Why Hollywood Talent Will Embrace AI

Precedent, Increasing Creative Control, and Hollywood's Woes

GenAI obviously has the potential to be extremely disruptive to media businesses in general and Hollywood in particular, but the speed and extent of this disruption hinge on a few critical unknowns. These include how far the technology will evolve and to what degree consumers will accept AI-enabled content, both of which I discussed in my last post (How Far Will AI Video Go?). Another is how and when the murky legal questions around GenAI will be resolved.

In this post I address another key unknown: whether talent will embrace it. That’s critical. Amid all the cool AI video demos, shorts, experiments, and fake movie trailers, it has remained very clear that AI video will only affect culture and the media business if people use it to produce compelling stories. Otherwise it’s just a parlor trick. But which people?

Talented people outside of Hollywood will unquestionably embrace it. There are probably tens or hundreds of thousands of “lost Einsteins” globally: creative and driven people who have an urge to create but either failed to make it in Hollywood or, more likely, never tried. I also think that there are thousands of people working in below-the-line jobs and around the periphery of Hollywood1—development, production management, talent representation, marketing, etc.—who got into the entertainment business to tell stories, but for whatever reason found themselves in adjacent roles. (Interestingly, so far, many of the creatives at the forefront of AI have come from creative agencies—storytellers who do brand work but have long itched to tell stories of their own.)

But what about established talent within Hollywood? Attracting talented, successful storytellers would accelerate the disruption and enable GenAI to reach its full potential. People often talk about “Hollywood” as some monolithic thing, but of course it’s not. The studios and talent have long been in an uneasy codependent relationship, a combination of aligned and misaligned interests. Each desperately needs the other, but they share a mutual distrust and often clash over creative control, credit, and, of course, money. That tension boiled over during the strikes in 2023 and a lot of ill will remains.

In Hollywood, there has been a lot of vocal antipathy toward AI. But the ice is starting to thaw. Over the next year, I believe that many more Hollywood creatives will embrace it—including household name directors, writers, and producers—for three reasons: precedent, the continued progression of creative control in AI, and, most important, the problems in Hollywood will push them that way.

Tl;dr:

Many in Hollywood have spoken out against AI, but some high-profile writers, directors, and producers are publicly endorsing it, with many more privately experimenting. Over the next year, I expect many more to emerge.

There is a long history of creatives first rejecting new technologies as somehow undermining or bastardizing art, but then embracing them. In Hollywood, prior villains have included talkies, the DVD, and CGI.

The deep learning models that power GenAI are massive, opaque, and hard to control. But commercial AI video and tool providers and the open source community are working hard to give professionals the fine-grained control they need. A non-exhaustive list of these efforts includes: training models with a richer understanding of visual terminology for more precise prompting; enabling conditioning of video models with both images and video; post-generation editing tools; ControlNets; fine-tuning; node-based editors; keyframe interpolation; and integration into existing edit suites/API support, among others.

Perhaps most important, the challenges in Hollywood are inadvertently pushing creatives toward AI. With 2024 in the rearview mirror, it’s now clear that peak TV is truly over. Neither production activity nor spend bounced back from strike-depressed levels in 2023. From here, overall video content spend is unlikely to grow faster than video revenue—which is to say, not much. At the same time, rising sports rights and a mix shift toward acquireds will put even more pressure on original content. Tack on studios’ growing risk aversion and the path toward telling original stories in Hollywood is narrowing.

Many talk about AI as a democratizing technology, but for some established talent it may be a liberating technology too.

For a lot of people in Hollywood, AI still feels like a distant concern. As more talent embraces it, it will take on more urgency.

The Ice is Thawing

Many artists have spoken out against AI.

During the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes in 2023, Justine Bateman was one of the most vocal, saying that AI is “not about solving problems for people. It’s about money. It’s about greed…” She also advocated for “[n]o generative AI in the entertainment industry, period.”

