How Will the “Disruption” of Hollywood Play Out?

A Framework for Thinking Through the Speed and Extent of Disruption Shows Hollywood’s Vulnerability

[Note that this essay was originally published on Medium]

Six months ago, I wrote an essay titled Forget Peak TV, Here Comes Infinite TV. It laid out the case for why four technologies, most notably virtual production and AI, are poised to democratize high quality video content creation over the next 5–10 years. The main conclusion was that — just as the past decade in the TV and film business has been defined by the disruption of content distribution — the next decade will be defined by the disruption of content creation.

When I wrote it, I was a little concerned that the concept was so far out that it would be considered too theoretical and irrelevant. But a lot has happened since then: there has been an onslaught of new AI-enabled production tools and features; research breakthroughs that portend future commercial products; a ton of experimental videos posted online; widespread press coverage; and AI moving front and center in ongoing negotiations between the studios and the guilds. The idea that AI will have a significant effect on TV and film production in coming years has gone from fringe idea to consensus, very fast.

The idea that AI will have a significant effect on TV and film production in coming years has gone from fringe idea to consensus, very fast.

Even so, when I write that Hollywood may be “disrupted,” what does that actually mean? By disruption, I mean the way Clay Christensen defined it in his theory of disruptive innovation: the process by which new entrants target an overserved market with an inferior, but “good-enough” product, then relentlessly improve the performance of the product and ultimately challenge the incumbents.

While that describes a specific process, it is still imprecise in important ways — namely its extent and speed. Will the disruption be complete or partial? Will it be fast or slow? If you’re an operator or investor, the answers are critically important.

In this essay, I try to be more precise about what I mean by the disruption of content creation and introduce a framework for thinking about how it might play out.

Tl;dr:

To clarify what I mean by the “disruption of Hollywood:” 1) social video is already disrupting Hollywood, but new production tools promise to throw gas on the fire: 2) the initial experiments with AI video are mostly crappy, but that’s how disruption works; 3) this is about tools that make people more productive, not robots making movies; and 4) these tools may benefit Hollywood, but they will likely hurt more than they help.

How fast and to what degree will disruption occur?

Christensen didn’t write much about what factors determine the speed and extent of disruption, but common sense suggests they include: the hurdles for the new entrant to move upmarket; the hurdles to consumer adoption of the new entrant’s product; the degree to which the new entrant changes consumers’ definition of quality; the size and persistence of the high end of the market; and the ease for the incumbent to replicate the new entrant’s business model.

This framework helps explain why newspapers were destroyed by online aggregators, digital native publishers, social, newsletters and vertical marketplaces; major music labels have proven relatively resilient despite the explosion of independent music; and videogame publishers have retained the profitable high end of the market even as most missed mobile gaming, the chief growth engine over the last decade.

Applying the framework also shows why Hollywood is highly vulnerable. While it will likely retain the high end of the market, that market isn’t growing. And consumer adoption of independent content could happen literally overnight.

Hollywood is hardly dead, but it risks retreating into a smaller version of itself.

Revisiting the Disruption of Hollywood

In Forget Peak TV, Here Comes Infinite TV, I first laid out the thesis for why high-quality, professional video content creation — or what I’ll call Hollywood for short — may be disrupted in coming years.

Since I wrote that piece in January, I’ve had a lot of conversations that have highlighted several points I need to refine or emphasize.

1) Professional Video is Already Being Disrupted by Social Video, New Tech Adds Gas to the Fire

There is already effectively an infinite amount of video content (from Infinite TV):

Short form (or “social video” or “user generated content”) is effectively already “infinite.” YouTube has 2.6 billion global users and ~100 million channels that upload 30,000 hours of content every hour. That is equivalent to Netflix’s entire domestic content library — every hour. TikTok has 1.8 billion users. And while we don’t know how many hours of content are on TikTok, 83% of its users also upload content.

And, if we define disruption as the process by which a new entrant enters the low-end of the market, establishes a foothold, gets relentlessly better and then challenges the incumbents, then you could argue that Hollywood is already in the early stages of being disrupted by social video.

YouTube is already challenging Hollywood for the least demanding viewers: kids and unscripted viewers.

As shown in Figure 1, according to Nielsen, YouTube is already the largest source of streaming to TVs. In other words, people watch YouTube on their TV — in their living rooms — more than Netflix, Disney+ or any other Hollywood-content streaming service. And while a lot of this content is music videos, kids playing Minecraft and home improvement videos, YouTube is starting to challenge Hollywood for the least demanding consumers — kids and unscripted viewers.

