Video: Follow the Money

A Holistic View of the U.S. Video Value Chain and Some Surprising Insights

You might think that sizing the market for an industry is relatively straightforward. But that’s often not true, for reasons that include: 1) lack of data; 2) no authoritative source of data; and 3) no consensus definition of what constitutes the industry.

Let’s take music. The IFPI (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry) is the authoritative source for recorded music revenue globally (Figure 1), so that’s good. Even so, this is an incomplete picture of the music industry, because it excludes music publishing, live events and merchandise. For that matter, depending on the goals for the market sizing, “music” may be the wrong definition. Perhaps it should be “audio,” and include terrestrial radio, satellite radio, podcasting and audiobooks?

In this post, I provide a holistic view of the video value chain in the U.S. This includes both the buildup of total video revenue (where it comes from)—including traditional TV, streaming, selected short form (YouTube), box office and home entertainment—and the breakdown to determine how those revenues are then disbursed between distributors, packagers/producers and IP rights holders (where it goes to).

I’ve been in and around the TV business for a long time, but this analysis produced some conclusions that I think are non-obvious (at least they weren’t obvious to me):

The consensus narrative in TV is that streaming is the future and pay TV is the past. While that may be true, the relative numbers may surprise. For every $1 that consumers and advertisers spent on video in the U.S. last year, $0.66 went to traditional TV (pay TV and broadcast). For comparison, all streaming (SVOD, AVOD, FAST and CTV) only represented $0.21. Box office arguably gets too much mindshare; it was only $0.04 of every $1.

For the last several years, aggregate video revenue hasn’t grown on a nominal basis. The growth of streaming is coming entirely at the expense of traditional TV, theatrical and home entertainment. The open question is whether video revenue is currently in a transitionary period and will eventually resume growing, much like the trough that music exhibited from 2005-2015 (Figure 1).

Not only has overall video revenue been flat, but in recent years both consumers and advertisers have implicitly kept their expenditures on video pretty constant too, despite a lot of moving pieces (cord cutting, linear ratings declines, growth in streaming subs, new ad tiers, growth in CTV and FAST, etc.).

This stability means that consumer video spend has declined as a proportion of PCE and video ad spend has declined as a percentage of total U.S. ad spend. Had both kept pace over the last four years, the total video business would be 35% larger than it is today.

Video distribution isn’t a great business (for pay TV distributors, movie theaters, retailers, etc.). For every $1 of revenue, last year distributors took $0.23 off the top, but only kept $0.01 as operating profit.

Media companies spend a lot of money on content. For every $1 of revenue last year, $0.77 was remitted to them by distributors and, of that, almost 2/3 went to programming—$0.40 to entertainment programming and $0.10 to sports rights.

This 4X disparity between entertainment and sports spend shows why we probably aren’t in a sports “bubble,” particularly for premium sports, despite the pressure on traditional TV. Entertainment spend will likely continue to be reallocated towards sports for several reasons: sports programming is dramatically outperforming entertainment in viewership; it commands a disproportionate and rising share of both advertising and affiliate fees; the relative risk of producing entertainment content is rising; and, longer-term, GenAI may both reduce entertainment production costs and increase the relative scarcity of sports.

The TV ecosystem has undergone a significant transition over the last decade—and may possibly be on the precipice of another one, propelled by advances in GenAI. But the resilience of traditional TV and the overall stability in the consumer and advertiser video “wallet” both strike a somewhat hopeful note. Sometimes things aren’t changing as radically as we perceive.

Figure 1. The Authoritative Source for Recorded Music Revenue

Source: IFPI.

Where Does the Money Come From?

I set out to build up aggregate video revenue in the U.S., but let’s start with some definitions and nomenclature. As shown in Figure 2, “video” comprises traditional TV (pay TV and broadcast delivered by facilities-based providers, virtual MVPDs and over-the-air), streaming (SVOD, AVOD, FAST and CTV), short form (which here is only YouTube domestic advertising, more on that in a moment), box office and home entertainment (physical and digital rentals and purchases). To be clear, video revenue includes both what I’m calling “direct consumer spend” (subscriptions and transactions) and advertising, as can be seen in the table.

Figure 2. The Total U.S. Video Market is About $230 Billion

Source: Kagan/S&P Capital IQ, MAGNA, MoffettNathanson, OMDIA, Box Office Mojo, DEG and Author estimates.

