Over the last year, I’ve given this talk, or a variation of it, a couple of dozen times, so I decided to post it to a broader audience. It’s an attempt to condense my recent writing into a 30-minute presentation.

Here’s a video of the presentation and here are the slides. In it, I discuss:

Why four themes in media—fragmentation, disintermediation, concentration (of power and attention) and virtualization—represent the “low background hum” of operating in the media business today.

How these themes will affect the distribution of value between creators, traditional intermediaries, new intermediaries and consumers.

The two disruptions of TV: the disruption of content distribution over the last decade and the disruption of content creation over the next.

Why all the current problems in Hollywood are a lagging indicator of the last disruption.

Why the biggest threat for creatives is not studios replacing them with GenAI, but GenAI vastly increasing the supply of competitive content and undermining the economic foundation of the studios’ businesses.

Why GenAI is not just a way to make movies more cheaply, but could change the bases of competition in video.

Why this disruption could happen even faster than the last one.

What becomes scarce as content approaches infinite and the opportunities that may present.

Alternatively, below is the transcript (lightly edited for clarity) and corresponding slides:

Transcript

There is a lot of noise in the media business day-to-day and, especially when you’re in the thick of it, it can be hard to know what’s important and what’s not. A key premise underlying my writing is that there are important structural changes underway in media and, if you can make sense of them, not only can you predict where the business is heading longer term, but you can also pick out the signal from the daily noise.

So, what I want to do over the next 30 minutes or so is take a step back talk about those structural changes, and I'm going to make the case that the media business is going to change more radically in the next five to 10 years than it has in the last decade.

As I said, I've given this talk (or a variation) a bunch of times and here are a few of the places I’ve spoken.

I'm going to try to tee up and answer three questions.

How will value be redistributed in media over the next five to 10 years?

To drill a little bit further into the TV business. It's been disrupted. So what happens now?

A lot of this is going to be pretty bearish for the traditional media industry. So, I think a good place to end is what opportunities emerge out of all this.

I discuss all these topics in more depth in my Substack, The Mediator. Here, I’m trying to distill what is tens of thousands of words into 30 minutes. If you want to go deeper into any of these topics, I encourage you to check it out and sign up. It’s free.

Tectonic Trends in Media

Let's start with the tectonic trends in media.

To set the stage, it's important to understand that on an inflation adjusted basis, media is not growing. That's the orange line there. And this is all media. This is video, print, social, gaming, everything.

Why is that? Fundamentally, the media business, of course, is about monetizing attention and engagement.

But the problem is that there really is not a lot more attention to go around.

What you can see here on this top chart is that the average U.S. adult spends 13 hours a day with media. That's 60% of waking time. And although this is a different source, the bottom chart shows a time series of time spent. What you can see here is that it grew with the advent of mobile. Then we got a nice bump—I guess not much about COVID was nice—but we got a bump with COVID, and then it really has been stagnant since.

If total time spent is not growing, it's also very hard for value to grow and that's why this is the most important question: how value will be redistributed along the ecosystem among these kids all sitting around, fighting for their piece of the pie.

To answer this question, earlier this year, I wrote a series of four posts (here are 1, 2, 3 and 4) about what I'm calling the tectonic themes in media. By tectonic, I mean that they are mostly unnoticeable day to day, but very powerful, and I think inevitable.

They are:

The fragmentation of attention.

The waning power of intermediaries.

The tendency of networks to concentrate both power and attention.

What I call virtualization, which is this idea that the increasing blurring of the lines between the digital and the physical will potentially open up new ways to use media.

But I think collectively, these four themes represent the low background hum of operating in the media business today. So, let me talk about each of these.