What’s the most popular kids show in the world? Between its presence on YouTube and Netflix, it’s CoComelon (with over 160 million subscribers on YouTube). The most popular unscripted show? If you were to consider all his videos as a “show,” it’s Mr. Beast, also with over 160 million subscribers, and over 1 billion views per month.

CoComelon is already the most popular kids show and one could argue that Mr. Beast is the most popular unscripted show.

Figure 1. YouTube is Already the #1 Streaming Destination on TVs

Source: Nielsen

Independent/creator content isn’t yet challenging Hollywood for the most demanding forms of content, such as scripted comedies and dramas. When you consider the costs for talent, locations, and VFX and the enormous number of people that need to come together to create a production, those are really hard and expensive to do. My argument is that over time virtual production and AI-assisted tools will lower the entry barriers for this kind of content too, enabling independent/creator content to keep marching up the performance curve. Put differently, these tools will accelerate a disruption process that is already underway. Visually, this process looks a little like Figure 2.

Figure 2. A Visual Representation of Content Disruption

Note: YouTube is meant as a proxy for independent/creator content; TNT is a proxy for cable; ABC is a proxy for broadcast; and Netflix is, well, Netflix. Source: Author

2) At First, AI-Assisted Content Will be Inferior — That’s How Disruption Works

In recent months, there has been a growing amount of video content produced using new AI tools, like RunwayML Gen-2, KaiberAI, Wonder Studio or manipulation of generative imaging tools, like MidJourney, ControlNet or Dall-E to create videos. (Keep in mind that RunwayML Gen-1 and Gen-2, Kaiber and Wonder Studio were all released since January.) I’ve tried to keep a running tally of these new tools and some of the most impressive examples in running Twitter threads, pasted below, but it’s hard to keep up.

A lot of these efforts are just experiments or they are derivative (for some reason, people like to re-imagine famous movies as if directed by Wes Anderson), surreal or even creepy. There are few examples of real narrative-based storytelling. But this isn’t an indictment of the theory. That’s generally how disruption starts — as something that is clearly inferior, but gets better over time.

Disruption always starts as something that appears inferior but gets better over time.

3) It’s About More Productive People, Not Creative Robots

Some of the AI films posted online have been created almost entirely using AI, such as the combination of a script written by ChatGPT-4, text-to-video from RunwayML, a talking avatar by D_ID, voiceover by ElevenLabs, etc. To state the obvious, this is not really “content created entirely by AI” since it takes a human to string all these tools together. Whether content created entirely by AI will ever be more than a novelty is an open question. But the disruptive path I laid out above is not contingent on that. I am merely making the case that these kinds of tools will enable creators to do a lot more with a lot fewer people at a much lower cost, which will alter the competitive dynamic in the market for high-quality video content.

I’m arguing that AI-assisted tools will enable creators to do a lot more with a lot fewer people at a much lower cost, not that content created entirely with AI will take over.

4) These Tools are Available to Hollywood — and to Everyone Else Too

In the online discourse about the effect of these kinds of tools — especially generative AI (GAI) — on Hollywood, many argue that the big studios will co-opt them and therefore be the main beneficiaries.

Arguing that lower cost production tools are good for Hollywood is a little like arguing in 1998 that the Internet was good for magazines.

I think this is unlikely. The good news for Hollywood is that these tools could significantly lower production costs. The bad news is that they will lower the costs for everyone else too and, therefore, the barriers to entry. It’s a little like arguing in 1998 that the Internet is good for magazines because it will lower their distribution costs. In addition, for reasons I recently explained in What Clay Christensen Missed, I think Hollywood will struggle to adopt many of these new tools quickly because of the complex ecosystem of talent, agencies, guilds and trades in which the studios operate. It is telling that one of the key sticking points in the ongoing Writers Guild of America (WGA) strike is the WGA’s demands to limit how the studios can use AI.

That is meant to help clarify what I mean by the “disruption” of Hollywood. Even so, what I have not addressed is really important: to what extent will Hollywood be disrupted, and how fast?

What Determines the Extent and Speed of Disruption?

As mentioned above, sometimes disruption is complete and incumbents ultimately exit the market; sometimes they retain a profitable high end of the market indefinitely. Sometimes it plays out over years, sometimes it takes decades. What determines the difference?

Disruption describes the process by which new entrants target a market and ultimately challenge the incumbents, but it doesn’t predict speed or extent.