The rationale for including YouTube is that it is increasingly viewed as a substitute for traditional video, both by consumers and advertisers. It is generating significant watch time on televisions and attracting both brand and performance advertising. By contrast, other short form video, such as Facebook/Instagram Reels and TikTok, doesn’t generate much or any watch time on TVs and predominantly attracts performance advertisers. So, in my view it’s (more) debatable whether they should be included as part of the “video ecosystem.”

The other challenge is that neither Meta nor TikTok regularly disclose revenue. But, for reference, here are some estimates. In 2Q23, Meta disclosed that Reels had achieved a $10 billion revenue run rate. Assuming it generated a little less in 1Q and more in 3Q and 4Q, let’s say it was $11-12 billion last year. Since roughly 40% of Meta overall revenue is in the U.S., let’s assume that was ~$5 billion domestically last year. The Financial Times recently reported that TikTok surpassed $16 billion in U.S. revenue last year. So, should you choose to include it, together Reels and Tik Tok probably add another ~$20 billion to the pie.

All of what follows assumes the inclusion of YouTube and exclusion of other short form (although the inclusion of TikTok and Reels wouldn’t change the story much). With that squared away, looking at both the waterfall build for last year and the time series of these data yields a couple of conclusions.

Traditional TV is Still $0.66 of Every $1

The popular narrative around the video business is that pay TV is dying, home entertainment is all but dead, box office is stagnant and streaming is growing rapidly. All of that is directionally accurate, but the relative sizes of these different components is often overlooked.

Figure 3 shows the waterfall video revenue build in the U.S. for 2023, both the absolute numbers and then indexed to $1. As shown, traditional TV (pay and broadcast) is still by far the largest component of the U.S. video market, or $0.66 for each $1 consumers and advertisers spend on video. For all the press and investor focus on Netflix, Disney+, Max, Roku, Pluto, Tubi, Peacock, Paramount+, etc., all SVOD, AVOD, FAST and CTV subscription and advertising revenue combined only represents $0.21 of every $1 spent. Box office also arguably gets a disproportionate amount of mindshare, representing only $0.04 of every $1.

Figure 3. Pay TV is By Far the Largest Component of Video

Source: Kagan/S&P Capital IQ, MAGNA, MoffettNathanson, OMDIA, Box Office Mojo, DEG and Author estimates.

All of streaming (SVOD, AVOD, FAST and CTV) is only $0.21 of every $1 spent on video in the U.S. Theatrical is only $0.04.

Video Revenue Hasn’t Grown in Recent Years

In a recent post, I showed that media revenue isn’t growing globally on an inflation-adjusted basis. This analysis shows that, in the U.S., total video hasn’t grown nominally in recent years.

In One Clear Casualty of the Streaming Wars: Profit (written more than three years ago), I made the point that, contrary to perception, streaming wasn’t actually growing the video pie. This analysis underscores that, showing that over the last few years, the growth in streaming and short form has come entirely from traditional TV, box office and home entertainment. This share shift can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The Growth of Streaming Has Come at the Expense of Everything Else

Source: Kagan/S&P Capital IQ, MAGNA, MoffettNathanson, OMDIA, Box Office Mojo, DEG and Author estimates.

It is an open question whether the current period represents a transitionary period and video will eventually resume growing, much like the trough that music faced from 2005-2015 (Figure 1). It’s possible. The pace of linear TV declines may slow as the subscriber base compresses on the most loyal households. At the same time, streaming monetization is climbing as the industry reverses its initial efforts to prioritize subscriber growth over profits and instead institutes price increases, clamps down on password sharing and pushes harder into advertising. For now, whether or when the growth in the latter offsets the decline in the former is anyone’s guess.

The Consumer and Advertiser Video “Wallets” Haven’t Changed Much

Another interesting observation can be drawn from Figure 5. It shows that the distribution of revenue between direct consumer spend (subscription and transactions) and advertising hasn’t changed (and, since the nominal value of total video revenue hasn’t changed much either, nominal direct consumer spend and advertising have both been pretty stable).