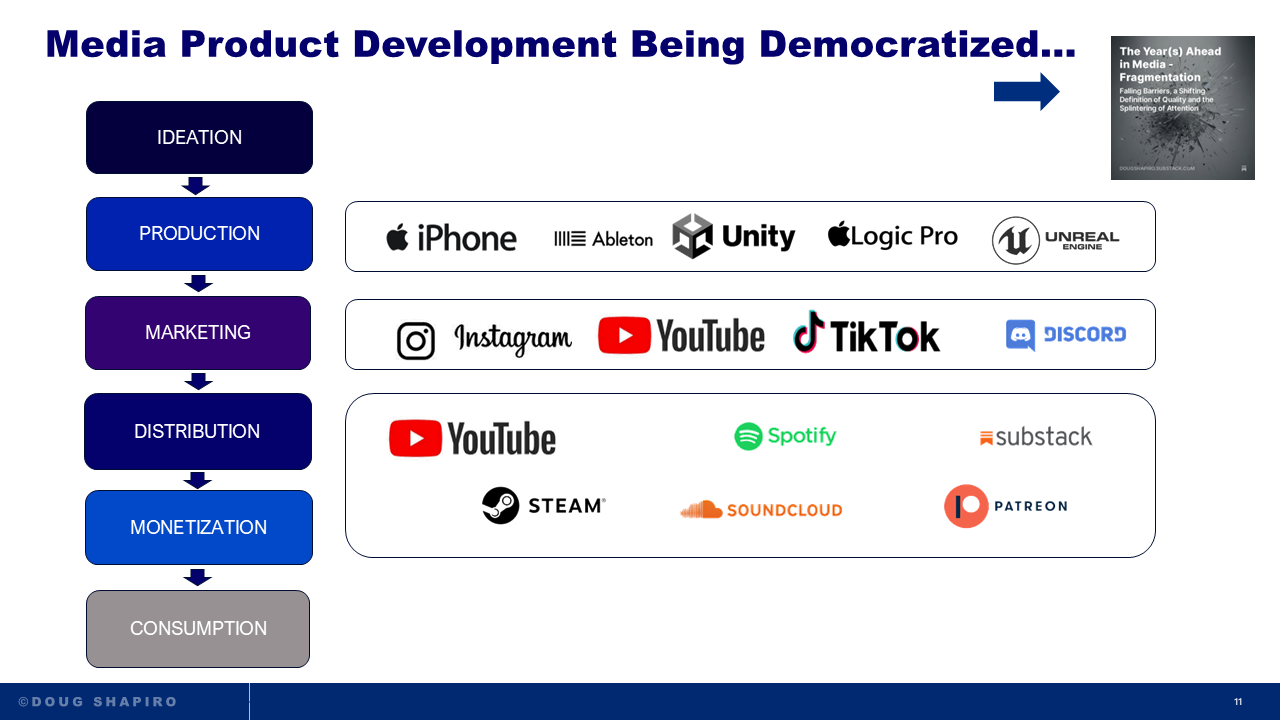

The first is fragmentation. Everybody knows that attention is fragmenting, but let's talk about why. It's happening for two reasons. The first is that barriers to entry are falling along the entire media product development process: production, marketing, distribution, monetization. To varying degrees, all are being democratized by technology.

As a result, there has just been an explosion of stuff, as we all experience directly every day. But let's put some numbers on it.

In TV and film, I estimate that Hollywood, generously, produces about 15,000 hours a year of TV and film, but there's 300 million hours a year uploaded to YouTube.

In music, there are 200,000 professional and “professional aspiring” musicians on Spotify, as Spotify defines it, but there's 11 million total artists on Spotify. So, that means that less than 2% of all the artists are considered professional or “professional aspiring.”

And, in games, you have 3,000 games on a platform like Xbox, but you have 100,000 games on Steam, and it's on track for 17,000 new games this year.

And these numbers are all only going to get more dramatic as GenAI evolves.