As far as I can tell, Christensen never explored the question in depth, but we can apply a little common sense to come up with a simple framework. To do so, it’s helpful to use the vocabulary of another Christensen framework, jobs theory, which he explained in his 2016 book, Competing Against Luck. The premise of jobs theory (or sometimes called Jobs to be Done theory, or JTBD) is that consumers “hire” a product or service to do a “job” in their life. (To quote Harvard Business School Professor Ted Leavitt, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!”) They “fire” that product and “hire” a different one when the benefits of the new product offset the switching costs. It’s important to keep in mind that most products and services do multiple jobs and the importance of each of these jobs differs for different consumers. While there is no consensus definition of the word “quality,” my working definition is that, for each consumer, it is the relative weighting of each of these jobs.¹

Using the language of JTBD, let’s think through the factors that determine the speed and extent of disruption:

Hurdles for the New Entrant to Move Upmarket

In the disruption process, the upstart gets a foothold in the market and then improves its offering. It starts out doing certain jobs, but then gets better at those jobs and keeps adding more jobs and appeals to more customer segments. But how thoroughly and quickly does it improve? Gating factors to moving upmarket may include technological complexity, regulation or incumbents’ control of a scarce resource.

Consider one of the canonical examples of disruption that Christensen highlighted in The Innovator’s Dilemma — minimills’ disruption of integrated steel mills. Owing largely to the technological complexity, required capital investment and regulatory requirements of higher grade steel, the process took decades. Minimills entered the market with the least demanding and lowest cost form of steel, rebar, in the 1960’s and ‘70’s. In the late ’80s, they developed flat-rolled steel and it took another 15 years to move into the highest quality sheet steel. And that disruption is not complete. As of 2017, integrated steel mills still produced about 30% of steel in the U.S.

Hurdles for Consumer Adoption

The prior point focused on the hurdles for new entrants to move upmarket, but another factor is the hurdles for consumers to adopt new entrants’ products. These hurdles include the risk aversion of the customer (for instance, individuals and small businesses may adopt some technologies faster than large enterprises and governments owing to lower risk aversion) and switching costs. Switching costs include the consumers’ sunk investments in the incumbents’ products or services, the learning curve on the new product, entrenched business relationships and the hardware replacement cycle. Consider the obliteration of standalone driving navigation devices (Garmin, TomTom) by mobile driving apps, like Waze or Google Maps. The hurdles to consumer adoption were negligible because almost all drivers have smartphones anyway.

Degree to Which the New Entrant Changes the Consumer Definition of Quality

As I’ve discussed in other essays (see Four Horsemen of the TV Apocalypse), one of the more insidious, but less discussed, elements of the disruption process is the tendency of new entrants to introduce new features that change the consumer definition of quality.

AirBNB is a favorite example. It started with a low-end offering, targeting people who needed a room but couldn’t afford a hotel. However, it also introduced new features that most hotels simply can’t offer, like quaint neighborhoods, more privacy, full working kitchens, a backyard barbeque and substantially more space. For some customers, these new features have completely changed their definition of quality and they no longer consider hotels when traveling.

Size and Persistence of the High End of the Market

Sometimes, the new entrant never moves all the way upmarket. For instance, maybe it makes business model choices that foreclose the high end or it can’t overcome technological or regulatory hurdles. Or perhaps the market of non-consumers is large enough that it doesn’t need to directly target the incumbents’ highest-end customers. In these cases, there are two critical questions for incumbents: how big and how persistent is the residual high-end market? Why the size of the market is important is obvious. The persistence of the market depends on how broadly the new entrant changes the consumer definition of quality. If the consumer definition of quality changes materially even for high-end consumers, then the traditional high end of the market may disappear.

Take AirBNB again. Even though it has changed the definition of quality for many consumers, it still can’t (and likely won’t ever) compete on certain “jobs” that are important to many business travelers, like convenience, 24-hour service, security, common spaces to meet business contacts and proximity to business districts. And business lodging is a massive market. Similarly, Coursera will probably never compete for many of the jobs that are highly valued by college students and their parents, like a gradual transition into adulthood, social life and a valued alumni network. On the other end of the spectrum, consider film photography. The advent of digital photography so completely changed the definition of quality that the high-end market for film — professional photographers — eventually all but disappeared.