Glenn Close, Robert Downey Jr., and Scarlett Johansson are among the boldfaced names who have also raised concerns. Here’s Nicolas Cage:

“I am a big believer in not letting robots dream for us. Robots cannot reflect the human condition for us. That is a dead end if an actor lets one AI robot manipulate his or her performance even a little bit, an inch will eventually become a mile and all integrity, purity and truth of art will be replaced by financial interests only. We can’t let that happen.”

These are all actors, who have a lot to lose if synthetic actors eventually become viable. Fewer directors or showrunners have gone on record, although a few months ago Guillermo del Toro offered up this zinger:

“A.I. has demonstrated that it can do semi-compelling screensavers. That’s essentially that…. The value of art is not how much it costs and how little effort it requires, it’s how much would you risk to be in its presence? How much would people pay for those screensavers? Are they gonna make them cry because they lost a son? A mother? Because they misspent their youth? F*ck no.”

Many believe that art and creativity are intrinsic to what makes us human and neither can nor should be the domain of machines.

This wariness or hostility—whether motivated by fear, skepticism, or ideology—is understandable. AI legitimately threatens to reduce or eliminate some (or possibly many) jobs. AI video has produced a lot of cool experiments and even a few commercial applications, such as ads and music videos. But it has yet to have its “Toy Story moment”—that bolt-from-the-blue project that comes from outside the system, shows the potential of the technology, and shakes up Hollywood. (I think this will happen, but it hasn’t yet.) It also still has a lot of noticeable flaws, most important that it hasn’t yet crossed the uncanny valley. AI humans still feel “off,” robotic, often creepy. Perhaps most fundamentally, many believe that art and creativity are intrinsic to what makes us human and neither can nor should be the domain of machines.

But the ice is starting to thaw. The highest-profile signal yet is James Cameron joining the board of Stability AI, a few months ago. The Russo brothers, filmmakers behind some of the most successful MCU films, are building an AI studio. A few weeks ago, Pouya Shahbazian, producer of the Divergent films, launched Staircase Studios, which aims to use AI to create 30 films over the next four years, using human actors and writers (and paying them union scale wages). Lorenzo di Bonaventura, who produced the Transformer films, is an adviser. James Lamont and Jon Foster, two-thirds of the writing team behind Paddington in Peru, will team up to write a full-length version of the AI-animated short Critterz.

I’m aware of many other household names who are also experimenting with AI. Over the next year, I expect that more well-known creatives will publicly embrace it.

Let’s talk about why this is inevitable.

Creatives Often Reject, and Then Embrace, New Technologies

There is a long (long, long) history of creatives initially rejecting new technologies as somehow cheapening or bastardizing the creative process. This was true even of the Gutenberg printing press. Johannes Trithemius, a German monk, famously criticized printing in his 1492 manuscript, De Laude Scriptorum ("In Praise of Scribes"):

“Printed books will never equal scribed books, especially because the spelling and ornamentation of some printed books is often neglected. Copying requires greater diligence.”

This almost reflexive rejection can be traced through every technological innovation in media.

Since the topic is Hollywood, let’s stick with film. At the advent of “talkies” in the late 1920s, Mary Pickford, co-founder of United Artists and silent film actress, supposedly said '“Adding sound to movies would be like putting lipstick on the Venus de Milo.” Charlie Chaplin added that “Talkies are spoiling the oldest art in the world—the art of pantomime. They are ruining the great beauty of silence.”

In 1982, Jack Valenti, Chairman of the Motion Picture Association of America, testified in Congress in favor of bills to ban the VCR:

“[T]his property that we exhibit in theaters, once it leaves the post-theatrical markets, it is going to be so eroded in value by the use of these unlicensed machines, that the whole valuable asset is going to be blighted. In the opinion of many of the people in this room and outside of this room, blighted, beyond all recognition…I say to you that the VCR is to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston strangler is to the woman home alone.”

When renowned visual effects artist Phil Tippett, who specialized in stop-motion animation, first saw computer generated imagery (CGI), he says his reaction was “I’ve just become extinct.”

All eventually embraced what they initially rejected. Pickford went on to star in talkies; Chaplin’s most commercially successful film was The Great Dictator, his first sound film, which was nominated for five Academy Awards; the VCR birthed the home entertainment market, which at its peak in the mid-2000s was almost three times as big as the theatrical box office; and Tippett won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects for overseeing the CGI work on Jurassic Park.