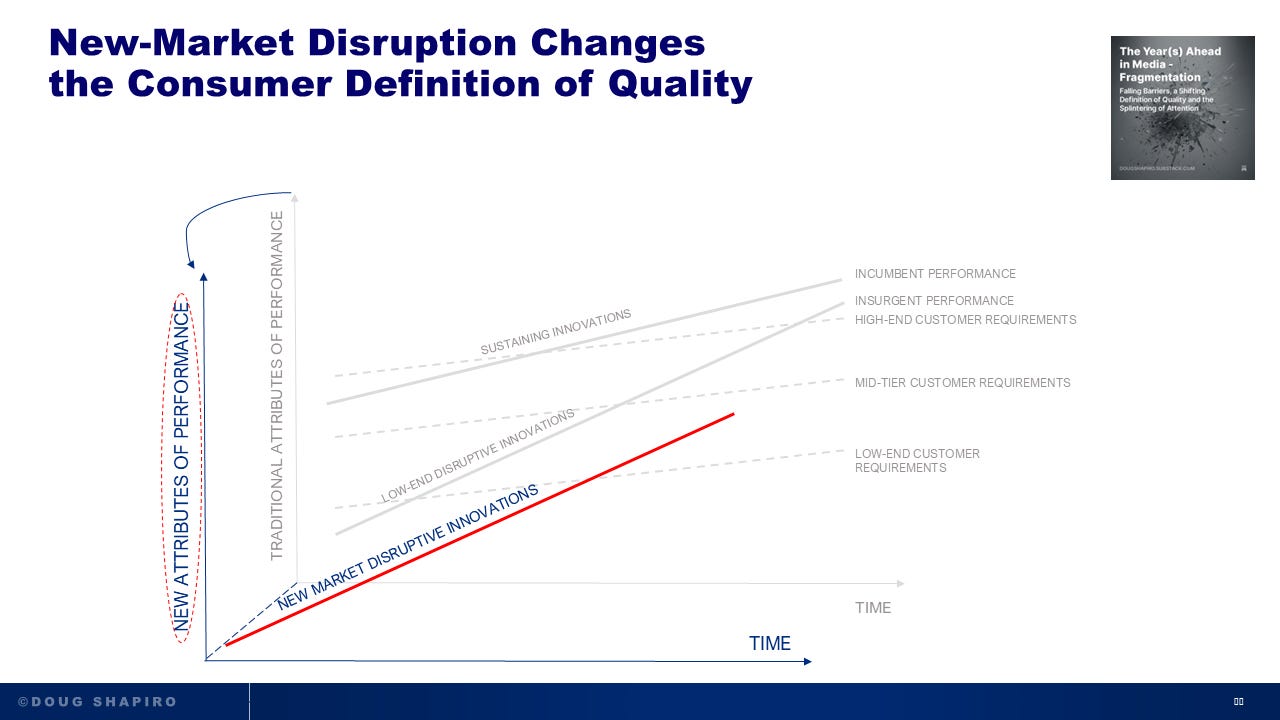

This explosion of content is what Clay Christensen would have called a low-end disruption. New entrants come in with a low quality product—as measured against the traditional definition of quality—the incumbents ignore it, but it keeps getting better and eventually it challenges the incumbents. And, to be clear, a lot of the stuff is very low quality. A lot of it, if not the vast majority, is not stuff you'd want to watch or listen to. It is what you could call crap. And most of the stuff that's going to be created with GenAI will also be crap.

But this takes us to the second reason that fragmentation is happening. I think it's a little bit less well understood than the first. Another facet of disruption is that new entrants don't only compete on the traditional measures of performance, they introduce new attributes. If those attributes or features take hold with consumers, then they change the consumer definition of quality.

The example I always think about here is Airbnb, which, when it came out, I thought it was just about the worst idea I ever heard, paying to stay on someone's couch. But as it has evolved, it has introduced all kinds of new features to lodging, things like having a full working kitchen or a driveway, being in a quaint neighborhood, having more closet space or whatever. In the process, it has changed the consumer definition of quality in lodging for a lot of consumers.

The same thing is happening in media, right? When you find a underground artist on SoundCloud or an indie game on Steam, or some creator that you find very relatable or authentic on YouTube, that's a fundamentally different experience than consuming professionally-produced content.

You can see this evidence of fragmentation occurring across media.

In video, I estimate that about 1/4 of all time spent with video today is social video, YouTube, TikTok and Reels, mostly.

In music, the majors have been really resilient, but their share of streams on Spotify falls every year. It was close to 90% in 2017, now we are closing in on 70%.

And in gaming, the same thing is happening. A decade ago, casual, mobile, hyper casual, really barely existed and today, it's half of the business.