Ease for Incumbent to Replicate the New Entrant’s Business Model

In theory, incumbents can head off disruption by rapidly matching the pricing and product offerings of the new entrant. In practice, a company’s ability to do this is heavily influenced by the complexity of the ecosystem in which it operates, as I explained in What Clay Christensen Missed:

Often, firms get disrupted not because they don’t understand the disruption process, see it coming or know what’s at stake. They don’t even get disrupted because of the difficulty of changing internal processes. They get disrupted because companies operate in complex ecosystems of stakeholders with misaligned interests: employees (including well-paid, powerful executives), unions, vendors, distributors, “complementors,” board members, shareholders, etc.

In the best cases, this is really hard, in others, it is essentially impossible.

Models of Media Disruption: News, Music and Gaming

Before using this framework to predict the possible speed and extent of disruption of Hollywood, let’s see if it can help explain the recent history of other similar media businesses, namely newspapers, music labels and videogame publishers.

I call these businesses similar because, like TV and film studios, they are all intermediaries between creators and consumers (whether those creators are salaried employees, like journalists and videogame developers, or independent contractors). All historically earned a critical place in the value chain by performing functions that creators couldn’t easily do themselves, such as financing production, handling monetization (ad sales, licensing, wholesale sales, retail sales), developing distribution networks or brokering distribution deals and marketing. (I.e., they are all “producer/publishers” in the simplified generic media supply chain in Figure 3.)

Figure 3. A Simplified Media Value Chain²

Source: Author.

All three have been disrupted to some degree as technology has reduced the cost or complexity of most of these activities, making it easier for both independent studios/publishers/labels and individual creators to disintermediate their roles. But the extent of this disruption has been quite different. Let’s explore why.

Newspapers, music labels and videogame publishers are all similar to TV and film studios: they are intermediaries between creators and consumers. They have all established a critical role in the value chain by doing things that are very hard or expensive for creators to do themselves, but technology is making all those things easier.

Newspapers: Near-Complete Disruption

Historically, newspapers did several jobs. They aggregated national newsgathering services (AP and Reuters); produced regional/local news and opinion; and acted as a local marketplace for employment, real estate, used cars and other used goods (the classifieds). The Internet disrupted all three. It made it possible for online news aggregators to provide the same aggregation services; new digital native publishers to emerge; journalists and independent creators (both amateurs and professionals) to disintermediate newspapers and publish directly to digital native publications, blogs, newsletters and social networks; and it enabled the creation of multi-sided vertical online markets (Craigslist, AutoTrader, Ebay, Indeed, Zillow, etc.) that supplanted the classifieds.

The newspaper business has been eviscerated over the past two decades. Figure 4 shows aggregate newspaper revenue in the U.S. (both advertising and circulation) graphed against total U.S. online advertising. This is an admittedly blunt and imperfect comparison (the online advertising numbers include categories that are not strictly competing for newspaper ad dollars, such as online video advertising), but it roughly shows the point: aggregate newspaper revenue is down by 2/3 over the last two decades, from close to $60 billion to around $20 billion today. All of that revenue has been vacuumed up by online advertising, primarily Meta and Google, and online marketplaces.

Figure 4. Newspaper Revenue is Down 2/3 Since 2000

Sources: Pew Research Center, IAB, PwC.

Running the newspaper business through our framework shows why. (Since we’re looking at these dynamics from the perspective of the incumbents, factors with an❌ favor the new entrant, those with a✅ favor the incumbent and those with a ❔are neutral or unclear.):

❌ Ease for new entrants to move upmarket: For both independent (i.e., non-newspaper) written information/opinion and vertical marketplaces there were no major barriers to move upmarket. The high end of the market for information is brand-name journalists, but “newsletter in a box” services like Substack and Beehiv have made it easy for journalists to cut newspapers out and go direct-to-consumer. Online marketplaces had to establish a sufficient network of buyers and sellers to overtake classified services, but that didn’t take long. Put differently, at this point there are few, if any, jobs that newspapers do that aren’t done by online providers and, in many cases, better.

❌ Hurdles to consumer adoption: The chief hurdles to adoption were widespread broadband access, widespread mobile device adoption and shifts in consumer behavior toward accessing information online. The only gating factor to all three was time, but that has since passed.

❌ Degree of change in consumer definition of quality: Online news changed the consumer definition of quality in important ways: consumers now expect information to be immediate and it raised the bar for what people are willing to pay for. Many people also now rely on their chosen panel of friends or experts on social networks, like Facebook and Twitter, to act as their news filter, not the editorial staff of a newspaper. In the classifieds business, vertical online marketplaces have offered many new features, such as easy search, customized alerts, rich media (more photos and videos), the ability to communicate or transact with counterparties seamlessly online, larger selection, shipping, buyer protection and escrow services, etc., that have completely changed the definition of quality.