It’s easy to anticipate the pushback here and why AI is different. None of these technologies replaced the humanity in the art—they just changed the way that art is expressed or monetized. That is true. But AI doesn’t necessarily eliminate human artistry either.

The Progression of Creative Control

Last year, author Ted Chiang wrote a takedown of GenAI in an essay in The New Yorker titled “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art,” arguing that “to create a novel or painting, an artist makes choices that are fundamentally alien to artificial intelligence.” The operative word is choices. This criticism, and, for that matter, a lot of criticism of AI (including del Toro’s quote above) is based on a common misconception or gross oversimplification: that using AI definitionally means giving up the ability to make creative choices.

In the first iterations of most GenAI tools, they necessitated giving up creative control.

One reason for this misconception is that in the first iterations of most GenAI tools, it was mostly true. Most were zero-shot: you put in a prompt and a fully-formed (and mostly soulless) poem, story, essay, image, video, or song belched out the other end. Creatives had very little control. But that wasn’t a design choice, that is a function of how these models work. They are extraordinarily complex, so it is almost impossible for a person to understand what they are doing and, likewise, it is hard for a person to control their output.

Clearly, the set of use cases for which it makes sense to delegate all creative decisions to an AI is necessarily a subset of the number of cases in which it makes sense to only delegate some.

That’s a problem. For one thing, it’s very limiting. Clearly, the set of use cases for which it makes sense to delegate all creative decisions to an AI is necessarily a subset of the number of cases in which it makes sense to only delegate some. It might do the trick for stuff that is formulaic, short, purely informative, or perhaps the high-calorie, low-nutrient junk food of the internet, but that’s not most stuff. (It’s kind of like asking: could you make a tasteless brown food brick that contains most necessary macronutrients? You could, but that’s not usually the criteria people use when choosing food.) It won’t work for any creative use case for which the humanity, craft, provenance, or backstory matter—in other words, most stuff.

For another, professional creatives expect and need control. To address this limitation, providers of proprietary AI video models and tools and the open source community are hard at work trying to provide finer-grained creative control. Staying on top of all these advancements is essentially impossible, especially when you consider all the activity in open source, which is effectively continuous. Instead, let’s talk about how creative control will improve conceptually. Here’s a non-exhaustive list.

Richer understanding of visual language for more precise prompting. Developers are providing video generation models a richer understanding of the terminology associated with visual styles, lighting, angle, camera lenses, depth of field, film stock, textures, and camera motion, etc., which enables creatives to use more technically precise prompts. This has been achieved in part by training models on video that has been annotated with richer metadata and through “manipulation in the latent space.” (Without getting into the technical details, in this context the latter means learning which parameters are associated with different visual elements post training and then manipulating these parameters during inference.) As an example, check out the new MiniMax T2V-01-Director Model below.

Image-to-video/video-to-video pre-conditioning. Many models, like Kling, Runway Gen-3, Veo 2, MiniMax, HunyuanVideo, and Sora, make it possible to provide a conditioning image in addition to the text prompt (although some are better at it than others). That could be a photograph, digital art, the output of an AI image generation model, or even hand drawn images. As described above, video diffusion models are guided by a text prompt. In the case of image-to-video models, the control image is processed as another type of embedding (a “visual conditioning” embedding). When the model generates video, it is guided by both the text prompt and the conditioning image. Similarly, some models also support video-to-video. In this case, the model uses the entire video clip as a conditioning input, where each frame of the reference video guides the generation of each corresponding frame in the output video.

Guidance weight. Many commercial models that support multiple conditioning inputs also give users flexibility how much to weight those inputs, such as through sliders or dials. For instance, an image-to-video model might include a slider that enables the user to dictate how much the model maintains fidelity to the reference image vs. the prompt.