I found this surprising. Keep in mind that there are a lot of moving pieces in here: pay TV subscription revenue is falling due to cord cutting; traditional TV advertising is also falling because of rapidly declining ratings; box office has yet to re-achieve its pre-COVID high water mark (in 2019); home entertainment falls every year; streaming subscription revenue is growing due to growth in subs and, more recently, price increases; and streaming/YouTube advertising is also growing rapidly due to growth in viewership, more inventory as more SVOD providers introduce advertising tiers, the growth of CTV and FAST usage and more agency and advertiser familiarity with these channels. Nevertheless, the net effect of all this movement is that the amount that both consumers and advertisers spend on video hasn’t really changed.

Despite a lot of moving pieces, the amount that both consumers and advertisers spend on video has remained remarkably stable.

Figure 5. The Amount Consumers and Advertisers Spend on Video is Stable

Source: Kagan/S&P Capital IQ, MAGNA, MoffettNathanson, OMDIA, Box Office Mojo, DEG and Author estimates.

An alternative way of looking at the consumer component of the data is to calculate the average direct spend per U.S. household monthly, which can be seen in Figure 6. (Again, “direct consumer spend” is all the spending on subscriptions and transactions, and excludes advertising.) It shows that the average household spends about $90 monthly on video, a number that hasn’t changed much recently. I very much doubt that most consumers have a spreadsheet tracking their monthly video spending, but they are somehow managing to a pretty flat video “wallet.”

Figure 6. U.S. Households Spend About $90 on Video Monthly

Note: * Direct spend includes subscriptions and transactions. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Kagan/S&P Capital IQ, OMDIA, Box Office Mojo, DEG and Author estimates.

Stepping back, the relative stability of these figures surfaces two somewhat counterintuitive conclusions: 1) Given the growth of streaming and the resiliency of traditional pay TV (which, after all, still has over 70 million subscribers in the U.S.), it would be reasonable to assume that the whole video pie is growing or, alternatively, that consumers are shelling out more for video each month. 2) Similarly, for a long time, many equated the rise of streaming with the death of TV advertising. Neither is accurate.

Video Has Lost Share of Both Consumer and Advertiser “Wallets”

This point follows from the prior one. Although it might not seem so bad that consumer and advertiser video spend have been stable, that’s occurred even as both Personal Consumer Expenditures (PCE) and aggregate advertising spend (which tends to be closely correlated with Gross Domestic Product (GDP)) have both grown nominally (largely due to inflation). The result is that direct consumer spend on video as a proportion of PCE (Figure 7) and advertiser spend on video as a proportion of total advertising spending (Figure 8) have both declined in recent years.

Figure 7. Consumer Spending on Video Has Declined as a % of PCE…

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Kagan/S&P Capital IQ, OMDIA, Box Office Mojo, DEG and Author estimates.

Figure 8. …And Video Has Lost Share of Ad Budgets

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, MAGNA, MoffettNathanson, and Author estimates.

An interesting exercise is to figure out: how much bigger would the pie be if video kept pace (with both consumer and advertiser spend)? As shown, from 2019 to 2023, consumer video spend declined from roughly 1.0% to 0.8% of PCE and video advertising declined from 35% to 25% of total U.S. ad spend. If both figures stayed steady, it would’ve added about $45 billion to consumer spend and $39 billion to video advertising, or a whopping $84 billion combined. In other words, the total video business would be about 35% larger.

If consumer and advertiser spend on video kept pace with overall consumer and advertiser spending (respectively), it would’ve added 35% billion to the video pie!

Where Does the Money Go?