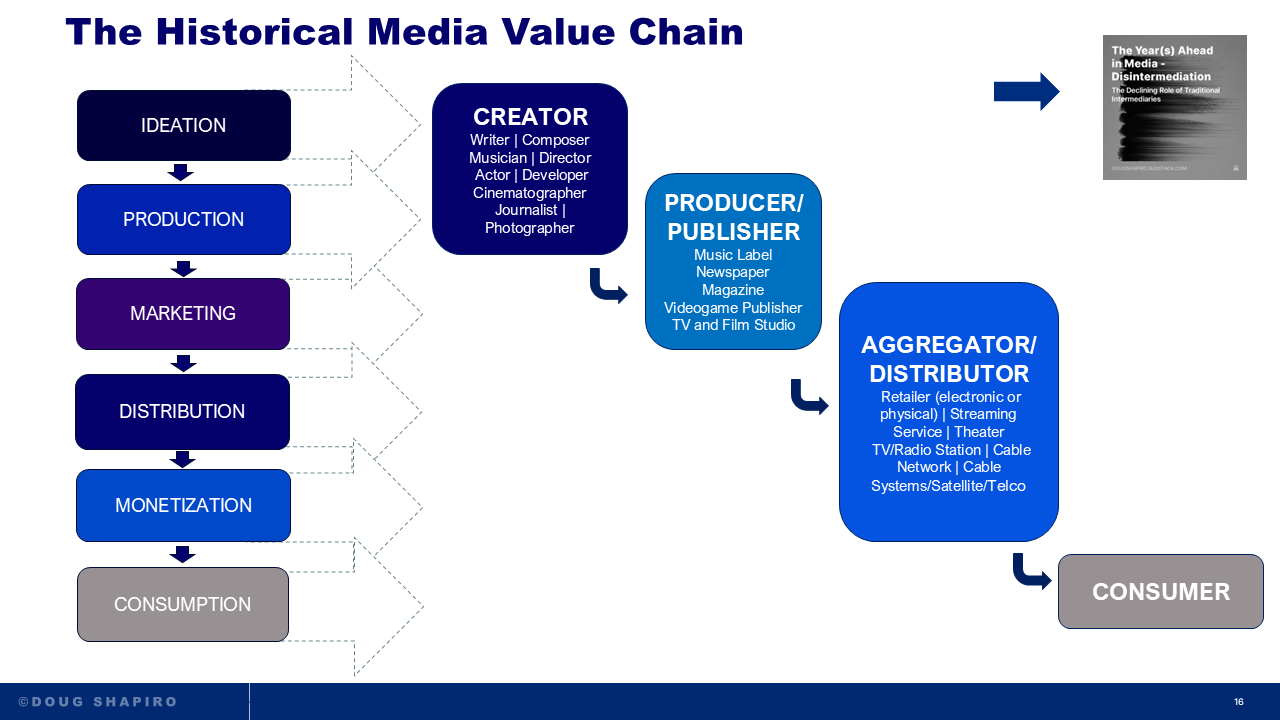

The second theme, which is directly related to the first, is the idea that the role of traditional intermediaries is diminishing. What this chart shows is the historical value chain in media, which goes from creators to publishers to distributors to consumers.

Here's another way to look at it, namely that the household names in media historically have really been intermediaries between creators and consumers. And they have extracted most of the value in the media ecosystem because they have done things that are really hard for creators to do themselves. They finance production, they assemble talent, they do the marketing, monetization, distribution.

But as I mentioned, technology is systematically making it easier for creators to do those things themselves. And if you look at this chart of the emerging media value chain and compare it to the prior one, you can see creators are moving down the stack.

What that means in practice is that they have either more bargaining power over the intermediaries, or in some cases, they can circumvent them altogether. So, you take an example like Taylor Swift, producing and distributing the Eras Tour movie by herself. Or, recently, Ryan Coogler negotiated with Warner Bros. to get back the master to his movie in 25 years. That's pretty common in music, but it is almost without precedent in the movie business.

The third theme is about what happens when so much consumption moves to networks. Historically, most media distribution was one-way. It was delivered to consumers and there wasn't much of a feedback mechanism. But of course, today, most consumption happens on two-way networks. And the most important thing about networks is that they're subject to these really powerful positive feedback loops that make the strong, stronger. There's both a supply-side and a demand-side dynamic here.

On the supply side, this results in these really powerful network effects which have created massively powerful platforms. We all know this, but the point on this chart (on the left) is that the market cap of the smallest platform, META, is bigger than the entire media industry combined. Then this chart (on the right) is showing you global ad revenues. It's a little dated, because it’s for 2022, but the red bars are, again, media companies. The point here is that the biggest companies in media today are no longer media companies.

On the demand side, what's happening is that networks tend to amplify popularity. The popular becomes more popular, and that's partially because consumers use popularity as a signal of quality, and there's also an element of social currency involved in consuming popular stuff. In any case, without going too deeply into it (see Power Laws in Culture for an in depth analysis), the point is that you end up with these really big hits. You end up with these big cultural touchstones, again, Taylor Swift or Barbenheimer or GTA 6, if and when it comes out. So even though the tail is getting longer because of fragmentation, the head is getting ever higher, and you end up with these really big hits and these power law or power law-like distributions.

This slide shows an analysis I did for box office in the U.S., demand for Netflix shows, Patreon patrons and streams on Spotify. What it shows is that in all cases, these distributions are very extreme, and in some cases, becoming even more extreme.

There are a couple of of negative implications for traditional media companies.

One is that the middle is going away. The middle is getting hollowed out and it's historically been a very lucrative part of the business. Another problem is that the business is getting riskier because the distribution of returns is becoming more extreme. And the third problem is that the artists—the creators or creatives—at the very tippy top, of course they know they're at the tippy top, and so they use that knowledge to extract more leverage than ever, as I was just discussing.

The fourth theme is the most hopeful for the media industry, but also the vaguest and furthest out. The idea is that there are going to be new media modalities, enabled by technology. In the essay, I talk about three categories of new modalities: more immersive experiences, more engaging experiences and those that create more time. The Apple Vision Pro has been a bit of a disappointment, but in theory, maybe eventually VR opens up a new software upgrade cycle for movies? Or could autonomous vehicles free up 40 or 50 minutes of commuting time for other uses? The problem here, of course, is that all of these things are unclear, pretty far out, and really hard to underwrite today.

To sum this up, the idea is that more attention will perennially shift into the tail, especially with the advent of GenAI; the bargaining power of traditional intermediaries is declining; you have this rising concentration of power in a handful of platforms and attention in a handful of hits; and you have this very vague hope of a brighter future.

This chart tries to answer the question that I posed at the very beginning, how value will be redistributed along the ecosystem. Without reading it, the bottom line is these themes are good for the very top creators. It's really uniformly not good for the traditional intermediaries. They’re good for the platforms, although the question here is whether the size of the prize is big enough to move the needle for them. And they’re good for consumers in the form of more choice and lower costs.