❌ Size and persistence of high-end market: Because of the ease for new entrants to compete at the highest end of the markets — analysis and opinion from brand-name journalists and sales of high-end real estate, cars, etc.— and because of the broad shift in the consumer definition of quality, there is no residual high-end market left to newspapers. There are a few highly trusted brands, such as The New York Times or The Financial Times, which can fulfill the job of “provide me information I can trust” for some consumers better than online outlets, newsletters, aggregators or social platforms, but this is more the exception than the rule. For some consumers, “deliver me a physical newspapers daily” is still an important job, but this is a small and probably declining market. In the classifieds business, vertical online marketplaces have so altered the definition of quality that newspaper classifieds sections have shrunk dramatically or been curtailed in many markets.

❌ Ease for incumbent to replicate new entrant’s business model: Whether it would’ve been easy for newspapers to launch their own news aggregators, online marketplaces or social networks is moot — some tried, but it didn’t help much.

Major Music Labels: Relative Resiliency

The recent history of the major music labels is very different, as I discussed in Will Radio Save the Video Star?.

Newspapers were obliterated, while major music labels have proved resilient. Why?

Historically, the primary role of music labels was artist development, financing, marketing and distribution. The barriers for independent labels and artists to disintermediate the labels have fallen substantially over the last 15–20 years. Owing to sophisticated in home production software (DAWs, like LogicPro) and hardware; streaming services (Spotify, Soundcloud, etc.); and social networking, today artists can self-produce, self-distribute and market through their own social followings.

Owing to these lower barriers to entry, there has been an explosion of independent music in recent years. Spotify boasts 11 million artists (as of 4Q21) and 100 million tracks. Spotify estimates that only 200,000 of the 11 million artists on the platform are “professional” musicians, implying the other 98+% are not represented by any label, major or independent. An estimated 100,000 new songs are uploaded to streaming services each day. I estimate that half of the new tracks on Spotify were added in the last three years and that less than 10% of the tracks on the service are repped by major labels.

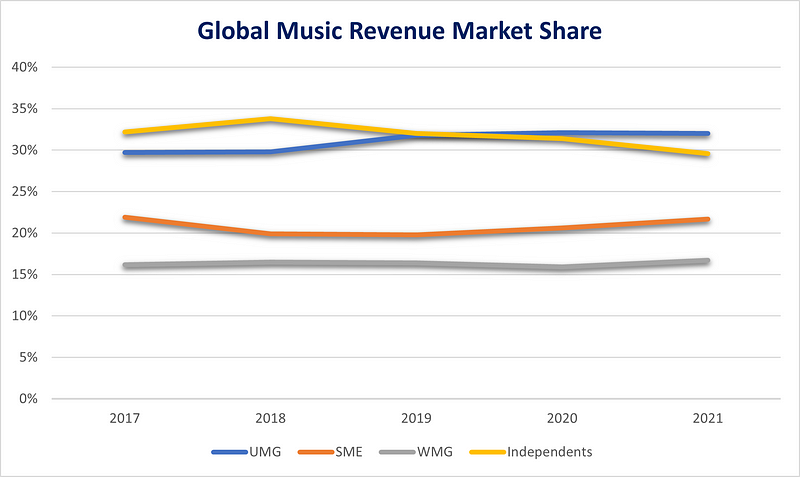

Nevertheless, the major labels have proven surprisingly resilient. As shown in Figure 5, the three major music labels (Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment and Warner Music Group) have actually gained revenue share over independents over the last few years. As shown in Figure 6, while they have lost share of Spotify streams, the majors and Merlin (a consortium of large independent labels) still represent about 75% of all streams and the pace of decline has flattened in recent years, even as the quantity of music from independent creators has exploded.

Figure 5. The Majors Are Dominant and Have Been Gaining Revenue Share

Source: Omdia (Music & Copyright).

Figure 6. The Majors and Merlin Still Have ~75% Share of Spotify Streams, Even with 100,000 New Tracks Uploaded Daily

Source: Spotify Form 20-F.

