of syntheticization is pictured in Figure 7. Note that, until the advent of CGI in the early 1980s, most of the innovation in syntheticization consisted of adding synthetic physical elements (maquettes, prosthetics, physical special effects, etc.); after that, most of it consisted of adding synthetic virtual elements, created on a computer. But consumers have continued to eat it up, even as films and TV shows have become increasingly VFX-heavy.

Figure 7: The History of Filmmaking as a Process of Syntheticization

Source: Author.

So, the question then is: Is there something about the “fakeness” of AI that is inherently more off-putting than the “fakeness” of VFX? I think the answer is no. I believe that the problem to date has been unnatural humans, janky motion, temporal inconsistency and temporal incoherency — things that have just looked “off.” But if these are sufficiently resolved, I don’t expect that consumers will reject AI just because it is AI.

Is there something about the “fakeness” of AI that is inherently more off-putting than the “fakeness” of VFX, which consumers have embraced?

The Lines Between AI and Not-AI Will Blur

It will also get harder to tell what is AI and what isn’t. AI will increasingly be incorporated in popular edit suites, native AI like Adobe Firefly or 3rd party plug-ins. Workflows will increasingly entail some combination of live footage, AI enhancement or augmentation, AI-assisted editing, manual cleanup, etc. At that point, who will know what is and isn’t AI in the final product?

Familiarity Will Probably Breed Acceptance

The FTI Delta study mentioned above concluded that consumers are more receptive to AI when they’ve used the tools. That follows a general truism: people like things (and, for that matter, people) more when they’re more familiar with them. Right now, AI is scary partly because it’s mysterious. As the mystery fades, reluctance probably will too.

It Doesn’t Require Radical Scenarios to Produce Radical Outcomes

A lot of people in Hollywood don’t want to engage on this topic. I think they should.

Part of the problem is that we tend to think linearly, even though the world isn’t linear. So, it can be very hard to see inflection points, even when you’re standing right in front of them. It reminds me of this cartoon from Wait But Why:

Figure 7. It’s Hard to See Inflection Points, Even When They’re Right Next to You

Source: Wait But Why.

Another challenge is that it’s easy to dismiss a risk that seems so abstract. A few months ago, I was talking with a Hollywood executive about GenAI and he shrugged his shoulders and said “Yeah, no one knows.” The point of this scenario exercise is to make the abstract more concrete and force us to confront what might happen.

For the reasons described above, it is hardly imaginable that GenAI technology won’t keep progressing. Maybe it will never be entirely indistinguishable from live action footage, but it will get closer. It’s also hard (albeit not as hard), to imagine that consumers won’t warm to GenAI-enabled content over time. Perhaps we’ll never fully accept synthetic humans, but there are a lot of content genres and use cases that don’t rely on emotive actors. So, the most likely outcomes probably fall somewhere in the messy blob in Figure 8.

Figure 8. The Messy Blob of Likelihood

Source: Author.

What does that tell us? Even short of the most radical scenarios, the business would transform radically. Among other things, within that blob:

There would be a vast increase in the supply of content, especially in certain genres.

Consumer time and attention would continue to get drawn away from corporate content, perhaps everything other than the most premium blockbusters and scripted TV.

Barriers would fall for small teams, creators and international producers who are willing and able to work within the constraints of technology and consumer preferences.

As production costs fall, new revenue and distribution models would likely emerge.

As content becomes more abundant, other things would get scarcer and more valuable as consumers seek out both filters to navigate all that choice and human connection. These include curation, trusted IP and brands, marketing prowess, communities, provenance, and IRL events.

In Figure 7, you can’t tell which way the little guy is facing. Today, a lot of people in Hollywood are looking backwards, assuming or hoping the slope won’t change much. It probably will.

Thanks for Mike Gioia for his feedback on a draft of this post.

And, for that matter, media broadly.

For the sake of completeness: Entry barriers fell, paving the way for new entrants like Netflix, Amazon and YouTube. They have radically changed the consumer video experience and the economics of the video business. This has exerted tremendous pressure on the incumbent video value chain, including media conglomerates, cable and satellite video distributors, TV stations, and movie theaters, and ripple effects have been felt everywhere else, including advertisers, ad agencies, sports leagues, talent, and talent representation.

Each pixel is usually made up of three subpixels, that emit different colors: red, green, and blue (RGB). In an 8-bit system, each of these subpixels could have any of 256 values (two possible values for each bit raised to the 8th power = 256). So, that means that each pixel can take on one of 16.8 million values (256 x 256 x 256)—in other words, virtually any color the human eye can see. In an HD signal, there are over 2 million pixels per frame; a 4K image has four-times as many, or more than 8 million.

Thank you so much, what a great and solid analysis! Beats 99,9% of my linkedin feed for sure.

I'm in the advertising film business, and there's 2 things I can already tell:

1) your second factor - audience acceptance - is irrelevant in our ecosystem as long as the quality is good enough, which it obviously already is. The 100% ai generated COKE xmas commercials were tested with audiences and people loved them, no pushback there.

2) "Studios have used these technologies to marginally reduce production costs, say 15-25%." That does not seem "marginal" to me! As we pitch each&every project against at least 2 competitors, a 20% cost advantage is a MASSIVE business advantage over the competition. I wish we could harness AI's potential to be 20% less costly than the competition (but then again, if we can, then the competition also can).

For now, these cost cutting advantages have not arrived in our ecosystem. I assume that is to a large extent based on legal uncertainties around the use of AI, and will soon change drastically once the legal frameworks get adjusted to what's technically achievable.

It is not true to say that people have enough video content available “for free” on YouTube: we either pay a subscription fee or have to watch a huge amount of video ads. This means it has to be rewarding anyhow. We might be open to spend 2 or 3 minutes watching entirely AI generated video while the technology behind is surprising, but eventually we’ll not care about how that video was made and enjoy it for its content: the story, the characters, the setting, etc. So, I believe people will eventually accept video AI except when the characters matter. Otherwise, it feels like an animation movie and these are set apart even without the involvement of AI at all.