Another way to look at it is this. Traditional media is getting squeezed on the one side by platforms that don't really need to make money in media. A lot of them are using media to cross-subsidize some other part of their business. On the other side, there's this infinite army of creators.

The Two Disruptions of TV

Now, I want to move to the second question I raised and talk about TV in the U.S. TV is going through those same kinds of dynamics I mentioned, but I want to talk a bit more about the ideas of fragmentation and disruption.

The one sentence summary here is that the last decade in TV and film was defined by the disruption of content distribution, and I think the next decade will be defined by the disruption of content creation.

Let's walk through a quick history lesson. This is the video value chain, which is a more specific version of the generic media value chain that I showed earlier.

The value in any value chain is a function of the moats in the value chain, or the barriers to entry. That is a very basic economic concept, namely that if you have a business with no barriers to entry, then new entrants will come in and compete away profits. So, the moats are very important. And historically, there were two big moats in TV and film, one around distribution, because it is very capital intensive and expensive, and the other one around content creation—or what's called here production—because it is also very risky and expensive.

Because of those moats, the TV business was a great business, one of the greatest businesses ever, but it was also ripe for disruption, if those moats fell.

In this slide, you can see (on the left) that it was one of the most profitable businesses ever and was arguably overearning. Cable Network margins were amongst the highest in the economy. On the upper right, you can also see that people were paying for stuff they didn't use. This is data from Nielsen that that shows that in any given month, people were watching less than 10% of the networks that they paid for. And, on the bottom right, you see that cable price increases dramatically outstripped the CPI.

What happened, of course, is that internet came in, it unbundled information from infrastructure, and it caused the cost to move bits around to plummet. This graphic is meant to show the distribution moat getting shaky.

Netflix, as a proxy for all new video entrants, ran the whole disruption playbook. It started with deep library and then picked off kids and then unscripted, and today it is, I would argue, the most powerful company in Hollywood.

Let's talk about the aftermath of that disruption, which the industry is struggling with today. This is a snapshot of the video business in the U.S.: traditional, streaming, box office and home entertainment, all indexed to $1. I think a surprising thing here is the relative resilience of traditional TV. Despite all the talk about Netflix and Hulu and Disney+ and FAST and CTV and Roku and all that stuff, linear TV still represents 66 cents of every dollar that is spent on video in the United States.

But, as is well understood, the linear business is under tremendous pressure. So, I won't dwell on this. This chart on the upper left is a bit of an eye chart, but the purple line is the important one. It shows you pay TV penetration, which peaked near 90% a decade ago, which is before this chart starts, is now headed toward 50% of households. Linear viewing obviously has declined, as you can see on the right, other than sports. And the bottom chart shows that those declines have been the most dramatic among the youngest cohorts, which is obviously not a good leading indicator.

To offset this pressure on linear, all the big media companies launched their own streaming services, Disney+, Max, Peacock, Paramount+, and they have spent very heavily on content. You can see here content amortization is up a lot over the last five years, there's been an explosion of originals.

But streaming has not proved to be the silver bullet a lot of people hoped. On the upper left, you can see that sub growth has been slowing. The reason it's slowing is because of this chart on the upper right. Consumers seem to be kind of maxing out around four services per household, on average. That’s partly because some of them are using churn proactively, as a budget management tool. And so, as you can see on the bottom, churn is quite high and keeps going up. And that puts a lot of pressure on unit economics.

The most important and fundamental problem is this one: streaming just monetizes a lot less than pay TV. What this chart shows is the average pay TV household generates 3X as much subscription revenue and 7X as much advertising revenue as the average streaming household. On the ad side, that gap will close somewhat, because Netflix, Amazon and Disney have all added a lot of streaming advertising inventory, but even so, it will be very challenging for the gap to close all the way. This is something I’ve been writing about for the last, three, four years. The profit pool of streaming is just structurally smaller than pay TV.

The result of all of that is that video profits are down for the big media companies. What this chart is showing you is video revenue and EBITDA, for the largest media companies. In 2018, that was seven companies. Today it's five companies, but it's the same assets reconstituted.

So, this is all video—linear, streaming and studio, combined. Revenue is up a little bit, but profits are down 40%.

And of course, the big media companies’ stocks have suffered as a result.

So, let's talk about what happens next.

As I said, historically, there were these two big moats, a moat around distribution and a moat around content creation, or production. All of the things we're talking about are really the result of the distribution moat falling. When barriers to entry fell in distribution, new entrants came in and squeezed out excess profits. But all of the problems that exist in Hollywood today, in the broader entertainment business— whether it's reduced production, the RSNs failing, the writers and actors strike, why did Paramount sell itself? Why did Bob buyer come back?—all of these things are lagging indicators of the last disruption. All of the current challenges in the business are occuring essentially because there is just less money to go around.