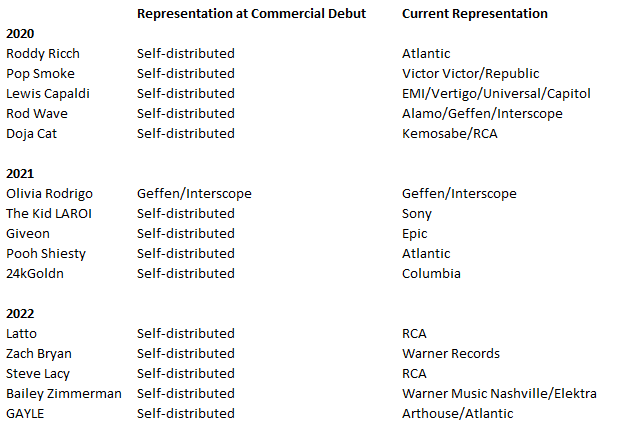

In addition, while it is possible for artists to circumvent labels and go direct, few successful musicians do. Figure 7 shows a list of the Billboard top new artists for the last few years. Almost all of them (other than Olivia Rodrigo, who was already a Disney Channel star) started out by self-distributing, but all now have major label representation.

Figure 7. All of the Billboard Top New Artists of the Last Few Years Have Major Label Deals

Source: Billboard, Author analysis.

Let’s explore music labels through the framework:

✅ Ease for new entrants to move upmarket: In music, for new entrants to move upmarket would mean higher quality/more popular³ acts going to independent labels or direct. As I discussed in Will Radio Save the Video Star?, while there are no technical hurdles, there are significant business hurdles. Most important, major labels have the scale and resources to help artists navigate the complexity of the music business, which has multiple revenue streams and is global. They also have a leg up in artist development, because they can attract the biggest-name producers and musical collaborators. And they retain substantial bargaining power over streaming services, largely due to the importance of catalog music, which the majors control. As a result, even the most powerful artists, who are best positioned to go direct, still have major label deals (even if they also have tremendous bargaining power over the labels).

❌ Hurdles to consumer adoption: There are no hurdles to consumers listening to independent music. It sits side-by-side with major label music on streaming services; as mentioned, the vast majority of music on streaming services is non-major label — probably >90%.

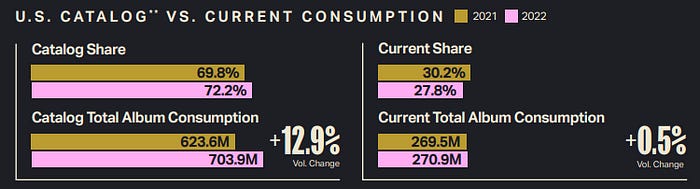

✅ Degree of change in consumer definition of quality: The consumer definition of quality in music has arguably changed very little in the last few decades. Perhaps most relevant is that catalog is still extremely important. As shown in Figure 8, according to Luminate, last year 72% of music consumption was catalog (which is defined as music that has been on the market for 18 months or longer and has fallen below 100 on the Billboard Top 200 chart). While popular culture focuses on the newest music, most of what people actually listen to is catalog, which is largely controlled by the major labels.

Figure 8. An Estimated 72% of U.S. Music Consumption is Catalog

Note: ** Catalog = 18 months or older and have fallen below №100 on the Billboard 200 Chart and don’t have a single that is current on any of Billboard’s radio airplay charts. Source: Luminate.

✅ Size and persistence of high-end market: If the high end of the market is defined as the current and catalog recordings of the most popular artists, then it is still the bulk of the market.

✅ Ease for incumbent to replicate the new entrant’s business model: As noted above, most independent artists who break out sign major label deals. It is also relatively easy for the major labels to buy independent labels and distribution services and thereby subsume the forces of disruption. For instance, Sony purchased The Orchard and AWAL, two independent distributors, in recent years.

Videogame Publishers: A Middle Ground

Gaming has also arguably been disrupted over the last decade by mobile gaming. Console and mobile have very different business models. Mobile games also tend to be casual, with less demanding gameplay and shorter session length, and a more diverse user base.

AAA console titles have development costs that rival blockbuster movies— CD Projekt Red, developer of Cyperpunk 2077, disclosed it spent more than $300 million on development — require heavy marketing spend and entail significant manufacturing and platform fees to the console manufacturers. While many console titles have added downloadable content (DLCs), like expansion packs, skins, etc., and subscription services, the primary model is still selling titles at about $60 each. By contrast, owing in part to game development platforms like Unity and Epic’s Unreal Engine and different consumer expectations, the development costs for a mobile game may cost ~$10,000-$100,000, or 3–4 orders of magnitude less. The vast majority of mobile games are also free-to-play and make their money from in-app purchases, so the economics are largely dependent on the size of the funnel and LTV/CAC (which is a function of both marketing efficiency and conversion rates to paying players).