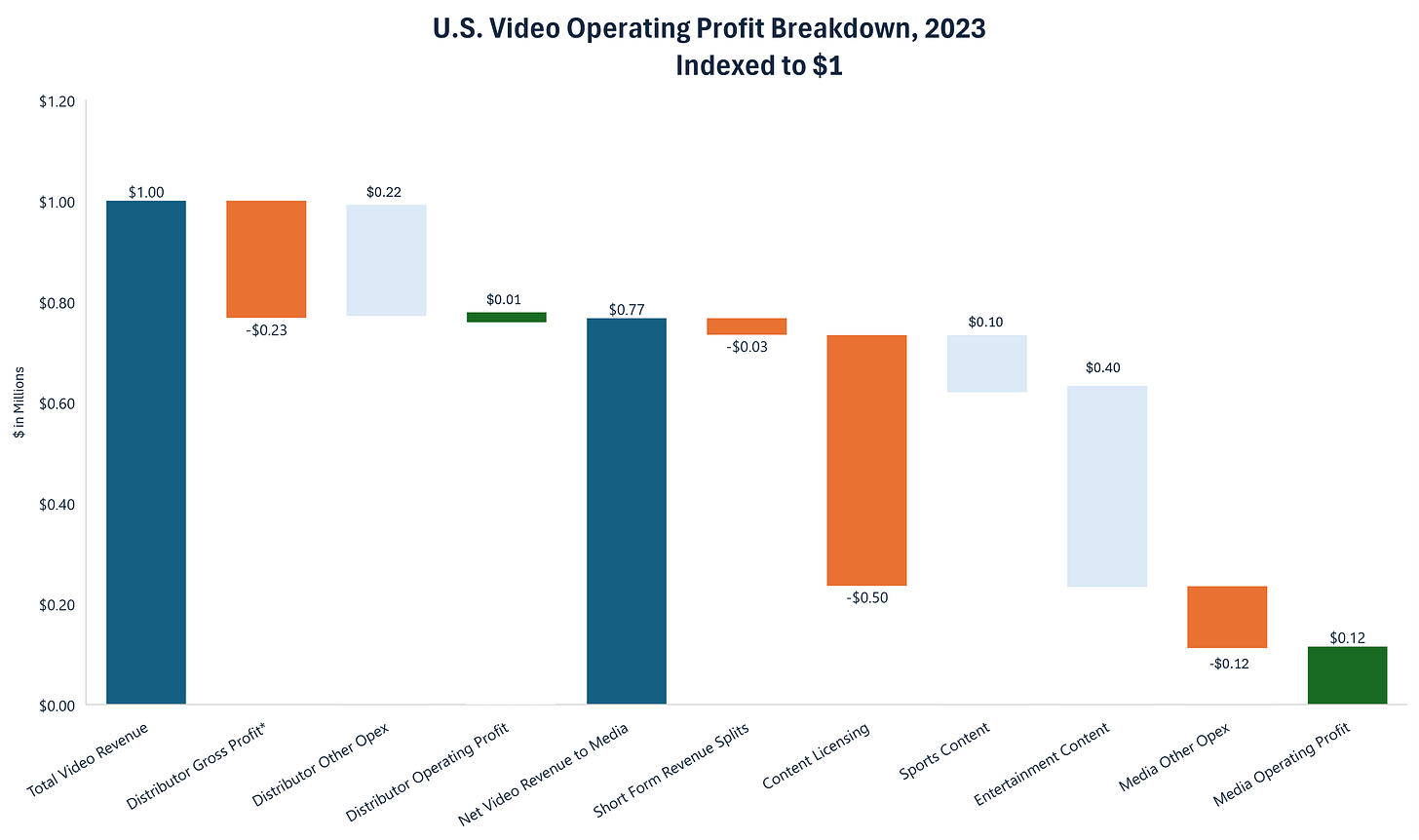

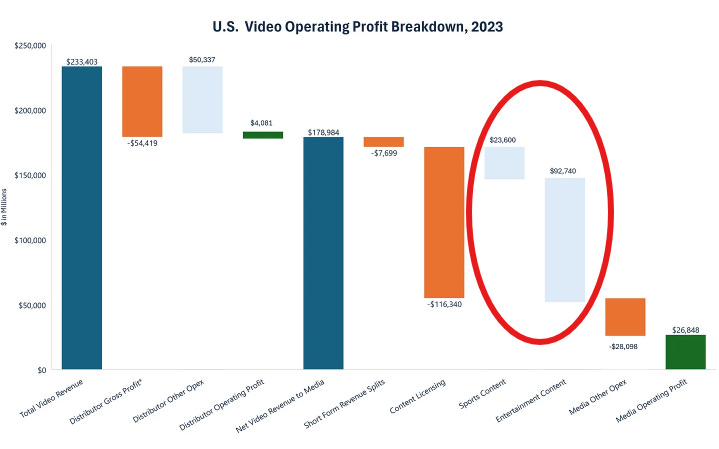

The next step in the analysis is to examine how this money is disbursed between distributors, content packagers/publishers and rights holders. This is shown in Figure 9 for 2023, again both the absolute dollars and indexed to $1.

This breakdown is less intuitive than the buildup in Figure 3, so let’s walk through how to interpret it:

The starting figure is total video revenue in 2023, which was the ending figure in Figure 3. Again, this is all the money spent by consumers and advertisers on traditional TV, streaming, YouTube advertising, theatrical movies and home entertainment in the U.S.