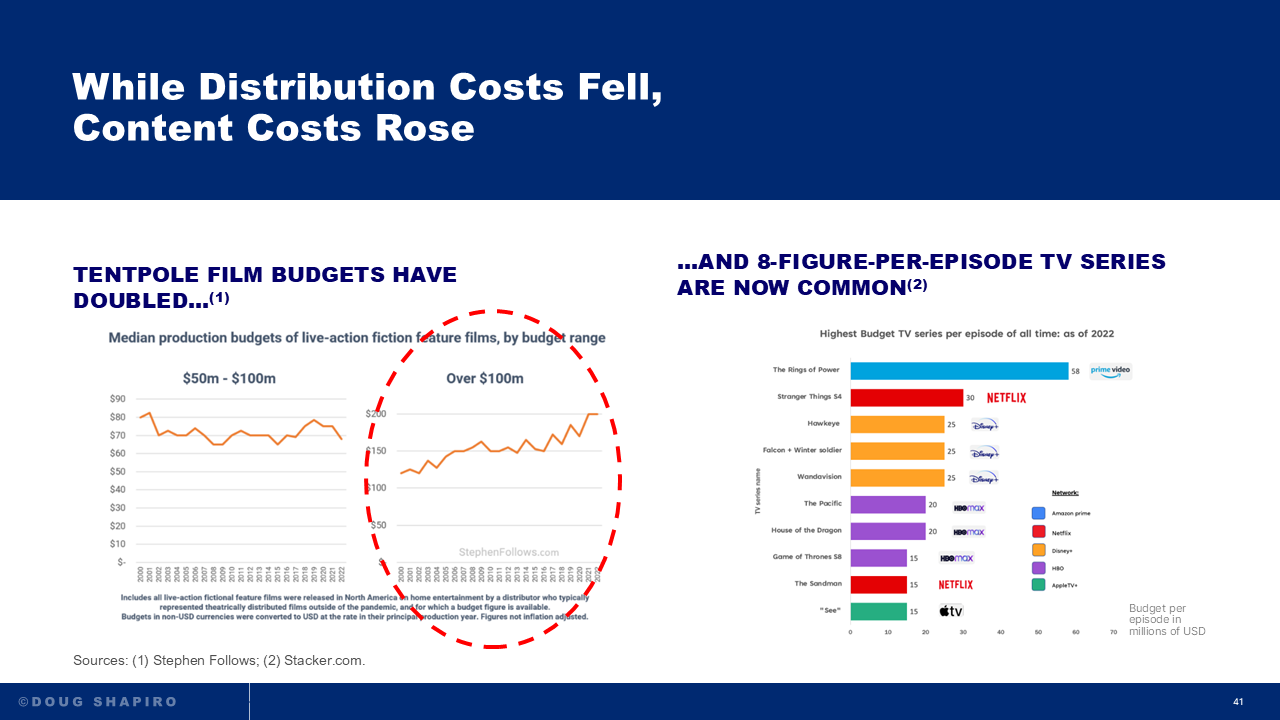

Because even as the barrier to entry around distribution fell, the moat around content creation actually got deeper and wider.

The reason is that even as the cost of distribution fell, content costs actually went up. You can see here that the cost for the median tentpole film doubled over 20 years. You can't quite see it here, but the cost for an hour of premium scripted TV doubled over about 10 years.