With much lower barriers to entry, there are many more mobile games — the major console platforms each support several thousand games and there are over 50,000 PC games available on Steam, but there are hundreds of thousands of mobile games on both the iOS App Store and Google Play. Similar to news and music, the vast majority of these games are produced by small teams who circumvent the biggest console publishers (Microsoft, Sony, Electronic Arts, Nintendo, Activision, Take-Two, etc.).

As shown in Figure 9, the incumbent console publishers were largely unable to adapt to the mobile business model. While the two largest game publishers in 2012, Activision and EA, were among the top 10 mobile publishers in 2021, they didn’t retain their console share. The good news for the incumbents is that mobile gaming attracted a lot of “non-customers” and the console and PC business has continued to grow at a relatively rapid clip — especially when compared to anything that is considered “media” (Figure 10). The bad news, also shown in Figure 10, is that mobile is now half the business.

Figure 9. The Biggest Console Publishers in 2012 Didn’t Keep Pace in Mobile

Notes: Supercell is majority owned by Tencent. Zynga was acquired by Take-Two in May 2022. Sources: Ubisoft via gamesindustry.biz, Appmagic.

Figure 10. Mobile is Now Half the Business

Source: Morgan Stanley.

So, the disruption of gaming stakes out a kind of middle ground between the massive value destruction of newspapers and the relative resiliency of the major music labels. Why?

✅ Ease for new entrants to move upmarket: So far, it’s proven very difficult for mobile developers to target the high end of the market, which is hardcore gamers and, for the most part, they don’t try. Unlike consoles, which have uniform technical specifications (i.e., every PS5 is the same), mobile developers needs to cater to a wide range of devices. Generally, mobile devices don’t have the processing power, screen size and control capabilities of consoles. There are a few exceptions, like Fortnite, PUBG and Genshin Impact, that have successfully translated to mobile. But this is more the exception than the rule.

❌ Hurdles to consumer adoption: Like any other mobile app, there are no barriers to consumer adoption.

✅ Degree of change in consumer definition of quality: Mobile gaming has introduced new “jobs” to gaming and consequently mobile games tend to have a different set of use cases and definition of quality than console or PC games. They usually have a much quicker learning curve, they can be played in short sessions with a faster payoff and they are easier to play while multitasking. For most console and PC games, by contrast, the markers of quality tend to include higher-fidelity graphics, much more complex gameplay and storylines, live social features (e.g., chat) and more immersive, longer sessions.

✅ Size and persistence of high-end market: As noted in Figure 10 above, the high end of the market, console and PC games, has continued to grow at a healthy pace despite the emergence of mobile.

❔Ease for incumbent to replicate the new entrant’s business model: Large publishers have successfully bought their way into mobile, but have struggled to build mobile operations organically. The most successful acquisitions of a mobile games developer are arguably Tencent’s purchase of a majority stake in Supercell (Clash of Clans), Microsoft’s purchase of Mojang (Minecraft) and Activision’s acquisition of King (Candy Crush). Nevertheless, as noted, none of the major AAA publishers have maintained their console share in mobile.

Figure 11. Hollywood is Vulnerable

Note: Factors with an❌ favor the new entrant, those with a✅ favor the incumbent and those with a ❔are neutral or unclear. Source: Author.

Applying the Framework for TV and Film Studios

The last and final step is to apply this framework to TV and film studios to address the critical question posed before: to what extent and how fast might Hollywood be disrupted?

✅ Ease for new entrants to move upmarket: The highest end of the market for TV and film is big-budget, high production value projects with big name directors/showrunners and actors and well-known IP. Will Steven Spielberg or Martin Scorsese lean into these new AI-enhanced production tools and create Hollywood-quality productions and disintermediate the studios and distribute them on YouTube? Probably not. In addition, the studios still control the most widely-recognized franchises, like Star Wars, Marvel, DC, Harry Potter, etc. Could high-production value hits emerge from the tail of independent content? For sure. But it will likely be very difficult for independent creators to approach the highest end of the market for Hollywood content anytime soon.