The next (orange) bar—”Distributor Gross Profit”—shows the revenue that was retained by distributors prior to their remittances to the content producers/packagers (Disney, WBD, NBCU, E.W. Scripps, etc.), or what might be called “media companies.” Distributors include pay TV providers (Comcast, DirecTV, YouTube TV), media buying agencies (GroupM, Publicis, Omnicom), movie theaters (AMC, Regal, Cinemark), digital distributors (Apple iTunes, Amazon Channels/Fire, Roku apps, Google Play, etc.) and retailers (Amazon, WalMart, Best Buy). Note that some companies have both resale and owned-and-operated businesses, so only the resale or distribution component is included here. (For instance, Roku acts as a reseller of streaming services and advertising inventory and also has owned-and-operated businesses, like The Roku Channel.) Note also that a significant amount of video is sold direct-to-consumer, like Netflix, Disney+, Hulu, Apple TV+, etc., so that isn’t captured here either.1 The subsequent two bars (light blue and green) disaggregate this gross profit between "Distributor Other Opex” and “Distributor Operating Profit.”

The next large blue bar (“Net Video Revenue to Media”) represents all the video revenue, both direct-to-consumer and wholesale, that was remitted to the companies that produce and package video content, like Disney, NBCU, Netflix, WarnerBros. Discovery, Netflix, YouTube (short form video, not YouTube TV), E.W. Scripps, Nextstar, Televisa, TEGNA, The Roku Channel, Amazon Prime, Apple TV+, etc., in the U.S. The next orange bar is the revenue split that YouTube paid creators and the subsequent orange bar shows all the money that media companies paid for content.

The next two light blue bars show how that content spend (producing and licensing) was distributed between sports and entertainment content last year.

The next (orange) bar shows how much media companies spent on non-content expenses (“Other Opex”) and, finally, the last bar is an estimate of how much they kept as operating profit.

Figure 9. Video Revenue Disbursement Between Distributors, Packagers/Publishers and Rights Holders

Note: *Distributors include pay TV distributors, theaters, local TV stations, media buying agencies, digital distributors (e.g., Apple and Amazon) and retailers. Source: Company reports, MoffettNathanson and Author estimates.

Distributors Don’t Keep A Lot

One relatively obvious observation here is that distributing video is not a great business. Comcast and Charter, for instance, report video gross margins in the mid-high 30% range, but after allocating other operating expenses to video, I estimate that operating margins fall in the mid single digits. Similarly, theaters and specialty retailers also operate roughly 5-10% operating margins. For every $1 spent on video in the U.S., distributors skim $0.23 off the top, but only keep about $0.01 as operating profit.

For Every $1 of Video Revenue, ~$0.50 is Spent on Content

It’s well understood that the big media companies spend a lot of money on content, but this analysis puts it in context. For each $1 that comes in, half goes toward producing and licensing content – money that is spent on talent, physical production, special effects, content licensing and sports rights. More on that in a moment.

For Big Media, the Big Problem is More $ Chasing a Fixed Revenue Pie

The big media companies are clearly struggling, especially as gauged by their stock prices. For instance, since the end of 2018, prior to their SVOD launches, PARA and WBD are down 75% and 71%, respectively, and DIS is flat. The S&P 500 has doubled over the same period.

This analysis reinforces, at least indirectly, that they have more of a cost problem than a revenue problem. Figure 10 shows total video revenue and EBITDA for the assets that currently constitute Disney, NBC Universal (a division of Comcast), Fox, Paramount and WarnerBros. Discovery in both 2018 and 2023 (i.e., for 2018, it includes CBS and Viacom, the predecessors to Paramount, and Warner Media and Discovery, the predecessors to WarnerBros. Discovery). It represents all video, including linear, streaming and studio, globally.

As shown, aggregate video revenue is up modestly over that period, about 1.5% per year, but video margins have fallen about 1,000 basis points, from 25% to 15%, and video EBITDA has declined by almost 40%. The chief challenge for the media companies is that they have been throwing more money at a stagnant revenue pie. These higher costs include substantial increases in content, marketing and operating expenses to support their streaming services.