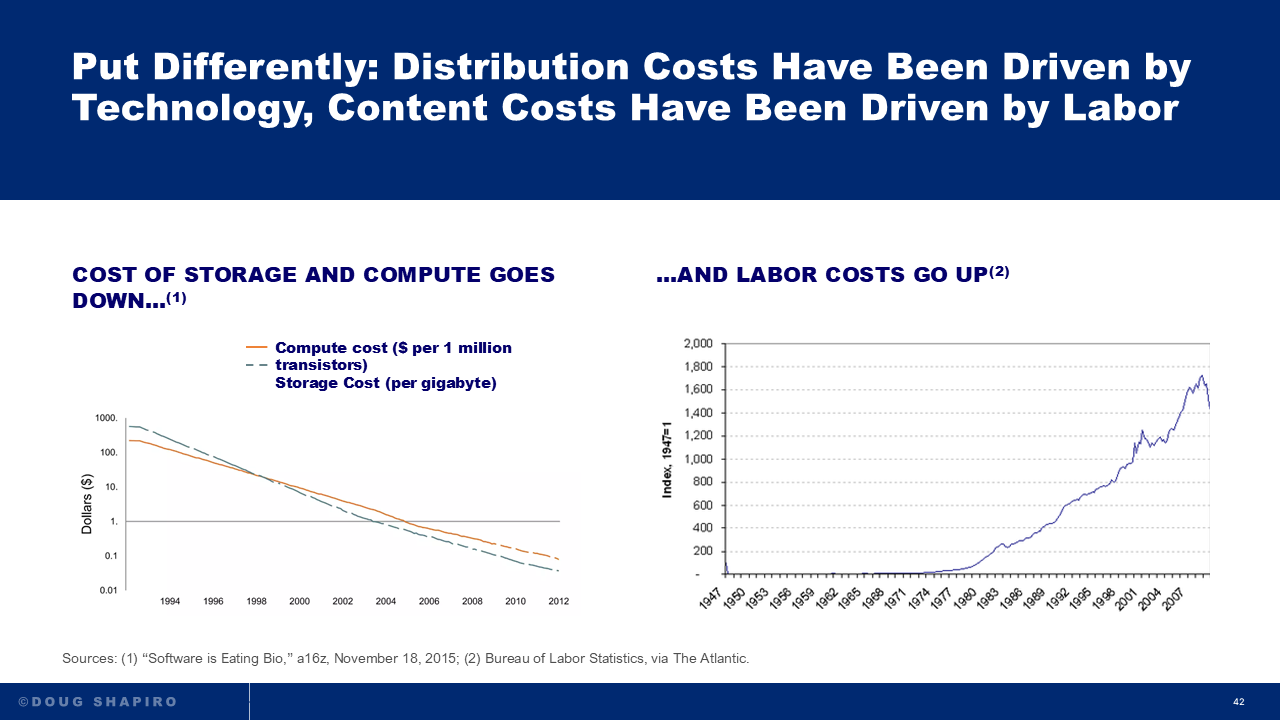

Or, another way to look at it is this, is that distribution was on a downward sloping, technology-driven cost curve, and content creation wasn't an upward sloping, labor-driven cost curve.

To put it differently, the left is Moore's Law, and the right is medical insurance premiums and sushi. And so the question becomes, what happens if Moore's Law comes for content creation, too?

That brings us, of course, to generative AI. I'm sure you've all seen the evolution of these models from the horrific images of Will Smith eating spaghetti 18 months ago to Sora and Minimax and Runway Gen-3 and Luma Dream Machine and all of the models that exist today, a new one of which seems to come out on a daily basis.

So, I'm not going to show you that, but I do want to show you some of the early commercial deployments, which I think are really interesting.

This is an ad for Toys R Us that was made using Sora, by an agency called Native Foreign. I will just play a part of it quickly. The point is that nothing here is real, it is all AI, and it shows how far we’ve come in such a short time.

This is a movie called Where the Robots Grow. It is billing itself as the first AI-enabled feature length animation, created by a studio called AiMation, and is 87 minutes long. They say that the team is only nine people, and it only cost $8,000 per minute. Of course, those are fractions of the labor and cost of a traditional animated production. One thing they very cleverly did is they use robots, so lip syncing is not that important. Is it Pixar? No. But might it be really entertaining if you're five or six? Yeah. And clearly we're getting closer. It's streaming for free on YouTube, and I encourage you to check it out.

And so, again, the big question is that you you have already have an industry that is back on its heels from the last disruption, and what happens if this other moat also comes down.

Just to be clear, I'm not arguing that we're going to see an AI generated blockbuster movie anytime soon. What I am saying is that if GenAI democratizes high quality content creation, it would just exacerbate the low-end disruption that's already happening from creator content. On the left, you can see data that I think a lot of people have seen before. It shows you that YouTube is by far the largest streaming service in the U.S. to televisions. So, this doesn't even capture PC and mobile. But you can see here that its share of streaming is larger than Disney+, Hulu, Peacock, Max, and Paramount+ combined.

On the right, what you can see here is a comparison of the viewership of Mr. Beast compared to the most popular shows on Netflix in the first half of last year. So, if you thought about Mr. Beast as a show, you would see that it is actually the most popular show in the world.

This is a redux of the disruption chart I showed before, for the next disruption.

Now you can see that Netflix goes from disruptor to disruptee. You see a visualization of the low-end disruption of professionally-produced content by creator content. It has already picked off the least demanding customers, kids. The most popular kids show in the world is CoComelon—on YouTube. The next least demanding customer is unscripted viewers, and the most popular unscripted show in the world, or maybe just show in the world, is Mr. Beast—on YouTube. And so the question is whether these tools (Runway, Sora, Flux, etc.) throw gas on the fire and enable creator content to continue moving up the performance curve?

I'm not saying that the sky is falling. I'm not saying that Hollywood is going away. What I am saying is that there is a risk that these models undermine the economic foundation of the business. I think for creatives, there’s less of a risk that Hollywood replaces you with AI; there's a much greater risk that AI undermines the economics of Hollywood and pressures their budgets and ability to pay you.