Post-generation edits. Some models also make it possible to regenerate part of a video with guidance from the user after it has been generated, with features like in-painting, masking or brushes. In masking, for instance, the creator can mask off a portion of the video, put in a text prompt, and the model applies that text prompt only to the masked portion of the image. That makes it possible to edit a video without regenerating the whole thing. Runway offers the widest array of brushes and masks.

ControlNets. ControlNet-style approaches, which are currently only available with open source models (like Stable Diffusion and Flux), are a more specialized form of conditioning. For instance, they allow control channels for depth (MiDaS), edge detection (Canny), and pose information (OpenPose)—similar to how ControlNet works for images. This allows users to precisely guide how characters move or how scenes are structured spatially during inference.

Fine-tuning. It’s also possible to fine-tune models by conditioning them with small, specialized datasets. These might include specific people, artistic styles or products. This is also prevalent in open source, where the current state of the art technique is called LoRA, or Low Rank Adaptation. (Runway is also working with Lionsgate to create models fine-tuned on Lionsgate’s IP.) LoRA influences the generation process by making slight adjustments to the model, allowing it to “remember” specific elements from the fine-tuning dataset without retraining the whole model.

Node-based editors. Node-based editors are visual, modular interfaces that are commonly used in graphic design and VFX. They break down the video generation process into multiple steps (separate “nodes”), each of which can be precisely controlled (see the sample below). For instance, they make it possible to adjust prompts, include negative prompts, re-scale images, choose among different AI models, include ControlNets, add LoRAs, etc., and adjust the weights of all these different components. For now, they are more prevalent in open source, led by ComfyUI, but a new workflow tool called Flora enables node-based design with support for commercial models.

Keyframes (frame interpolation). Some models also support uploading multiple images of a scene and then interpolating the motion between them, like Sora and Luma’s Dream Machine. For example, this might include a character on one side of the room in one frame and sprawled out on the other side of the room in another, and the model would try to smoothly interpolate the motion between keyframes.

Multi-modal coordination (audio synchronization). This entails training models with explicitly aligned audio-visual datasets. One of the main challenges with AI models today is naturalistic looking speech, especially lip sync. By training models with datasets of people speaking and the corresponding audio tracks, the model learns to pair subject movements with corresponding speech waveforms. Hedra recently released its Character-3 model, which creates video from a reference image and voice, syncing the voice track with facial and head movements and body gestures. Runway’s Act One (shown below) allows the user to sync up the facial movement and speech from reference video with an image, thereby animating the image.

Hybrid workflows. Professionals are increasingly developing their own proprietary combination of tools: like starting with Imagen or Midjourney for image generation, then Kling, MiniMax, or Veo 2 for different elements of the video generation, then upscaling via Topaz, then voice generation using Eleven Labs, etc. The flexibility to mix and match tools is another source of control.

Integration into existing edit suites/API support. Integrating AI video generation models into existing edit suites will flatten the learning curve for professional editors, who use those tools every day. It will also make it a lot easier to integrate real footage with AI elements seamlessly. (Incidentally, that will make it increasingly hard for viewers to tell what’s AI and what’s not.) Last year, Adobe demoed the idea of including support for third-party plugins in Premiere Pro and After Effects (and they recently struck deals to support image generation tools from Black Forest Labs, Google, and Runway in some products). Blackmagic Design has also announced plans to integrate video generation tools into DaVinci Resolve. Stability AI offers API access to their video models, allowing developers to build custom interfaces and integrate generation capabilities into specialized workflows. Pika and Runway similarly provide API access that lets technical teams build custom interfaces or plug into existing editing software.

For an auteur who will only adopt AI if it is as versatile as physical production, will all that collectively be enough? Probably not yet. But with the collective resources of Google, OpenAI, Adobe, Runway, Tencent, and the open source community, among others, all marshalled toward providing creatives more control, we’re heading that way. For AI-curious professionals who are willing to adapt their workflows, we’re getting very close.

Hollywood’s Woes May Leave Little Choice

To use suitably cinematic language, Hollywood’s problems are also inadvertently driving creatives into the waiting arms of AI.

There has always been tension between studios and talent. In a moment of candor, even some of the most successful writers, directors, showrunners, and producers will admit they’d like to reduce their reliance on the big studios. Working with the studios has always required tradeoffs.