Figure 10. For Big Media, Video Revenue is Flat, But Video Margins are Down a Lot

Notes: Represents global video revenue/EBITDA (including linear, streaming and studio). 2018 is the aggregate results of CBS, Discovery, Disney, Fox, NBCUniversal, Viacom and WarnerMedia. 2023 is the same assets included in 2018, reconstituted into Disney (now including most of the former Fox assets), “new” Fox, NBCUniversal, Paramount (the combination of CBS and Viacom) and WarnerBros. Discovery (the combination of Discovery and Warner Media). 2018 Disney results are pro forma the consolidation of Hulu for comparison purposes. Does not adjust for non-calendar fiscal years (Disney is September, Fox is June). Source: Company reports, Author estimates.

Is There a Sports Rights Bubble? Probably Not

In light of the pressure on traditional TV, recently a debate has sprung up whether or not there is a currently a sports rights bubble. The market for certain sports rights has tightened recently as both the largest traditional media companies and streamers like Amazon have reevaluated their cost structures. But the analysis above shows why the answer is probably not, especially for tier-1 sports.

There is no sign yet that media consolidation will reduce the number of sports bidders or that Amazon, Apple or Google will retreat from sports.

The Bidding Dynamic May Intensify, Not Lessen

Going forward, an important and largely unanalyzable factor will be the competitive bidding dynamic for sports rights. Obviously, if there is significant consolidation among traditional media companies or if Amazon, Apple and/or Google decide to pull in their horns, that might reduce the demand for sports rights and, consequently, rights fees.

For now, however, there are few signs of either happening. Despite frequent media and Wall Street speculation about “big media” consolidation (which has picked up lately following the two-year anniversary of the Discovery-WarnerMedia merger), it is very much unclear whether consolidation among traditional media companies will occur. It’s not obvious that any buyer wants to dramatically increase its exposure to linear TV assets or run the regulatory gauntlet. It’s worth noting that the only process that has been publicly confirmed is a proposed sale/merger of Paramount and, whether a transaction is consummated with Skydance or Apollo (or Apollo/Sony), it wouldn’t reduce the number of sports rights bidders.

The speculated Paramount transactions wouldn’t reduce the number of sports rights bidders.

Plus, there is reason to expect the “streamers” will increase their commitment to sports. Not surprisingly, Amazon, Apple and Google have all emerged as speculated bidders for NBA rights. Somewhat more surprisingly, so has Netflix. After swearing off live sports for years, it recently struck a 10-year deal, $5 billion deal, to carry WWE Raw. And, as Co-CEO Ted Sarandos said on Netflix’s recent 1Q earnings call, Netflix is “not anti-sports, but pro profitable growth.” More broadly, the recent push by Amazon and Netflix into advertising makes sports more economically viable for them. Since sports have built-in ad breaks, having established advertising operations puts them in a much better position to monetize the rights.

Content Budgets Will Likely Shift from Entertainment to Sports

Putting aside potential changes in the competitive bidding dynamic, there are several reasons to think that content budgets will continue to shift from entertainment to sports, supported in part by the analysis above:

There’s a lot of entertainment spend to be reallocated. As shown in Figure 11, last year spending on entertainment programming was 4x the spend on sports, or over $90 billion vs $24 billion.

Figure 11. Media Companies Spent an Estimated $90 Billion on Entertainment Content Last Year

Note: *Distributors include pay TV distributors, theaters, local TV stations, media buying agencies, digital distributors (e.g., Apple and Amazon) and retailers. Source: Company reports, MoffettNathanson and Author estimates.

Sports viewership is actually going up on traditional TV.

Sports viewing is dramatically outperforming entertainment programming. Perhaps the best way to show this empirically is with Figures 12 and 13, both of which come from MoffettNathanson, using Nielsen data. As shown in Figure 12, while aggregate TV (broadcast and cable) viewership has declined over the past four years, sports viewership has climbed 50% and its share of total viewing has almost doubled, from ~10% to 20%. Figure 13 shows that this viewing is broad based across age cohorts; while non-sports viewing has collapsed among younger demos, sports viewing has proved far more resilient.

Figure 12. Sports Programming Has Become Increasingly Important

Note: Percentage increases not calculable from chart due to rounding. Source: MoffettNathanson, using Nielsen data, Author estimates.

Figure 13. Sports Has Also Proved Far More Resilient Across Age Cohorts

Source: MoffettNathanson.