Just to hammer home the point, here's a recent movie made by just one guy, a five-minute short. His name is Dave Clark. I won't play the whole thing. But I think the the key to keep in mind here, and the thing I always think about when watching these kinds of films, is that these are the worst that these tools are ever going to be. This is called Battalion and I would also encourage you to take the five minutes and watch this on YouTube.

One more thing to consider is that GenAI won't only be used to make movies less expensively. It also has unique properties that will open up unique applications.

This is something I wrote about in my most recent post Gen AI Video as a New Form. Typically, when there's a new medium, the first thing it's used for is to imitate old media. The first radio broadcasts were just vaudeville and the first magazines online were just basically PDFs. But what happens over time is that the creatives learn to exploit the unique properties of the medium and do unique things, and I think that's going to happen with GenAI as well.

So, when you start to think about what GenAI can uniquely do, obviously it's going to be much less expensive, and so you're going to have much more risk and more experimentation with formats and storylines, you’ll have broader representation, it's going to open up fan creation in video. And then you get to a bunch of stuff that's kind of hard to get your head around, at least it is for me. Questions like, what does it mean that video can be rendered real time? What does it mean that all video is inherently three dimensional? What does it mean that it's unconstrained by physics?

I think it's going to take a while for creatives to figure out how to exploit those things, to see what actually takes hold with consumers. But the bottom line here is that just as social video changed the definition of quality in video, I think GenAI will do the same thing. And that will just open up a yet another new vector of competition with professionally-produced content, new bases of competition.

When you draw the parallel between this disruption and the last one, you see that this one could happen a lot faster.

One reason is just simply internet scale. As I mentioned before, Hollywood put out 15,000 hours of content last year, and there were 300 million hours uploaded to YouTube. What that means is that only a very small percentage of that needs to be competitive with Hollywood. I'm not saying comparable, just competitive for time, to be really impactful. Consider that if just 0.01% of that 300 million hours is considered competitive with Hollywood, that's 30,000 hours a year. That's twice Hollywood's annual output.

Another issue is that the last disruption required a huge lift in terms of infrastructure, both wireless and wireline broadband infrastructure. Consumers had to adopt broadband, they had to adopt streaming, they had to get connected devices to their TVs. All those things are now in place. So, if there was a great AI-enabled TV show released for free on YouTube, that could be the most popular show in the United States the next day.

The last point is that I think it's very hard for the studios to adapt to this. That's not a criticism of the studios, it's really a commentary on the structural challenges. Maybe most important, when you draw these parallels—between the disruption of content distribution and content creation—creating content is much more core to what they do than distributing it. That’s just going to add to the complexity. They're also very leery of any talent backlash, particularly after the strikes last last year. They're very leery of running afoul of some of these unresolved legal questions. And so I think it's just going to be a really, really challenging thing for the studios.

What Opportunities Will Emerge?

So, to finish up here and try to look at the at the light at the end of the tunnel. I think an important question is, well, okay, if you believe all this is happening, what opportunities will emerge? There aren’t easy answers here. But I think as a generality, the good news is that when one input into the production process becomes abundant, other things become scarcer and more valuable.

So what is scarce in a world of infinite content?

Obviously, good ideas are still quite scarce.

Distribution and curation will be more valuable than ever.

Proprietary technology, which is a very broad topic.

Consumer, time and attention is even more valuable. And keep in mind, linear TV still commands a lot of that.

First party data.

The ability to cut through the noise with with marketing.

Human authenticity and provenance, the backstory of content, I think, is going to become more important than ever.

The ability to create fandoms and community premium.

IP.

Libraries.

IRL experiences, especially sports.

And having talent relationships.

And, as shown, many of these things are accessible to traditional media companies.

So, I think this really is the challenge for everyone in the media business, to figure out what are the core competencies that they can lean into that become even more valuable as content becomes more abundant.

So, I will stop there. Typically, if I was giving this presentation live, we would now be able to discuss this, tease apart some of these issues and dig in deeper.

But even in the absence of that, I hope that you found this a good use of time.

Thank you.

Very Interesting piece thank you. I'm wondering how these new GenAI studios will monetize. Right now if you're a creator, YT monetization is clearly not enough, but you have other business models, mostly branded, to add $. But how about these GenAI studios? They probably won't be attractive to brands (there are not incarnated, no direct relationship with communities). So how will they sustain their work if platform monetization is still not enough for them? Community based monetization: subscription? tips? This will be only for the happy few probably.

I'm wondering what if they can't find a significant revenue stream like the creators did with branded content, what will happen will we see such an influx of new content like what we saw with creators/influencers?

let's see!

Outstanding piece. Probably the most interesting and insightful thing I've read all year. Echoing Ryan, incredibly interesting to see it laid out like this. Thank you for sharing this fantastic analysis and insight. I work in the Podcasting industry, so deeply understanding the meta trends and using this to extrapolate and explore what sorts of parallels could play out in our space is so valuable. Thank you.