Since making film and TV is expensive and the studios put up most or all of the money, they (understandably) exert a lot of control. They often weigh in or override creative decisions. They may kill projects for seemingly capricious reasons or option IP and keep it stuck in perennial development hell. They may shift distribution or marketing strategies in ways that disadvantage films and series that creatives believe deserve better. They’re also (again, understandably) stingy with profit participations, other than for the top 0.1% of talent. The economics of TV production, in particular, have deteriorated in recent years. Historically, creatives retained substantial upside if a show hit, but the shift to cost-plus models (in which the licensee takes on all the risk and keeps most or all of the upside) has meant that creatives no longer benefit to the same degree from a successful show.

Lately, however, it has gotten even harder to work in Hollywood, especially for anyone other than top talent, and it is unlikely to get much better. Many people talk about AI as a democratizing technology, but for some Hollywood creatives, it could prove a liberating technology too.

Many people talk about AI as a democratizing technology, but for some Hollywood creatives, it could prove a liberating technology too.

TV Has Well and Truly Peaked

One of the clear lessons of 2024 is that peak TV is over. Owing to the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes, production activity declined markedly in 2023. One of the surprises of 2024 was how little it bounced back. Here are a few charts to underscore the point. Figure 1 shows that U.S.-produced TV premieres actually declined in 2024 from 2023.

Figure 1. U.S.-Produced Premieres Fell Last Year

Source: Luminate.

That could reflect the lingering effect of lower production activity in 2023—since production ground to a halt in 2023, fewer shows were ready to premiere in 2024. But there are other discouraging signs. Figure 2 shows data from ProdPro, illustrating that while production activity increased in 2024 from 2023, it was still well below 2022 levels.

Figure 2. Production Activity Bounced Back in 2024, But Still Well Behind 2023

Source: ProdPro

Now that financial reporting for 2024 is complete, we can also look at spending levels from the biggest producers. Sometimes, trade publications and data providers track book content spend, but that can be deceptive. Book content costs are largely driven by amortization of spending in prior years and are therefore a lagging indicator. Cash spend is a more accurate reflection of current production activity.

As shown in Figure 3, I estimate that cash spend for Amazon, Apple, Disney, Fox, NBCU, Netflix, Paramount, and WBD fell by $18 billion in (fiscal) 2023 and barely bounced back in 2024. Figure 4 shows that after several years of elevated spending levels, cash content spend is reverting back to historical levels of roughly 50% of total video revenue. With all the media conglomerates focused on profitability and the management of both Amazon and Apple reportedly pushing for development execs to rein in spending growth, there is little reason to think that programming spend will grow faster than video revenue for the foreseeable future.

Cash content spend is unlikely to grow much from here.

Feel free to pick your own forecast for industry revenue growth, but for reasons I’ve explained before (see Video: Forecast the Money), I estimate that it will roughly be flattish or, if up, only marginally. As a result, total cash content spend is unlikely to grow much from 2024 levels.

Figure 3. Cash Spend Didn’t Recover Much in 2024 Either

Notes: Global content figures reflect the combination of Amazon (Prime Video original and acquired only), Apple (TV+ only), CBS (pre-Viacom merger), Discovery (pre-WBD merger), Disney, Fox, NBCU (ex. Sky), Netflix, Viacom/ViacomCBS/Paramount and Warner Bros. Discovery. Does not adjust for non-calendar fiscal years (Disney is September, Fox is June). Sources: Company reports, Author estimates.

Figure 4. Cash Content Spend Has Reverted to ~50% of Video Revenue

Notes: Video revenue is combination of linear, streaming and studio. Video and global content figures reflect the combination of Amazon (Prime Video original and acquired only), Apple (TV+ only), CBS (pre-Viacom merger), Discovery (pre-WBD merger), Disney, Fox, NBCU (ex. Sky), Netflix, Viacom/ViacomCBS/Paramount and Warner Bros. Discovery. Note that it assumes no incremental revenue for Amazon (assumes all Amazon Prime subscribers get Prime Video) Does not adjust for non-calendar fiscal years (Disney is September, Fox is June). Sources: Company reports, Author estimates.