❌ Hurdles to consumer adoption: Much like the examples above, there are no real barriers to consumer adoption of independent content. The disruption of video content distribution by Netflix took a long time because it required wide broadband adoption, smartphone and connected TV adoption and a change in consumer behavior to embrace streaming. By contrast, the adoption of independent content could happen literally overnight. As shown above in Figure 1, YouTube is already the #1 source of streaming to TVs. If there was a compelling independently-produced scripted TV show distributed on YouTube today, it could be the most popular show in the U.S. tomorrow.

❔Degree of change in consumer definition of quality: As I discussed in Infinite TV, it seems clear that social video is changing the consumer definition of quality for some consumers:

Most studio executives equate TV and movie quality with very high-cost attributes: high production values; established, well-known IP; brand name directors, show-runners, actors and screenwriters; and expensive effects, often signaled by equally expensive marketing campaigns. Short form doesn’t (currently) compete on these attributes. But it ranks much higher on other attributes, like virality, surprise, digestibility, relevance to my community and personalization. These attributes are not inherently expensive.

To the extent that consumers consciously substitute short form for traditional TV, this reveals that their definition of quality is shifting toward de-emphasizing high-cost attributes, and, in the process, lowering the barrier to entry. It seems like this is what’s starting to happen. According to TikTok, as of March 2021, 35% of users were consciously — and therefore intentionally — watching less TV since they started using TikTok.

However, it is hard to predict how broadly the consumer definition of quality will change. Intuitively, it is a generational shift; older consumers will still likely define quality as they always have, namely high production values, while younger consumers will more highly value performance attributes like virality, authenticity and rapid consumption. But will there still be an appetite for blockbuster franchises even among young viewers? Probably.

❌ Size and persistence of high-end market: Even though the high end of the market for TV and film may persist, a core challenge for Hollywood is that it isn’t growing. I won’t relitigate the point here, but as I explained in Video’s Fundamental Problem: It Over-Monetizes, the chief reasons are that video consumption is already too high (the average adult watches more than 5 hours of video per day) and, owing to the cozy cartel between the cable networks and cable distributors, historically people paid too much for video they weren’t consuming.

❌ Ease for incumbent to replicate the new entrant’s business model: As I’ve written before, I think it will be very hard for Hollywood studios to adopt these new production technologies because of the complex ecosystem of talent, unions, agencies, etc. in which they operate.

The Death of Hollywood Has Been Greatly Exaggerated, But it is Highly Vulnerable

In recent months, I’ve seen a few tweets that Hollywood is “over” or “dead.” Or sometimes “RIP Hollywood.” A good tweet requires a compelling hook, so I understand why people use these kinds of phrases. But, to be clear, when I write that content creation is on a path to be disrupted over the coming years, by no means am I predicting that Hollywood is “dead.”

The very highest end of the market, with A-level talent and the most widely-loved franchises, is safe for the foreseeable future. But the industry is vulnerable. As described above, the conditions are ripe for very rapid consumer adoption of independent content. It is also an open question how big this high-end market is and how it is can grow.

The risk for Hollywood: over time, it retreats into a smaller version of itself.

Among the comparisons above, I think Hollywood is most analogous to gaming, with one crucial difference. Like the AAA publishers, Hollywood will probably continue to control the high end of the market indefinitely. The key difference is that the console and PC gaming markets are still growing, while the core market for high-end video is not. In gaming, there was a big market of non-consumers to target. There isn’t in video. The risk for Hollywood is that over time it is relegated to big budget productions of a few key franchises — a stagnant or shrinking market — and retreats into a smaller version of itself. This is not the most dire outcome, but adjusting to the reality that Hollywood is no longer a growth business, or in decline, would be a wrenching process.

¹ For instance, why did you “hire” your car? For transportation, of course. But you might have hired it to “provide me a comfortable commute,” “get me through tough weather,” “go off-roading,” or “carpool my kid and her friends to soccer.” Explicitly or not, you probably also hired your car to “send a message about my identity,” including what you wish to convey about your socioeconomic status, environmental consciousness and perhaps even marital status or political leanings. Christensen often made the point that customers should be segmented by the jobs they are trying to get done, not by demographics or geography.

² Often, the producer/publisher has an affiliated aggregator/distributor arm (such as media conglomerates that include TV and film studios, broadcast and cable networks, TV stations, streaming services and even cable systems) and sometimes the producer/publisher just brokers distribution (like music labels).

³ Above, I defined “quality” as consumers’ relative weighting of the “jobs” that a product or service does. By this definition, for goods or services of equal price, popularity is equivalent to the average definition of quality.