Not only is sports viewing growing, but that viewing monetizes far better. Figure 14 shows that, according to S&P Global, sports networks generate 3X the affiliate fee per hour of viewing relative to the next closest programming genre. Advertising CPMs are much higher too; according to Sportico, last year sports CPMs were about $75, vs. $42 for primetime broadcast. That gap probably continues to grow.

Figure 14. Sports Punches Way Above its Weight Generating Affiliate Fees

Source: S&P Global.

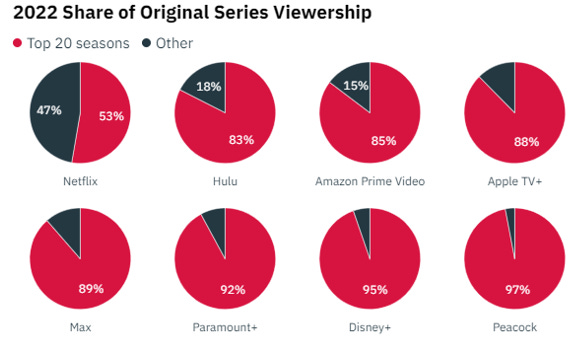

Entertainment programming has gotten riskier. I’ve discussed this in other posts, such as Power Laws in Culture, You Can’t Just Make the Hits and The Year(s) Ahead in Media - Concentration, but non-sports programming on TV is apparently becoming even more hit-driven. The reason is that, in a world of near-infinite choice, consumers are increasingly using popularity as a signal of quality. Popularity begets popularity in a powerful positive feedback loop, making the biggest hits bigger than ever. Figure 15 shows data recently released by Luminate illustrating that, for all the streamers other than Netflix, in 2022 the top 20 seasons represented nearly all their viewing. As a result of the rising importance of the biggest hits, the variance of returns in producing entertainment content, and therefore the risk, is also rising. Sports ratings vacillate year-to-year around storylines, star power, degree of competition, whether large or small market teams are winning, etc., but on TV today, sports is as close to a sure thing as you get.

While entertainment projects are increasingly a roll of the dice, sports are as close to a sure thing as you get.

Figure 15. For Streamers Other than Netflix, the Top Hits Represent Almost All Viewing

Source: Luminate, via Variety.

GenAI may ultimately reduce entertainment content costs. This is a longer-term phenomenon, but as I have written in other pieces (see AI Use Cases in Hollywood), GenAI holds the potential to significantly reduce the costs of producing entertainment content. This would also free up resources that could otherwise be allocated to sports.

As barriers to entry fall in creating entertainment, live events and sports will become relatively scarcer. As I have written many times, I believe that over time GenAI will blur the quality distinction between professionally-produced and independent/creator content and vastly increase the supply of entertainment content (for the most recent piece on this, see With Sora, AI Video Gets Ready for its Close Up). Value always flows to relative scarcity. In an environment of abundant quality entertainment content, live events, like sports, will become relatively scarcer.

Another Perspective on the Video Transition

The video business has obviously undergone a significant transition in the last decade, as consumers, providers and advertisers embraced streaming. As shown above (Figure 4), streaming is in the process of displacing and, to some degree, replacing traditional pay TV, broadcast, home video and theatrical.

I believe that the video business is on the verge of another major transition, as GenAI reduces the barriers to high quality content video content creation, exacerbating another low-end disruption that is already underway. (Besides With Sora, AI Video Gets Ready for its Close Up, see Forget Peak TV, Here Comes Infinite TV, How Will the “Disruption” of Hollywood Play Out?, AI Use Cases in Hollywood and Is GenAI a Sustaining or Disruptive Innovation in Hollywood?) Put differently, just as the last decade in TV and film was defined by the disruption of content distribution, the next decade may be defined by the disruption of content creation.

This idea, and the uncertainty around it, is very unsettling to Hollywood. The analysis above, however, strikes a somewhat hopeful note. Despite the perception of radical change in the video business, pay TV is still the lion’s share of video revenue more than a decade into the last disruption. Plus, both consumer and advertiser expenditures on video—while losing share of spend—have at least remained nominally stable.

“Following the money” shows that sometimes things aren’t changing as radically as we think they are.

However, many D2C services are sold through third party distributors, like Amazon Channels, which I have attempted to capture in “Distributors’ Gross Profit.”

Fantastic piece. The more things change... And sports underweight.

Great job on looking that up! Super interesting!