Originals Spend Will Probably Fall

Within this envelope of roughly flattish overall content spend, spend on originals will probably fall. That’s because of both rising sports rights costs and a shift in favor of acquireds over originals.

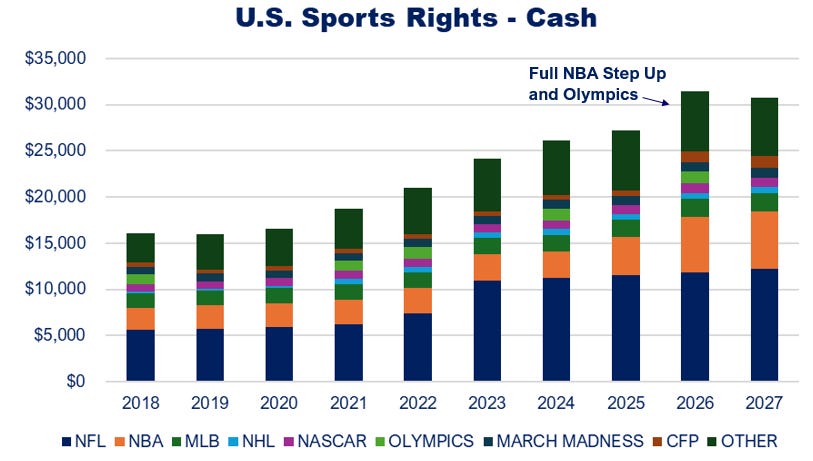

Figure 5. Sports Rights Likely to Increase Substantially in 2026

Sources: Public reports, Author estimates.

As shown in Figure 5, I estimate that cash sports rights costs are set to climb by $5 billion in 2026, owing to the impact of the 2026 Olympics and the first full year of the new NBA contract, plus normal contractual escalators. That funding will need to come from somewhere, with originals the most likely candidate.

Acquireds are a much better bet and the conglomerates are now more willing to license to competing streamers.

It is also likely that non-sports content spend shifts toward acquired and away from originals. Originals have always been a tough bet, but there are arguably signs that the ROI on original programming is in decline. Figure 6 shows Luminate data, illustrating that on most streaming platforms, 2/3 or more of originals viewing comes from the top 20 original seasons on the platform. Since that doesn’t distinguish between seasons of the same series, originals viewership is probably even more concentrated in the top series. (I wrote about why this is happening in Power Laws in Culture.) Very few originals pay off.

Figure 6. Most Originals Viewing Comes from Few Shows

Sources: Luminate, via Variety VIP+.

A big surprise in 2023 was the so-called “Suits phenomenon.” NBCU licensed Suits, a middle-of-the-road performer on the USA Network from 2011-2019, to Netflix. It went on to become a huge hit for Netflix and the most streamed show of 2023. To put it in perspective, according to Nielsen, that year Suits generated 58 billion minutes, more than four times as much as Netflix’s most-watched original that year, The Night Agent.

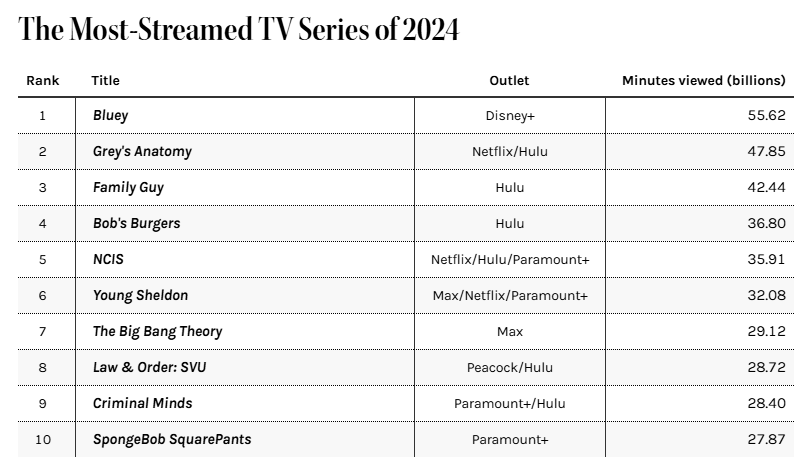

But it’s not just Suits. As shown in in Figure 7, a growing proportion of streaming viewing is coming from acquired content. Here, you can see that among the top 100 most streamed titles each quarter, 80% are now acquired. In Figure 8, you can see that other than Bluey2, all of the other top 10 most streamed titles last year previously aired on other networks.

Figure 7. Acquired Content is Taking a Growing Share of Viewing

Sources: Nielsen, MoffettNathanson.

Figure 8. The Top 10 Most Streamed Series of Last Year Were All Acquired, Other than Bluey

Sources: Nielsen via Hollywood Reporter.

The growing dominance of acquireds coincides with growing willingness by the media conglomerates to license their content to competing streamers. As shown in Figure 9, 2023 was a turning point in the conglomerates’ approach to licensing. Over the last few years, as the big media companies have turned their focus to profitability, all have also shifted strategy away from retaining exclusive rights to their content and toward selectively licensing. In recent earnings call, all doubled down on the view that licensing (judiciously) makes sense.

With growing evidence that the ROI on acquired content is far better and the conglomerates all loosening up their grip on their libraries, content budgets will likely shift toward stuff that has already been made, not making new stuff.

Figure 9. 2023 Was a Turning Point in the Conglomerates’ Willingness to License

Sources: Company reports.

Hollywood is Risk Averse

So: aggregate budgets are unlikely to go up much; there will likely be a shift within budgets towards sports and acquireds; and, to top it all off, within the pool of money left over for originals, Hollywood is also becoming more risk averse and less willing to bet on original stories.

I won’t belabor this, because everyone in Hollywood feels it: the studios are taking fewer chances. The term most associated with mid-budget films is “dying.” Mid-budget comedies in particular have all but disappeared. Despite their prevalence at the Academy Awards, independent film is also struggling as the studios reduce acquisition budgets.

But to put some numbers around it, according to Ampere Analysis, in 2024 more than two-thirds of the top 100 movies and shows were based on existing IP. In September, producer David Beaubaire released a study about Hollywood development activity, showing that for the 505 major studio films greenlit for release between 2022-2026, only 10% were from internal development. The other 90% were either external packages (i.e., came with talent attached); sequels, remakes, or based on established IP; distribution of third-party projects or of the studios’ internal specialty arms. In other words, there are very few new stories emerging from the majors. If you are a creator and have an original idea, AI makes it possible to tell stories that Hollywood will no longer finance.

AI makes it possible to tell stories that Hollywood will no longer finance.

Getting More Real

To a lot of people in Hollywood, AI still seems theoretical and, if a risk, a distant one. But if established talent starts to embrace it, that risk will probably feel a lot more clear and present. I think that will happen for all the reasons above: the historical precedent is clear; the tools themselves are rapidly improving to provide the control that professionals demand; and the traditional pathways for telling original stories are narrowing.

For the industry, the question about AI is rapidly shifting from “if” to “what to do about it.”

This may sounds like a lot, but according to a report last year, there are over 500,000 people employed in the U.S. television, film, and animation industries.

Bluey is also technically acquired, since Disney acquired the international streaming rights from the Australian Broadcasting Corp. and the BBC, but it has not previously aired in the U.S.

Totally agree with all of this! I started my tech career at Netflix and have been making tools for storytellers ever since and am married to one. I love em!

Underneath all the salient frustration with AI is an undercurrent of frustration with the gatekeeping of Hollywood, as it's assaulted by UGC platforms like YouTube and TikTok and hollowed out by increasing competition for entertainment.

We've been starting at the other end of the spectrum -- hobbyists and YouTube creators -- before working our way up to the needs of professional filmmakers, but it might be worth checking out the Possible Studio (thepossible.io). Cheers!

I love this newsletter. Not only do I get the political, sociological and cultural context on evolving AI filmmaking, I get a nice summary of what the most current tools and workflows are